EP 3 607 651 A1 relates to Control electronics for refrigeration systems. It stems from the PCT application PCT/EP2018/056793 published as WO 2019/015812.

Brief outline of the case

The application was refused for lack of IS of all the requests on file, and the applicant appealed.

The board confirmed the refusal, but for lack of clarity.

The board’s communication under Art 15(1) RPBA

In a communication pursuant to Art 15(1) RPBA attached to the summons to OP, the board informed the applicant of its preliminary view that, before examining IS, it would first have to discuss the clarity of claim 1, cf. Art 84.

The Board expressed detailed concerns about the clarity of various terms and structural features, including ‘commutation electronics’.

The Board further noted that it was not obliged to interpret an unclear claim by making assumptions and that an examination under Art 56 could not be carried out on that basis.

The board’s decision

The board held that the term ‘commutation electronics’ in claim 1 of the MR is so vague that it does not meet the clarity requirement of Art 84.

The claim contains neither structural nor functional features that would enable a skilled person to recognise what is meant by ‘commutation electronics’ and which embodiments are to be covered by this term.

Nor can any clear technical teaching with regard to ‘commutation electronics’ be derived from the context of the claimed subject-matter. In addition, neither the description nor the figures provide a technical definition or generally accepted specification of this term.

The board was convinced that ‘commutation electronics’ is not an established technical term with a clear meaning in the relevant technical field of control electronics for refrigeration systems.

In particular, a skilled person would not understand from its CGK that the ‘commutation electronics’ within the meaning of claim 1 is to be understood as EC commutation electronics, i.e. EC = electronic commutation, for an electronically commutated motor.

Neither the term ‘EC commutation electronics’ nor ‘EC motor’ is disclosed anywhere in the application. Nor are there any other indications that would immediately make it clear to a skilled person, in the course of a normal, reasonable reading, that the ‘commutation electronics’ referred to in claim 1 are to be understood as EC commutation electronics.

Even if this were assumed in favour of the applicant, it would remain unclear whether, without further explanation in the application, the term should be understood in a narrow sense, only power commutation, i.e. inverters with gate drivers, or in a broad sense, complete drive electronics including drivers, control, sensors, protection and interfaces.

Skilled persons are familiar with at least two fundamentally different types of commutation electronics: on the one hand, the power-carrying circuit component, e.g. DC/AC converter, which switches currents and physically effects commutation, and on the other hand, the control level consisting of control/sensor technology and logic, which specifies the timing and function of commutation.

The varying interpretations presented by the applicant in the proceedings, firstly the power section, later the control electronics, demonstrate this objective ambiguity.

For the sake of completeness, the board noted that the breadth of the term might not be detrimental if there were a recognised, clearly defined technical meaning or if the application itself provided a technical definition or implementation details that supported the broad term claimed.

However, it is precisely this clarity that is lacking here. The skilled person would thus be forced to develop their own specifications in order to determine the limits of the subject matter of the claim, which undermines the necessary legal certainty of the claim limits.

The contested decision already recognised the lack of clear technical meaning and the lack of a defining disclosure of the term in question as a problem of clarity, even though this aspect was not used as an independent ground for refusal. The ED decided lack of IS separately for both possible interpretation of ‘commutation electronics’, the power-carrying circuit component one the one hand, and complete drive electronics on the other hand.

The board did not agree with the ED’s approach in this respect, since no substantive objection as to clarity was raised despite the recognised considerable conceptual vagueness.

In view of the obligation to examine under Art 94(1) and the importance of clarity for the distinctiveness of the claimed subject-matter, see Guidelines F-IV, 4.1 and of G 1/24, OJ EPO 2025, A60, reasons 20, a final assessment should and must have been made already in the proceedings before the ED.

Comments

In the presence of a severe lack of clarity, the board made clear, that a lack of clarity can be an obstacle on deciding upon N and IS of the subject-matter of a claim.

Rather than deciding on IS with two possible interpretations, the ED should have refused the application for lack of clarity.

Reasons 20 of G 1/24 read:

“The above considerations highlight the importance of the ED carrying out a high quality examination of whether a claim fulfils the clarity requirements of Art 84. The correct response to any unclarity in a claim is amendment. This approach was emphasised in the Comments of the President of the EPO”.

We can expect boards quoting regularly Reasons 20 of G 1/24. This was already the case in T 866/24, commented in the present blog.

The board’s comment, that it was not obliged to interpret an unclear claim by making assumptions is equivalent to the statement of the board in T 2027/23, commented in the present blog, that a board is not prepared to carry out interpretative summersaults when examining a claim G 1/24, see Catchword .

Comments

10 replies on “T 389/24-Lack of clarity and G 1/24”

Reading your write-up, Daniel, reminds me of a detail of the law of patentability in the USA, namely when a claim has to be found invalid because it is “indefinite”. More or less, it is the same as “lacking clarity”.

Just like “clarity” the concept of “definiteness” has a sliding scale from zero to 100%, with nearly all cases of indefiniteness (or lack of clarity) lying somewhere in between the ends of the scale. So the US courts came up with a test of what is truly “indefinite” namely “insolubly ambiguous”. From what you write, the term “commutation electronics” in the claim, with no help from the description to resolve the ambiguity, looks to me like a case of invalidity through indefiniteness.

Pity the UPC court, faced with an insolubly ambiguous claim, and no means to strike it down for lack of clarity. Solution: give the claim its narrow meaning for judging infringement but its wide meaning for assessing its validity.

Dear Max Drei,

Your comment is very interesting. The present case is indeed belonging to the category “insolubly ambiguous” as defined in the USA.

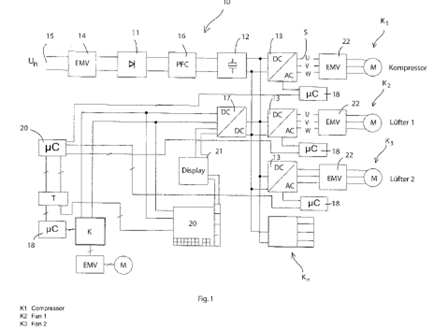

When you look at the drawing, there are a few blocks which could be understood as being riddled with ‘commutation electronics’. You have DC/DC and DC/AC converters as well as a control circuit K which can also be considered as comprising “commutation electronics”. This is exactly what the BA has queried.

The representative has actually taken over the proprietary jargon of the applicant without realising that it had no generally accepted meaning.

In the present case the application has been refused, but I dare think how an opponent or a OD could deal with such a claim. Not only a court would thus have difficulties with such a claim.

The reminder to G 1/24 in the decision should be taken to hart by EDs and ODs.

In such a case, the claim ought to be interpreted as precisely as possible in view of the description to come then to the conclusion that it lacks IS.

This is what the ED has tried to do, but it has to be agreed with the board that in the present situation in examination, the clarity objection is overriding.

Indeed Sometimes being an examiner is hard. I guess it’s easier to tell an applicant that the claim fails under 54 or 55 than it is to tell them that their claim is so lacking in clarity that their application must be refused.

Dear Max Drei,

I fully agree with your comment.

Experience shows that, during examination, a mere objection of lack of clarity is often less efficient as it might end in endless discussions. In this respect, it is better to interpret the claim in spite of the lack of clarity, and based on this interpretation object a lack of novelty and inventive step. This is the only way to make the applicant move.

I have practiced this as examiner and it was the advice I later gave to the examiners I was in charge of. This explains the OD’s way of handling the case, although in view of the blatant lack of clarity a lack of clarity should have been enough.

Two points:

1) Typing error. I did indeed intend “56” but it came out as “55”. Sorry about that.

2) I remember the days when Americans designated the EPO as IPEA and got upset when an EPO examinier told them that their claim was not clear. Much more effective with US attorneys is to construe the unclear claim broadly and tell them that their claim is not distinct from the prior art references.

Purposefully naive question: when the independent claim is insolubly ambiguous, why can’t the patent be revoked for insufficiency of disclosure? After all, if the skilled person cannot figure out what the claimed invention is, then they cannot reproduce it.

@ Extraneous Attorney,

The question is not naïve at all. I thought for a moment the same, but when looking at the Fig., I would think that an electronic engineer can make head and tail with the information as DC/DC or DC/AC converters and all other components like μC, EMV filters, motors, display etc, can be bought off the shelf, in order to be put together and have the system working.

The problem here is the claim formulation as under “commutation electronics”, two very distinct aspects are meant, the commutation electronics for the motors as well as well as the commutation electronics for the actual control.

When reading the problem the applicant wanted to solve, what was actually claimed appears miles away.

You wrote ‘I would think that an electronic engineer can make head and tail with the information as DC/DC or DC/AC converters and all other components like μC, EMV filters, motors, display etc, can be bought off the shelf, in order to be put together and have the system working. ‘

This is probably correct, but is it decisive?

The reasoning can also be: OK, the skilled person can build a certain system. But (s)he has no idea then whether this certain system is actually a system according to the claims or not (due to the clarity problem).

In other words, it is fundamentally impossible for the skilled person to determine whether (s)he has carried out the claimed invention. This means in turn that the legal evaluation of sufficiency of disclosure is fundamentally impossible to perform (and therefore that Art 83 is not complied with).

@ BJ

Thanks for your comment.

The answer is decisive as far as Art 83 is concerned. What is at stake here is the fact that the claim is unclear.

There is often a delicate balance to make between Art 83 and Art 84. It is thus well possible to have situations in which both objections have to be raised at the same time. In this respect your conclusion is correct for specific situations.

In the present case, the situation is not as intricate. In view of the diagram the skilled person is most probably in the position of reproducing the circuit disclosed therein.

The problem is that the wording of the claim is ambiguous to the point that it covers two different possibilities having a totally different meaning: commutation for the motors or commutation within the control device.

In T 1608/13, Reasons 3.3. last §, the board held that a potential lack of clarity would not deprive the skilled person of the promise of the invention, and would not result in insufficiency of disclosure.

This is the case here, the lack of clarity of the claim does not hinder the skilled person to implement the disclosed circuitry

As to the interplay between Art 83, 84 and 56, I refer to the catchword of T 2001/12.

@BJ @Daniel X. Thomas

Thank you both for your clarifications.