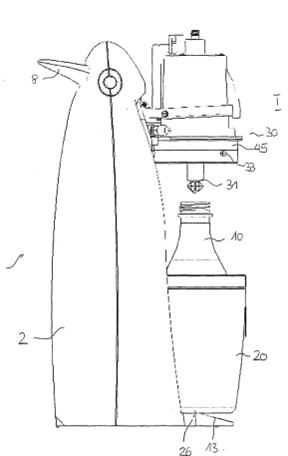

EP 1 793 917 B1 relates to a well-known device for carbonating water in which the bottle is received in a container=flask whereby the container and the filling head are movable in relation to each other between an insertion position (I) and a carbonating position (C).

Brief outline of the case

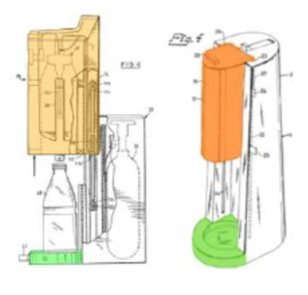

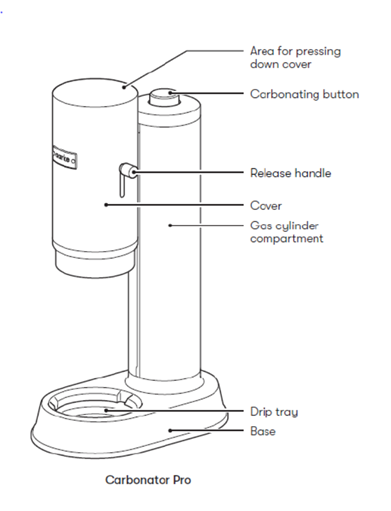

The patent in suit has been granted with effect for Austria, Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, Italy and Sweden. The proprietor alleged infringement in view of the device represented here:

The points in dispute relate to the following features:

- “receiving flask”, i.e. container for receiving a water bottle

- flask and filling head moveable in relation to each other between insertion and carbonating position, i.e. the filling head moves away linearly

- “in the insertion position the filling head is spaced away from the receiving flask such that said container can be placed into said flask“, for instance the container swivels what allows insertion of the bottle

- „the filling head and the receiving flask are provided with locking means for interlocking connection there between, preferably with a bayonet connection“, i.e. the filing head and the flask are aligned towards each other and are locked together.

The LD consdered the patent infringed and ordered the infringer to pay damages going back to 20.02.2010 which is one month after the granting date. The filing date is 23.08.2005, i.e the patent will expire in less thana year.

The prior art

In the prior art it had been suggested to provide a carbonating device with a burst protection shield for the liquid container and with a mechanism for forming a sealing connection between a carbonating head and the container without the need of screwing the bottle into the carbonating head.

However, the shield which comes over the bottle, upon the occurrence of a burst bottle, may be lifted upwardly thus opening a gap between the lower end of the shield and the stand of the machine onto which the bottle is placed. Through this gap, glass particles, which are not contained by the protective shield, are likely to be released and injure the user.

Interpretation of the claim

The LD referred first to a series of decisions of the UPC and especially from the CoA and of the CD Munich. They all, as well as the LD refer to Art 69(1) UPC and Art 1 of the Protocol.

For the LD, the claim must not be limited to the scope of preferred embodiments. The scope of a claim extends to subject-matter that the skilled person understands as the patentee’s claim after interpretation using the description and drawings. A claim interpretation which is supported by the description and drawings as a whole is generally not limited by a drawing showing only a specific shape of a component.

For the LD, the flask fulfils two main technical functions:

- receiving a bottle containing liquid and

- forming a substantially securely closed cavity in cooperation with the filling head when interlockingly connected to the filling head

The general description does not prescribe a specific height for the flask which is mandatory to receive a glass bottle and to fulfil its protective function. The skilled person understands that the receiving flask may need a certain height in relation to the bottle to contain respectively enclose it. But this is not necessary if the flask only needs to receive it and keep it in place. The latter is sufficient according to the claim.

The second function of providing burst protection is not achieved solely by the flask itself but always in connection with the filling head and the locking means. Neither claim 1 nor the general description demand a certain amount of contribution to the burst protection as long as the (overall) burst protection is efficient.

The prior art documents only provide bases where the liquid container can be but on but no separate structure into which the liquid container can be placed and which contributes to burst protection.

A substantially closed cavity serves the main purpose to protect the user from flying glass particles in an uncontrolled manner. Compared to the prior art, the disclosed structure avoids that a burst can cause an opening gap of the substantially closed cavity.

The wording of the claim requires a moveability of either receiving flask or the filling head or both of them. It does not mean that both have to move relative to each other; it is sufficient if the movement is such that the bottle can be inserted. That the flask is tilting in order to allow insertion is only one possibility subject-matter of dependent claims.

For the LD, any interlocking connection that is achieved by locking means of the filling head and the receiving flask is covered by the patent, and only preferably it is a bayonet connection. The “interlocking connection” is part of overcoming what has been identified as a drawback of the prior art, namely that the locking mechanisms locking the shield to the body of the machine may not be sufficiently strong to protect the components of the carbonating device, in particular in the event of an empty bottle failure. The skilled person will understand that an “interlocking connection” must be “direct”, “in axial direction” and of a nature to allow the formation of a substantial closed cavity.

The infringing device

According to the LD, the device comprises a flask for receiving liquid container meaning a glass bottle.

According to the LD´s interpretation, the specific height of the receiving flask is not crucial as long as the flask is able to receive a bottle.

The filling head and the flask are in contact with each other to form a substantially closed cavity. It is undisputed that the challenged embodiment clearly offers burst protection.

The device of the defendants is thus infringing.

The Gilette defence of the infringer

The defendant argued that the claim construction cannot be so broad as to cover the prior art corresponding to the base and movable cover forming the burst protection in the prior art. This defence does not entail a comparison between the patent in suit and the prior art but instead, it entails a comparison between the challenged embodiment and the prior art.

The LD dismissed the argument as in Art 69(1) EPC there is no question of prior art. Only the claims have to be considered and interpreted in the light of the description and the drawings.

Comments

It can be expected that the case will go to appeal, and it will hinge on how the CoA will interpret the feature “flask”.

I am personally not convinced that there is an infringement. It is clear that in view of the prior art, a mere linear movement in order to separate the flask from the filling head was anticipated and the idea of the pivoting of the flask in oder to allow insertion nearly imposed itself. The claim has been drafted more broadly, and since there were only A documents in the ISR establihed by the EPO, patentability has never been discussed in examination.

One problem for the infringer is the fact that it owed that its construction was devised in order to circumvent the patent. Another problem of the infringer is that it brought new arguments in defence too late, thereby ignoring the front-loaded nature of the UPC proceedings.

A Gilette defence is possible defence in the UK, but it is not sure that it will ever cross the Channel.

Lenght of the period for which damages are due

The LD also ordered the infringer to provide the claimant with information on the extent to which they have committed the infringement since 20.01.2010. This date is the date of grant of the patent. The infringer has to compensate the claimant for all damage that the latter has suffered and will continue to suffer carried out since 20.02. 2010.

Art 72 UPCA

It is worth noting that filing date of the patent is 23.08.2005, that means the patent will lapse within a few months. This is a such not a reason for not claiming infringement.

I wonder in how far the order for compensation is compatible with Art 72 UPCA according to which actions relating to all forms of financial compensation may not be brought more than five years after the date on which the applicant became aware, or had reasonable grounds to become aware, of the last fact justifying the action.

The patent having been granted in 2010 and the action in infringement been launched in the last years of the patent, the limitation period for financial compensation actions being five years, the proprietor appears to have tolerated the infringement for many years. Is it therefore reasonable that damages are calculated from the granting date of the patent?

Retroactive effect of the UPC to the advantage of a claimant

The LD’s decision and a possible decision of the CoA confirming the infringement raises a question which is possibly more of legal policy than of strict legal nature.

Up to the creation of the UPC, the proprietor could only act separately for infringement in the EPC member states in which the patent was validated.

With the creation of the UPC, a potential infringer can be sued in a court with a much wider territorial jurisdiction and with much higher costs, especially costs for representation.

It is doubtful that such a retroactive change of position to the detriment of a potential infringer but to the exclusive advantage, and only within the realm of the proprietor, is at all acceptable. This is the more so since the infringement has apparently been tolerated for a very long time.

When the various parliaments ratified the UPCA, it is doubtful that they were properly informed of this problem.

As the decision should be enforced in France, it would be interesting if the infringer could and would file a priority question of constitutionality (QPC, Question Prioritaire de Constitutionalité).

Comments

5 replies on “LD Düsseldorf – UPC_CFI_373/2023 – Infringement action at the end of a patent’s life – Art 72 UPCA”

“The Court understands Defendant’s argument to mean that the claim construction cannot be so broad as to cover the prior art corresponding to the base and movable cover forming the burst protection in the 1982 patent. In particular, Defendant argues that its defence does not entail a comparison between the patent in suit and the patent 1982 but instead, it entails a comparison between the challenged embodiment and the prior art. In this context, it is important to acknowledge that, pursuant to Art. 69(1) S. 1 EPC, the extent of the protection conferred by a European Patent shall be determined by the claims. It is therefore the claim that defines the outer limit of the scope of protection. Nevertheless, the description and the drawings shall be used to interpret the claims. Prior art is not mentioned there.”

This is not an accurate characterization of the Gillette-Defence. The Gillette-Defence is not a method of claim interpretation using the prior art. The clue is in the name: it is a defence when accused of infringement. If the alleged infringing article replicates the prior art, there is no need to look at the patent or interpret its claims, because no patent could simultaneously be valid over the prior art while capturing the alleged infringement. If the same interpretation is applied for infringement and novelty, the Gillette-Defence is an inevitable corollary, so there is room for a Gillette-Defence at the UPC. The Gillette-Defence was either not argued correctly or misunderstood by the court.

@Anonymous

I fully agree with you, the Gillette defence is just common sense and the court applies Art 69 in a way which is contrary to common sense. It seems to be based on a confusion between claim interpretation under Art 69 and the doctrine of equivalents according to its protocol.

The Gillette defence has been adopted in Germany in 1986 in the form of the German Formstein defence, but the Formstein defence goes way farther than the Gillette defence since it holds that an embodiment cannot infringe a claim under the doctrine of equivalents if it is obvious over the prior art.

It is of note that both the Gillette and Formstein defences were endorsed by AIPPI in 2023 in its World Congress in Istanbul, reflecting a consensus at international level among IP practitioners. Point 6 of the AIPPI Q284 resolution reads as follows :

“ An embodiment cannot infringe a claim under the doctrine of equivalents if the embodiment is disclosed in the prior art or is obvious over the prior art.”

The decision of the LD Dusseldorf is interesting though as a showing of independence vis-à-vis the case law of Germany. It is a very important matter of principle for the UPC. Let’s wait now for a decision of the UPC court of appeal on the matter.

@Mr Thomas

Many thanks for your detailed report and analysis.

@ Anonymous of 06.11.24 and Mr Hagel.

Thanks for both your comments.

I am fully aware of the Gilette, respectively Formstein, defence in case of infringement. I wanted to show that the alleged infringer has tried this way in defence, without deciding whether the Gilette defence was correct or not.

The dismissal of the Gilette defence with reference to Art 69 is certainly possible, but here we will indeed have to see what the CoA UPC will be saying.

On the other hand, when the CoA has repeatedly decided that, before any decision, the claim has always to be interpreted taking into account the description or the drawings, it has well adopted German case law on a point much more relevant than the Gilette or Formstein defence.

At a seminar on the UPC in Strasbourg the question was rightly raised whether the UPC will be a true international court (Esperanto court) or a German court with international decorations. The question is still open.

As to the “Gillette Defence”, I write to support the comment of Anonymous and to ask whether Anonymous is right, that either the Defence did not plead in line with the Defence or the court did not understand the defence.

And another thing. Why shouldn’t the Gillette defence cross the water between the UK and the European mainland? After all, if the accused embodiment replicates the prior art then surely the infringement action must fail, oder? Either the asserted claim lacks novelty, or it fails to catch the accused embodiment within its scope of protection, or both. There is, in pure logic, and without any need to construe the claim, zero room for a court to enjoin an accused party for infringing the exclusive rights given by the Patent Office when it grants the patent. That’s the intellectual and practical beauty of the Gillette Defence, isn’t it?

Dear Max Drei,

As far as the Gilette defence is concerned, I tried to reproduce what the CFI said. Whether the CFI understood or not the Gilette defence is not really relevant. It remains that the CFI did clearly not want to go into it. It stuck to Art 69 and the Protocol.

I have nothing against the Gilette defence. It is indeed very simple and convincing. Having been devised in the UK and the UK, firstly being a country applying common law, and secondly having left the EU, where two reasons why I thought that it might not cross The Channel.

The situation is different with the Formstein defence as it originates at the BGH, and conversely has not reached the UK although it has been envisaged to be used there. Formstein defence is a kind of Gilette defence applied to equivalents.

Be it Gilette or Formstein, both defences allow to circumvent the application of Art 69 and of the protocol. This can explain the reservations of the UPC and of other courts.

As far as infringement by equivalents is concrned, we are far at the UPC of a line of case law, first defining equivalents, and then applying the definition to actual cases. Art 2 of the Protocol mentions equivalents, without however defining them. At the Diplomatic Conference in 2000, the EPO proposed a defintion of equivalents in an Art 3 of the Protocol. Art 3 was turned down by the member states.