The patent relates to the use of hot-melt adhesive for the collation of containers and bottles for beverages or food into shelf ready packs of various items.

Brief outline of the case

The opponent appealed the rejection of the opposition.

In its communication under Art 15(1) RPBA21, the board expressed the opinion that claim 1 as granted lacked IS over D1=US5331038, a document not found in ESR.

During OP, the MR, rejection of the opposition and AR1 were withdrawn. The proprietor only maintained AR2.

The board decided maintenance on the basis of AR2.

The subject-matter of claim 1 of AR 2 differs from claim 1 of the patent as granted in that the following feature has been introduced into claim 1:

“wherein the hot-melt adhesive compound has a density of between 0.790 – 1.2 g/cm**(3), a melt flow index of 15 – 4000 g/min (@200°C), a Brookfield viscosity @ 160°C between 200 and 10,000 cPs, a Shore hardness in the range of 15 and 70 A at 23°C according to ASTM D2240, and a softening point determined by ASTM E28 above 40°C and not greater than 158°C“.

As the feature newly introduced into claim 1 is disclosed on page 3, third line from the bottom, to page 4, line 2, of the application as filed, the board considered that there were no infringement of Art 123(2).

The late objection of lack of sufficiency from the opponent was not considered convincing by the board as there are no verifiable facts on file which could raise serious doubts that the invention can be carried out. Late filed experimental data where not admitted by the board.

The mere absence of an example in the patent that tests the specific use defined in claim 1 cannot raise serious doubts that the invention can be carried out and does not lead to the burden of proof being shifted, either. Under these circumstances, the burden of proof remains with the opponent.

There are however serious doubts about the validity of the claim as the measurement methods of some parameters are not properly defined.

Features in brackets in the claim

The measurement temperature of the melt flow index is only mentioned in brackets in the claim: (@200°C).

In T 1481/05, Reasons 3.4-3.5, it was held that “the use of parentheses by itself introduces some level of ambiguity in any text, patent claims being no exception. Therefore, as a rule, the use of parentheses in claims should be avoided, apart from the well-established use with reference signs or their standard uses in the relevant technology”.

As the expression was taken from the description, the corresponding ambiguity should have been tackled under G 3/14. It was easy to correct, deleting the parentheses, but this would not have been enough to save the patent.

Melt flow index

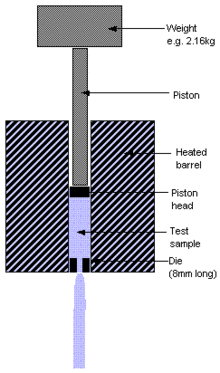

The Melt Flow Index (MFI) is a measure of the ease of flow of the melt of a thermoplastic polymer. It is defined as the mass of polymer, in grams, flowing in ten minutes through a capillary of a specific diameter and length by a pressure applied via prescribed alternative gravimetric weights for alternative prescribed temperatures.

In principle, ISO standard 1133-1/2011 governs the procedure for measurement of the melt flow index.

There is no definition as to how the melt flow index as indicated in the claim can be measured. What is missing is at least the diameter and the length of the die through which the polymer is expelled.

As the necessary indications are missing in the claim and in the description, the only conclusion is a clear lack of sufficiency.

Brookfiled viscosimeter

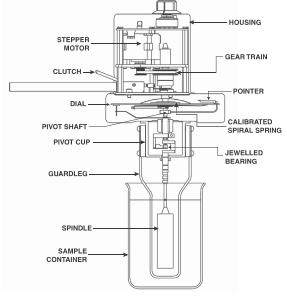

Classical Brookfield viscometers employ the principle of rotational viscometry—the torque required to turn an object, such as a spindle, in a fluid indicates the viscosity of the fluid.

The amount of viscous drag is proportional to the amount of torque required to rotate the spindle, and thus to the viscosity of a Newtonian fluid. In the case of non-Newtonian fluids, Brookfield viscosities measured under the same conditions (model, spindle, speed, temperature, time of test, container, and any other sample preparation procedures that may affect the behaviour of the fluid) can be compared.

According to a document published by the manufacturer of Brookfield viscosimeters, the following information should always be recorded when making a viscosity measurement: viscometer model, spindle (or accessory), rotational speed, container size or dimensions, sample temperature, time of spindle rotation, sample preparation procedure (if any), and whether or not the spindle guard leg was used. See D1 in T 808/09.

D1 in T 808/09 teaches the person skilled in the art the essential parameters which have to be considered when performing viscosity measurement using a Brookfield viscosimeter.

In the present case, the only elements found in the description and in the claim is that a Brookfield viscosimeter is to be used at 160°C. Without the indication of the type of viscosimeter and of the further necessary parameters, a measure of viscosity cannot be properly carried out. With polymers, i.e. non-Newtonian fluids par excellence, the viscosity changes during the polymerisation process, the time of test is also an important factor.

In T 808/09, in the absence of all the necessary parameters, even when using a Brookfield viscosimeter, the board decided that the invention was not sufficiently disclosed.

As the necessary indications are missing in the claim and in the description, the only conclusion is a clear lack of sufficiency.

Softening point determination

The softening point is to be measured according to ASTM E28. There is a new version of the norm issued in 2022. This means that there must be earlier versions of this norm as ASTM adopted for the first time a test method in 1916.

As the date of the norm is not indicated, it is not possible to determine the version of the norm to take into account.

As the necessary indications are missing in the claim and in the description, the only conclusion is a clear lack of sufficiency.

Comments

One has to be aware that norms are not fixed in time, but they can evolve in view of developments of technology. Some become obsolete and new ones are created, or even their content may vary with time.

In T 881/02 the discussion was inter alia about the norm “ASTM D 5209-91” whilst it existed also a norm “ASTM D 5209-92” before the priority date. The proprietor argued in vain that “in accordance with the ASTM D-5209” in the granted claims and the expression in “accordance with ASTM D 5209-91” in the claims of both AR boiled down to the same.

In T 783/05, the patent relates to a method for marking of a fibre product with a laser. The originally filed description contained a reference to DIN 4102A (Non flammability) for construction material. A copy of the front page of DIN 4102 A was only filed during opposition. This copy of DIN 4102A bears a publication date of May 1981. The board held that claim 1 of AR2 was unclear as it was made reference to a norm standard of which the date is unknown.

In the present case, since the statement added to the claim was taken from the description, G 3/14 could have been applied. Since the designation of the norm and the specification of the spindle in the Brookfield viscosimeter could not be added into the description, the objection was more likely to be an objection under Art 83 which cannot be overcome without infringing Art 123(2).

Since the various measurement methods are not properly defined, it is possible to consider that, independently of the late submissions by the opponent of experimental data which were not admitted, the latter was actually not in a position to submit verifiable facts, and that the opponent’s insufficiency objection was not based on unsubstantiated assertions which cannot raise serious doubts that the invention can be carried out.

On the procedure

It appears that claim 1 should not have been granted as the original search did not find D1=US5331038.

The patent bears the IPC classes B29C65/48; C08J5/12; C09J125/08; C09J131/04; C09J133/08; C09J153/02; B29L31/00.

D1 bears the IPC classes C09J151/00; C09J153/00; (IPC1-7): C08F8/04; C08L51/00; C08L53/00. As the search was carried out in C09J, cf. the ESR, there is no apparent reason for not finding D1.

Actually, in view of the above observations on the measurement methods, the ED should have required the deletion of the corresponding § of the description before grant. The objection could have been a combined objection under Art 83/84.

The OD rejected the opposition, but the board decided maintenance in amended form on the basis of AR2. This decision is thus one more of the 50+% of decisions of ODs set aside by a BA.

On the other hand, the validity of claim 1 as maintained is, in view of the above consideration about the measuring methods, seriously in doubt. In the present case, the onus of proof should actually have been shifted to the proprietor.

https://www.epo.org/en/boards-of-appeal/decisions/t211011eu1

Comments

6 replies on “T 1011/21 – Some problems with the claim as maintained – Is sufficiency really given?”

Daniel, I am intrigued by your last paragraph.

Is the job of the appeal instance to (A) adjudicate between the parties and to decide on the merits of the appeal, setting aside any unfortunate end results such as not revoking a patent that seems to be invalid?

Or is the Board’s duty (B) to the public, to filter out patents that are revealed to be invalid even when the Opponent itself has failed to construct in due time a case for revoking the patent?

It seems to me that for the sake of legal certainty and orderly handling of opposition proceedings on appeal, the judicial instance, the appeal instance, should favour A over B. Different, I think, in administrative proceedings before the OD, where the Examiners have more discretion to go rooting into the case.

From your last paragraph, I’m not sure that you agree with me on that.

Dear Max Drei,

Thanks for your comment.

Taking your both alternatives (A) and (B) into account, I would say that it should be a bit of both.

In opposition, and opposition appeal the aim of the EPO is not to maintain patents which should not be maintained as they manifestly correspond to the revocation criterion under Art 100 and 101(2). There is always a silent player present in opposition: the public, even if the opposition procedure is triggered by a third party which considers the grant unjustified. The EPO and the boards of appeal are not there to be kind to patent proprietors as it is for instance the case at the German Federal Court (BGH). This is for part (B).

Within the context of (B), the job of the appeal instance to (A) is, in my opinion, to adjudicate between the parties and to decide on the merits of the appeal, setting aside any unfortunate end results. In the present case, the ground of opposition under Art 100(b) was present and properly substantiated from the beginning of the opposition. The new arguments brought forward by the opponent were not admitted for purely formal reasons as they were filed late. On the other hand, it was manifest that the claim maintained by the board could not be enabled, and the only sensible decision would have been to revoke the patent.

I would also add, that should the search have been properly carried out, we would not have been in the situation in which we ended.

I would be curious to see if the proprietor will be able to enforce his amended patent in the countries in which it was validated. But as a patent representative said to me in 1974: in front of a court you are like on high see, you are in the hands of god.

I was under the opinion that the Boards had moved away from considering a lack of recital of the precise measurement conditions to be objectionable under sufficiency, with the current view being that it is to be considered a lack of clarity, which of course is not a ground for opposition.

Dear Kant,

Thanks for your comment.

The case law is rather divided when it comes, in opposition appeal, to the absence of a measurement method and sufficiency or clarity,

I would go as far as to claim that if a board does not want to be too bothered, it goes for clarity and if G 3/14 is not applicable, then the matter is easily settled for the board.

Under clarity rather than sufficiency, the following decisions can be quoted as examples: T 250/15, T 1255/14 or T 2700/17.

Under sufficiency and not clarity, the following decisions can be quoted as examples: T 1845/14, T 1188/15 or T 2341/17.

In order to see whether an objection should be raised under Art 83 or Art 84, I consider in first instance that an objection under Art 83 is applicable when there is no method at all in the original disclosure, or if common general knowledge does fill the gap in information. In order to overcome the objection of sufficiency, it is in general necessary to add matter to the original specification. This is manifestly a no go. The duality Art 83-123(2) is a very good help when discriminating between Art 83 and 84.

If a method is disclosed in the original disclosure, then clarity applies, as it can be considered that an essential feature is not present in the claim. If G 3/14 does not apply, then the OD or the board can decide under clarity and leave things unchanged.

Whatever the objection would be, i.e. Art 83 or Art 84, it means in any case that the ED granted a patent which should not have been granted in the form it was.

In opposition, the OD could remedy the situation under Art 83 as it is allowed to introduce ex-officio a ground of opposition. The introduction of a new ground of opposition should however remain a very rare exception as the OD should primarily be neutral vis-à-vis the parties. It should however not be forgotten that the purpose of an opposition is not to maintain patents which should not have been granted in the form they were.

Reading this post makes the two comments pop up in my head:

i- lack of sufficiency vs clarity

The claimed parameters seem to be “usual” and known to the One Skilled in the Art. In present case, and as demonstrated by the Daniel, these parameters cannot be properly measured. I thought the relevant objection is A84 (because scope is not properly defined) and not A83 (because measures can be done => A83 OK, but values are obviously questionable => A84 NOK). Am I lost here?

ii- Examination of its own motion

In present case, the A83 objection was considered late, but I agree with Daniel, as the OD rejected opposition, the AR2 was never discussed in first instance, so that the Board should have exercised its discretion to examine on its own motion all the grounds of rejection (A 100 + A84 for features picked from description).

Dear new reader,

Thanks for your comments.

i- Lack of sufficiency vs clarity

The parameters might as such be “usual”, but there are only “usual” if the conditions in which they are measured are properly disclosed in the original disclosure. This is however not the case.

ii- Examination of its own motion

Examination by a board of its own motion is not something boards embark happily. They are strict limits to the possibility of even admitting new grounds of opposition, cf. G 10/91.

It is thus understandable that the board did not want to embark on Art 100 +84, even with G 3/14. I never said that the board should have done so.

As the opposition was rejected, there was no reason for the proprietor to file any AR in opposition. It was thus legitimate and prudent for the proprietor to file new AR when entering appeal. Moreover, in its communication under Art 15(1) RPBA21, the board considered AR1 as being allowable and therefore did not comment on AR 2 and 3.

It was manifestly during the OP that the allowability of AR1 was questioned. This led the proprietor to withdraw the MR and AR1 and to continue with AR2. In the present case, the change of opinion of the board made it thus necessary to admit AR2 as it was filed in time when entering appeal.

The problem lies with the inertia of the ED and of the OD which did not spot the manifest problems with the part of the description from page 3, third line from the bottom, to page 4, line 2. This should have been deleted in examination or queried in opposition.

It is always delicate for an OD to bring ex-officio a new ground of opposition, but the present case warranted such an action.