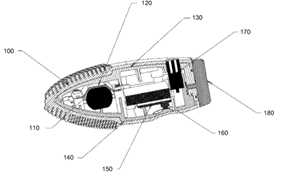

EP 2 941 163 B1 relates to a device that can be described as an oscillating handheld skin cleanser.

Brief outline of the case

The proprietor is Foreo AB of Sweden.

Beurer GmbH filed an opposition.

Prior to the OP before the OD, a first intervention under Artie 105 was filed by the intervener Geske GmbH & Co based on a cease and desist letter received from Foreo.

The OD found that the mere existence of a threat without action for infringement was insufficient for an intervention under Art 105.

Geske filed a suit before the Düsseldorf District Court with the request for the court to hold that Geske did not infringe EP 2941163. This suit was the basis for Geske’s second intervention in the pending opposition proceedings.

This intervention was also held inadmissible by the OD on the grounds that Art 105 required a pending court action either for infringement or for a declaration of non-infringement. While the suit for the declaration of non-infringement had been initiated, it only became “pending” under German law upon receipt of the defendant, and thus they have not yet been “instituted” for the purposes of Art 105(1,b).

During the OP, the OD thus decided on the opposition only on the basis of Beurer’s opposition and upheld the patent in amended form based on AR2. The decision was appealed by Beurer.

Only after the OD had handed down its written decision was Geske’s suit dispatched to Foreo in Sweden Foreo acknowledged receipt of the claim.

In the following, Geske declared a third intervention, to the pending opposition and filed an appeal against the OD’s decision and requested revocation in entirety. Fees for both opposition and appeal were paid.

The board issued summons for OP, whereupon Beurer withdrew its appeal.

The board subsequently issued a communication indicating that although Beurer had withdrawn their appeal, the board was minded to discuss during the OP whether this would necessarily terminate the appeal proceedings, or whether appeal proceedings could continue with Geske as intervener/appellant.

If the latter was the case, the Board saw a conflict with G 3/04 (OJ 2006, 118), making it necessary to refer the case to the EBA.

The proprietor’s point of view

The proprietor requested that the appeal be rejected as inadmissible, the intervention to be deemed inadmissible, and that the appeal proceedings be terminated. A referral to the EBA should not be made.

The intervener’s point of view

The intervener confirmed that they wished to continue proceedings, that they had joined appeal proceedings both as intervener and appellant and requested that the patent be revoked. Further, should the board consider it appropriate to deviate from decision G 3/04, the board should refer the question to the EBA.

The board’s decision

In the board’s reading, Geske’s appeal was directed against two different issues.

The board held that Geske’s appeal inadmissible to the extent that it is directed against the OD’s finding on the admissibility of the second intervention.

The admissibility of the appeal in respect of the substantive issues depends on the admissibility of the third intervention, and on the question whether an intervener entering the proceedings at the appeal stage may or may not acquire appellant status.

Contrary to the patentee’s submissions, the board cannot see that Geske had three bites at the cherry, but, to stay with the patentee’s metaphor, they tried three times to have one bite at the cherry.

Interplay between the rules of the EPC and those of national infringement proceedings

Due to this interplay, an intervener often finds itself between a rock and a hard place when trying to calculate the appropriate three months interval to intervene.

According to case law, Art 105 in this regard requires either a pending infringement action or a pending action for a declaration of non-infringement. The term “pending” , i.e. “instituted proceedings” in the wording of Art 105 is generally interpreted in accordance with domestic law and thus has no uniform meaning. It could mean “when the action has been raised”, or “when the defendant / respondent receives notice”, or even something different.

The board noted that, under German law, a civil law suit is only considered pending once served upon the defendant, sec. 253 Code of Civil Procedure (ZPO), while under German administrative law, raising a suit is sufficient to make it pending, see sec. 91 of the Code of Administrative Court Procedure (‘VwGO’).

Had Geske raised the suit before an administrative court and at the same time requested referral to the competent civil court, the suit would have been considered pending at the time it was raised.

The case gives rise to the suggestion that de lege ferenda, autonomous rules for the application of Art 105 could be incorporated into the EPC.

The board held that the OD’s position on the non-admissibility of the second intervention was correct as such, yet does not categorically exclude that the OD could have decided otherwise.

As argued by the intervener, the OD could possibly have postponed OD or could perhaps have admitted Geske on a provisional basis, as suggested in the literature.

The OD’s decision is however not be overturned by the board as the latter has correctly exercised its discretion.

The board noted that it took the German court a surprising three months to dispatch the claim to Foreo in Sweden. The German court in the absence of a return slip could not establish with certainty when and if the claim had been delivered on the defendant. Only Foreo’s reaction indicated such receipt.

The present case demonstrates that a potential intervener can be faced with legal and factual uncertainties, not to mention the law’s delay.

The board held the third intervention admissible. Thus, the effective date of Geske’s recognised intervention is 15.08.2023.

On that date, the appeal case was pending due to the admissible appeal filed by Beurer.

Admissibility of the referral

The board concurred with the proprietor that there is no apparent non-uniformity and was also in agreement that Art 21 RPBA does not and cannot provide an automatic justification for referral. Rather, an intention to deviate from an earlier decision of the EBA must still meet the requirements of Art 112, which requires either non-uniform case law or the presence of a fundamental question of law. In this latter case, divergence is not required.

The board did however take the view that the legal position of a party to appeal proceedings is normally one of fundamental importance, see also G 03/04, Reasons 1, which concern the definition of the rights and obligations of a party to the proceedings – in this case, the intervener under Art 105 – and poses questions of procedural law of fundamental importance.

If G 03/04 would be revised and the intervener could continue the proceedings in its own right, the appeal proceedings would have to continue with the examination of the substantive issues, namely the opposition grounds raised by the intervener.

If the conclusions of G 03/04 were to be confirmed, the board would no longer have competence to decide and the appeal proceedings would have to end without a decision on the substantive issues, with the consequence that the OD’s decision would become final.

Considerations leading to the referred question

The question to be addressed is thus how the withdrawal of the appeal by Beurer influences the course of appeal proceedings.

For the board, G 3/04 means that an intervener can become an appellant when its intervention is filed during the opposition procedure. If the opponent intervenes in appeal, he can only be considered as opponent provided an appeal is pending.

The board made a distinction between an opposition and an intervention. An opposition does not require an actual or potential conflict between opponent and proprietor. This is different for an intervention as it represents a real and manifest threat to the business interests of the intervener. An alleged infringer faces injunctive relief fights with their back to wall. It is for this reason that the drafters of the EPC found it sufficient to merit an out of time intervention in ongoing opposition.

G 03/04 seems to interpret the term “party to the proceedings” in Art 107, first sentence, as meaning “party to the proceedings leading to the appealable decision”.

The board saw a contradiction between Art 105 and Art 107. In G 3/04 the “status of an opponent” is read as “status of an opponent who had been party to the proceedings leading to the appealed decision, but is not itself an appellant within the meaning of Art 107, first sentence”.

Although, the referring board stated not to be in disagreement with G 03/04, it is however not in agreement that Art 105 in combination with Art 107 must be read in the sense that also a third party intervening only at the appeal stage can never become more than a non-appealing opponent.

The referred question

After withdrawal of all appeals, may the proceedings be continued with a third party who intervened during the appeal proceedings?

In particular, may the third party acquire an appellant status corresponding to the status of a person entitled to appeal within the meaning of Art 107, first sentence, EPC?

Comments

The board developed further legal considerations, based on existing case law of the boards, which are interesting, but do not need to be reported here.

The procedural question raised is certainly worth a referral and can have an influence on many cases.

Without the withdrawal of Beurer’s appeal and the decision of the referring board to consider the intervention admissible whilst Beurer’s appeal was pending, we would not have a referral.

Most probably Beuer settled with Foreo and therefore withdrew its appeal.

The board accepted G 3/04, but found a contradiction between Art 105 and 107.

From the board’s reasoning, an intervener should also not be penalised by procedural delays in national infringement/non-infringement proceedings.

The referred question is of fundamental importance and the referral should be admitted by the EBA.

The board is right that the intervener has a much more difficult position vis-à-vis the proprietor. This aspect played no role in G 3/04.

My own experience in opposition shows that the intervener has always a much more stronger stance against the patent as the original opponent.

The intervener is in the hands of the proprietor. The proprietor can, in principle, start an infringement action at any moment he thinks fit.

It is manifest that a proprietor would rather not have to be confronted with an intervener. However, when tolerating an alleged infringement for too long the proprietor risks its infringement action to become inadmissible, at least in some EPC member states.

Intervention at the UPC

An intervention is also foreseen at the UPC. However, at the UPC the situation is totally different, actually it can be considered as being the opposite of what happens at the EPO.

According to RoP 316 UPC, “Intervention”, the judge-rapporteur or the presiding judge may, of his own motion after hearing the parties, or on a reasoned request from a party, invite any person concerned by the outcome of the dispute to inform the Court, within a period to be specified, whether he wishes to intervene in the proceedings. An intervener shall be bound by the decision in the action.

According to RoP 316A. UPC, “Forced Intervention”, a person can be bound by a decision, even if it refuses to intervene. In such a case the invitation to intervene must include corresponding reasons and must state that the party making the request contends that the person should be bound by the decision in the action even if that person refuses to intervene.

For example, a supplier of goods helping the infringement could be forced to intervene, even if he is not the actual infringer.

T 1286/23

https://www.epo.org/en/boards-of-appeal/decisions/t231286ex1

Comments

Leave a comment