EP 3 711 729 B1 relates to absorbent hygiene products.

Claim 1 as granted lacked N over a Public Prior Use.

The patent was maintained according to AR1.

The proprietor and both opponents appealed.

The board held that claim 1 as granted infringed Art 123(2).

In this blog we will deal with added matter.

The word “good” in relation to the contact between the absorbent core and the acquisition distribution layer (ADL) had been deleted in AR1.

The proprietor’s point of view

The omission of the word “good” in relation to the contact between the absorbent core and the acquisition distribution layer (ADL), was lacking any clear technical implication or meaning. The word “good” could thus be omitted without violating added matter requirements. This was the finding in G1/93.

A “good” contact did not clearly equate to any type or quality of contact. As a closed, layered structure, the ADL being positioned between the top sheet and the absorbent core, which was under pressure when worn, it was technically reasonable for contact to unambiguously occur between the ADL and the absorbent core.

The skilled person would also understand from the original description that it disclosed a range of contact from “close proximity” to “good contact”, all degrees of contact therebetween thus also being disclosed.

It was clear that point contact or intermittent contact would also achieve the liquid distribution function of the ADL such that the qualifier “good” would be seen by the skilled person as being implicit in the contact recited in claim 1.

“Contact” alone, without the qualifier “good”, was also directly and unambiguously derivable from the application as filed as in other parts of the description simply disclosed “contact” between the ADL and the absorbent core.

The opponent’s point of view

In the original description only “good contact” between the ADL and the absorbent core was disclosed. Small areas of contact between the ADL and absorbent core were now covered by claim 1 which the skilled person would not see as being “good” contact. Only two different positions, not a range of possibilities of different contacts between two extremes was originally disclosed.

The board’s decision

The board saw the omission of the qualifier “good” to lack a direct and unambiguous basis in the application as filed.

The board found the word “good” in the expression “good contact” to be technically relevant in the present context. For a skilled person, a good contact, at least in the technical field of absorbent articles, would imply face-to-face contact over a large area between two elements of the article.

Conversely, if two elements are merely “in contact” with one another, at one extreme the expression encompasses merely single point contact over a small area. This latter condition of minimal contact between two elements would not be considered by the skilled person as embodying “good” contact between the elements.

Despite the term “good” being somewhat imprecise, in the context in which it is used in the description it would be understood nonetheless to indicate a certain kind, amount and/or quality of contact.

This type of contact is, however, left completely open through the omission of the term from claim 1. The proprietor’s argument, with reference to G1/93, that the term “good” could be omitted from claim 1 due to it lacking a technical meaning is thus not accepted.

The proprietor’s further contention that “good” contact did not clearly equate to any type or quality of contact was, at least in the present context, not accepted.

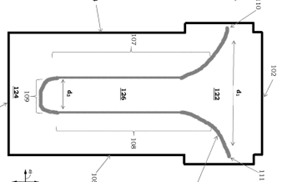

The purpose of an ADL in absorbent articles is to remove liquid deposited on a top sheet and ensure its distribution within itself, but also to ensure swift transfer of the liquid to the absorbent retention part of the core of the article.

In this context, a “good” contact between the ADL and the absorbent core must be contact which efficiently promotes the transfer of liquid from the ADL to the absorbent core such as, for example, by providing a large face-to-face contact area.

Such a contact for promoting transfer of liquid is also suggested in the original disclosure by way of the ADL and the absorbent core being disclosed to be “in close proximity or even in good contact”, the “good contact” thus being evidently superior to mere “close proximity”. Consequently, at least a contact was implied through the expression “good contact”, which the word “contact” alone fails to achieve.

Comments

It is manifest that the term “good” is a relative term which could a priori be considered unclear. How good can good be?

In the present case, the contact between the ADL and the absorbent core has to be “good” in order to promote swift transfer of liquids. Even ambiguous, the term “good” could not be deleted.

In T 241/13, Reasons 1.3.1, it was held that even if an ambiguous feature may be interpreted in a particular way, this is not sufficient to ensure the compliance of an amendment based on that interpretation with Art 100(c).

In the present case, the ambiguous feature could not

Comments

14 replies on “T 0345/24 – Deletion of the relative term “good” infringed Art 123(2)”

I must admit to feeling some sympathy for the proprietor here. The description at para [0198] explains how the ADL is positioned between the topsheet and absorbent core, and more preferably “in close proximity or even in good contact with the body-facing side of the absorbent core”. Setting aside what is meant by “good contact”, I read this as saying that the ADL can be positioned such that it is either not in contact with the absorbent core in the one extreme, to being in “good” contact in the other, with a range of possible contacts inbetween, provided that the ADL is positioned between the topsheet and absorbent core.

I do agree with the board that the term “good contact” has technical significance in this case, but I do not consider that a limitation to “contact” instead of “good contact” infringes A123(2).

@ HKJ

I also stumbled over the sentence in § [0198] or [0196], but when you accept that the term the term “good contact” has technical significance in this case, then you have to accept that G 1/93 applies and therefore it cannot be deleted.

To me “in close proximity” does not make much sense in view of the function of the ADL which is to achieve a good distribution of fluids from a discharge area to the entire absorbent core whilst attaining excellent perceived dryness performance.

This aim is only achieved with a good contact. In this respect, even the terms “more preferably” in § [0198] or [0196] are somehow misplaced as the contribution to the art resides in the composition of the ADL. Without a good contact the ADL does not serve its purpose.

Without speculating on the reasons the board could have had to be so strict, I have noted the insistence of the proprietor to leave out the term “good” in any AR he has filed in opposition and in appeal. The proprietor only played with the composition of the ADL.

It might well be that, in its decision, the OD held “good” as being sufficient in view of its relative charactr and not having a technical function. It can however not be expected that the board will necessarily endorse the OD’s position.

At least when entering appeal, it would have been better for the proprietor, in view of the valid RPBA to file at least one AR in which the contact was to be “good”.

The proprietor might have had its reasons to do so, but its whole strategy failed, also in view that it filed an AR during OP and thereby reordered its requests. See the parallel entry in my blog.

Thank you Daniel, I appreciate your reply. I agree with you that the term “in close proximity” at para [0198] does not make much sense in view of the functioning of the ADL when in use. Maybe my unease about this case is better expressed in this way: the meaning of feature 1.3 in claim 1 requires to be interpreted in the light of the description (A.69) and therefore must be understood to be a contact as described at para [0198], which was described in the application as filed, therefore no infringement of A.123(2). Or another way of looking at it: if the skilled person would read para [0198] as meaning that contact equals “good contact”, as I think we both do (at least when in use), then that limitation should be read into the interpretation of claim 1, so again no infringement of A.123(2).

@ HKJ,

I fully understand your point of view, but I am still unable to share it.

What you suggest is to read in the claim a limitation found in the description. The answer to this question will most probably be given in G 1/24.

I do however doubt that, even after G 1/24, it will be allowable to read into a claim a limitation which can only be derived from the description. There is also, prior to the referral, a long line of case law against this possibility. Other boards considered that for deciding upon Art 123(2) the description ought to be taken into account. To me, the key notion defined by numerous decisions of the EBA relies on the concept of “what is directly and unambiguously derivable”. This concept should not be jeopardised with G 1/24.

The idea that a patent is its own dictionary also goes along this line of thoughts, and is also not acceptable for me. If a third party is systematically obliged to consult the description for finding the true meaning of claimed features, why then bother having claims?

Defining a product during its use does also not seem a solution as it generally introduces a lack of clarity. A product claim should define the product with its technical features rather than by its use.

On the other hand, a mention of the use, for instance “product for” might imply a limitation. A patch “for treating wrinkles” is not a patch “for alleviating pain”, even if they have an identical structure, see EQE Paper C 2012.

I confess to having given the docs only a brief and cursory review but wanted to join the discussion before it peters out. The case reminds me of one in which I was involved, about 25 years ago, when multiple serious competitors all opposed the patent. With good reason, I thought. The contribution to the art was simple to implement, but delivered a momentous technical effect. I was looking forward to the oral proceedings but they turned out to be painful. One voice in defence of the claims, followed by ten advocates (more or less the entire industry) who, one after another, explained why maintaining the patent would be unconscionable. The TBA duly revoked the patent.

Here, we see a divisional, also opposed by leading players, and an OD provisional opinion finding all requests to offend Art 123(2) EPC. If you can’t get a good patch in, by filing a divisional, all hope is gone, no?

I don’t know whether useful claims could have been obtained and enforced but I) the in house attorney handed over to outside counsel only after the EPO granted the patent and ii) the patent family is large, with multiple members in the USA.

As a patent attorney in private practice, I note here i) how cases that are not “high tech” can nevertheless be very valuable commercially and ii) the fate of an entire patent family/holding/portfolio can depend on just one ill-advised word in claim 1.

Dear Max Drei,

The field of absorbent hygiene products has always been a very disputed field. The rate of oppositions has however gone down in recent years. They are indeed low tech products, but the sheer number of absorbent articles sold every day makes patent a worthwhile tool to hinder competitors.

The patent at stake does not stem from a divisional application, but this does not change the fact that there was, in the board’s opinion, a clear problem of added matter. Even if the proprietor had his reasons to refuse adding “good” to “contact”, its strategy is difficult to understand. A functional definition of the ADL and its position could have been envisaged. Is it really worth losing a patent for one word?

In the original description one reads: “The use of an ADL in combination with the fluid distribution structures and/or interconnected channels of the present invention lead to an extremely good distribution of fluids from a discharge area to the entire absorbent core whilst attaining excellent perceived dryness performance”. A good representative could probably formulate something which could have avoided a long discussion whether good had to be associated with contact. .

My apologies Daniel, for my not being clear. The divisional that I mentioned is the backup patent application in case the parent (ie the patent here under discussion) attracts an opposition. One would think that in the prosecution of the divisional the pitfalls of the parent would be avoided. Not here though, it seems.

Dear Max Drei,

It is difficult to say whether a parent patent attracts more oppositions than a divisional.

The EPO certainly could publish figures in this respect. I do however doubt that it will do so.

The subject-matter of the claims in a divisional can either attempt to provide a greater scope of protection or a more reduced scope of protection in combining more details stemming from the original disclosure.

What I have noticed when looking at lots of published decisions is that actually patents granted on the basis of divisional applications are rather prone to problems of added matter under Art 76(1), even if the description is the same and the original claims are kept in the description in the form of claim-like clauses.

With respect to divisional application and their filing, it is worth noting that TEVA has been fined by the EU for abusing the system of divisional applications. It kept divisional applications simmering so that the competitors were never sure what the scope of protection eventually looked like. It is not the fees introduced for multiple generations of divisional applications by the EPO which will avoid them. They are peanuts compared to the benefits that can be gained, even if the annual fees have to be back paid at filing.

Thanks again, Daniel, but again I must apologize for not making myself clear. Applicants from the USA often file a divisional as their patent application gets close to grant. Then, when the granted case gets opposed, they have a pending divisional which they can prosecute with the benefit of knowledge of all the validity attacks filed by the opponent. This strategy they call “Keep something pending at the Patent Office”. TEVA, as one example, found the strategy useful.

You observe that divisionals often attract Art 123(2) objections. That makes sense, especially when applicants try to with the divisional to claim subject matter that stretches the envelope (of scope of protection) more widely than they thought possible in the original patent application that they have carried through to grant.

Of course, it is not only the applicant that learns from the opponent’s written submissions. So too does the ED examining the divisional. Given the hours of effort put into preparing an opposition, it would be surprising if the written Grounds of Opposition did not inspire an ED looking at the div to formulate a range of objections which had not occurred to the EPO Examiner in charge of examining the parent.

Divisional filings are OK if each of them is to protect a distinctly different invention. That’s not an abuse, is it? But TEVA (I suppose) kept filing successive generations of divisional but always for the same invention. Was that their abusive act?

Dear Max Drei,

It is well known that divisional applications are also filed shortly before OP. If the result of the OP is positive for the applicant, the divisional is simply dropped by not paying the required fees. Third parties will thus never know of such moves.

If the result of the OP is not satisfactory, then a divisional will be pursued. I observed that often the divisional has even a broader scope that than what has been reached at the OP with the parent.

The temptation is however great to squeeze out the maximum out of a divisional. Just look at the numerous divisional applications filed by Edwards Life Science for its low profile delivery system for transcatheter heart valve. The grand parent application dates back to 01.05.2009 and we are now at the 4th generation, the latest 2 having been filed in 2020.

There is nothing against filing divisional applications, but when you see divisional applications still running 15+ years after the parent’s filing, the idea of abuse comes automatically to mind.

From what I understood, TEVA was fined as it kept divisional applications and withdrew them shortly before a negative decision was expected. By doing so TEVA kept competitors in the dark of the real scope of protection it was after. This is clearly an abusive use of divisional applications. The few 100€ to paid for each further generation of divisional applications is peanuts and not a deterrent not to abuse the system.

Thanks, Daniel. On the issue of abuse of the privilege to file successive generations of divisional application, some years ago, the EPO created a cap, an inextensible time limit on the filing of divisionals.

But that Rule didn’t last long, did it? I wonder why the EPO cancelled the Rule. Was it perhaps a combination of i) outcry, internationally by the EPO’s bulk corporate users (who tend to get what they demand), together ii) recognition by EPO management that the more divisionals filed, the more fees the EPO gathers into its coffers, and iii) no other Patent Office following the EPO’s lead.

I can’t think of any reasons other than those three. Can you?

Dear Max Drei,

I was in active service of the EPO when the decision was taken to impose a time limit for filing divisional applications, and then to rescind it and more or less coming back to the original situation. I therefore cannot say much about the reasons for adopting it and later for rescinding it. I hope for your undestanding.

I can just say that the fear of being inundated by divisional applications played a role, and hence that filing of divisional applications could be abused, lead to the adoption of the time cap for filing divisional. Where this fear came from will remain private, as far as I am concerned.

The time cap was then rescinded as it appeared that deciding when examination started was not always easy to determine. I even remember some board’s decision on this topic.

I can just say that the system was felt too complicated and therefore abandoned. Instead came the fee for the further generations of divisional applications. Only, the first divisional was for free. As we can see this is not a deterrent for applicants.

I will leave it at this.

Just one more thought, Daniel. You are an in house patent attorney contemplating filing an opposition at the EPO. You see on the Register that a divisional is on file but not yet examined. Will you file that opposition? Or might you hold back, and NOT file it, out of fear that the proprietor/applicant will be able, with the divisional, to avoid the mistakes that render the granted parent vulnerable to revocation and so bring to grant a patent with claims that you infringe, in a patent that you will struggle to revoke?

In other words, one more reason to file divisionals (in addition to the standard “keep something pending at the PTO” US-style thinking, is to deter your competitors from filing oppositions at the EPO.

Nothing wrong with that though, is there (if only because it’s mainly a first generation divisional thing)

Dear Max Drei,

Oppositions are normally filed when a freshly granted patent can be a hindrance for products either already marketed or on the verge of being marketed. What appears more important to me is that by filing an opposition, you draw the attention of the proprietor to your own products or methods. This seems to me a much stronger reason not to file an opposition that the existence of a non-examined divisional application.

I have never seen oppositions filed for fun or for training purposes, as an opponent once said in the early EPO days. In those early days, oppositions were mainly filed by German opponents as they knew the benefit they could gain from oppositions.

You also ought to keep in mind that there is a time limit of 9 months to file an opposition after the mention of the grant. I do therefore not think that the presence of an unexamined divisional is necessarily a deterrent for filing an opposition.

As the divisional cannot extend beyond the parent, filing a divisional is also not as easy as filing a “normal” application. This explains the famous claim-like closes=original claims inserted at the end of the description of the divisional, another US specificity. I have also rarely seen applications filed without claims, but for divisional applications.

When realising that not even 20% of granted patents survive an opposition at the EPO, it might be worth filing an opposition, even if there exists a non-examined divisional. Divisional applications of second and more generations are on general filed after expiry of the opposition period of the parent/grand parent application. Such further generation divisional are in general very open to objections under Art 76(1).

With the costs of filing a lack an invalidity action at the UPC, filing an opposition remains a cheaper alternative within 9 months from grant.