EP 3 166 825 B1 relates to an adaptive trailer oscillation detection and stability control.

Brief outline of the case

The opposition was rejected and the opponent appealed.

The board held that claim 1 as granted lacked N over D4, a document classified “Y” in the ISR established by the EPO.

The proprietor filed AR A in which claims 1-14 as granted were deleted.

The board decided maintenance according AR A, and remitted to the OD for the adaptation of the description.

The case is interesting as it has applied G 1/24 when construing the claim and decided that since the description allowed a broader meaning than the possible strict literal reading of the claim, claim 1 as granted lacked N.

The OD’s decision

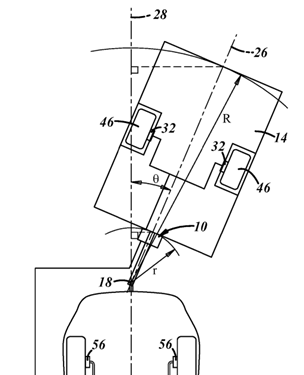

The OD took the view that the yaw rate sensor disclosed in D4 did not measure the rate of trailer deflection around the hitch pivot point (18), and that the device of D4 did not discriminate between oscillatory and a non-oscillatory events.

The OD also noted that the yaw angle and the angle about the hitch pivot point, i.e. the trailer or hitch angle, “are referred to different axis of the trailer“.

Consequently, their corresponding angular rates may differ. For example, in a curve of constant radius, the hitch angle remains constant, with a rate of zero, while the yaw rate of both the tractor and the trailer is the same and non-zero.

The proprietor’s point of view

The proprietor agreed with the OD’s view, and also argued that the absolute yaw rate and the rate of angular trailer deflection about the hitch pivot point (18) were distinct physical quantities, even if their values coincided during straight-line vehicle operation.

These two physical quantities did not become the same physical quantity simply because their values coincided in one specific condition. The claim clearly defined the angular rate sensor as being configured to measure the rate of angular trailer deflection about a hitch pivot point (18).

The opponent was undoubtedly broadening the subject-matter of claim 1 too much. In particular, the wording of claim 1 excluded a single yaw rate sensor as the angular rate sensor. Figure 3 depicted a “gyro” for the angular rate sensor but such a sensor was not mentioned in the description. Furthermore, gyroscopic sensors were not excluded by the wording of claim 1, but at least two gyroscopic sensors embodying the features F and F1 of the angular rate sensor would be needed.

The board’s decision

In the present case, the doard judged that the opponent’s interpretation of features F and F.1 of claim 1 is justified.

The board agreed with the proprietor that, when the claim is read in isolation, features F.1 and F.2 can be read literally such that the angular rate measured by the sensor is the rate of the angle made by an axis passing through the hitch pivot point with respect to a reference axis.

However, in accordance with G 1/24, the description and drawings shall always be consulted to interpret the claims.

This implies that claim interpretation requires taking into consideration the wording of the claim and the content of the description.

As was correctly pointed out by the opponent at the OP, the patent discloses a gyroscope sensor, i.e. a sensor for measuring the yaw rate, as the only specific implementation of the claimed angular rate sensor.

This is not only denoted in figures 3 and 4 as a “gyro”, but the description of the preferred embodiments of the invention also describes the sensor as a raw angular rate sensor, i.e. a sensor measuring absolute yaw rate.

A measure of the yaw rate of the trailer coincides with the rate of the angle made by an axis passing through the hitch pivot point (18) with respect to a reference axis, when the yaw rate of the towing vehicle is null or negligible, e.g. when the towing vehicle is moving along a straight line.

Consequently, contrary to the proprietor’s submissions, when consulting the description the claim cannot be strictly construed as requiring the measurement of the rate of the angle made by an axis passing through the hitch pivot point (18) with respect to a reference axis under any conditions or movements of the towing vehicle.

The claim must be construed in a broader manner, i.e. as only requiring that the rate of the angle made by an axis passing through the hitch pivot point (18) with respect to a reference axis can be made under certain conditions.

One such condition is the most common condition in which the yaw rate of the towing vehicle is null or negligible. Accordingly, since D4 discloses a yaw rate sensor on the trailer, which measures the rate of the angular deflection about a hitch pivot point when the towing vehicle is driving in a straight line, it follows that features F to F.2 are known from D4.

With regard to feature G, D4 detects trailer oscillation using signals from both the yaw rate and lateral acceleration sensors. The proprietor also confirmed this. Once the device of D4 determines an oscillation event, it distinguishes between trailer oscillation and non-oscillation events. Otherwise, the device would not be able to detect oscillation events.

The proprietor’s argument on non-disclosure of features K and L does no longer hold either, since features F.1 and F.2 are disclosed in D4.

Comments

Up to now most decisions of boards related to the fact that the description limited the meaning of a claimed feature, clear on its own for the skilled person. See e.g. T 1846/23, commented in the present blog, or T 2027/23, also commented in the present blog.

We now have a decision in which a broader meaning can be given to a feature which, upon reading of the claim would be limiting.

In other words, G 1/24 goes in both directions.

In a first situation, a limiting feature in the description will not be taken into account when interpreting a broad claim, whereby the patentability of a claim will be assessed on its broad meaning.

In a second situation, a limited meaning of a claimed feature can be ignored when the description allows a broader meaning, whereby the patentability of the claim will be assessed on the broader meaning found in the description.

This is exactly what I have suggested in my blog entry of 15.09.2025.

In the latter, I insisted upon avoiding discrepancy between claims and description, but this the same as in the two above situations.

Comments

4 replies on “T 1849/23-Application of G 1/24 when the description allows a broader interpretation”

Is it accurate to summarize the application of G 1/24 as: “Any discrepancy between the claim and the description will be interpreted to the patentee’s disadvantage”?

@ Extraneous Attorney,

I would certainly not go as far as you want to summarise G 1/24.

I would rather summarise G 1/24 as follows: “Any discrepancy between the claim and the description can be overcome by the patentee by amending the claim”.

If the patentee does not want to amend his claim in procedures before the EPO, then it is to him to bear the consequences.

Case law, past G 1/24, is very clear in this. T 2027/23 was even over explicit in this respect: no interpretating somersaults.

I am well aware that when G 1/24 was issued, and insisted upon the fact that the description has always to be consulted, a lot of hope was, that boards would always take into account what is in the description to interpret the claim, and not to merely stick to the claim. This is manifestly not the direction they are taking.

The EBA has not said that what matters is what is found in the description and has to supersede what is stated in the claim. This would in any case be contrary to the primacy of the claims. If claim language can be disregarded in view of what the description saya, then why bother about claims?

If the same interpretation of a claim between the EPO and courts deciding in post grant procedures has to be ensured, then the description and the claim ought to be aligned when a patent leaves the EPO. This is what the board have stated unmistakenly in their post G 1/24 decisions.

I would say that what is called a spade in the description has to be called a spade in the claim, even if the claim speaks about a gardening instrument.

If the description mentions a gardening instrument, but the claim mentions a spade, then the gardening instrument has to come into the claim.

For me the logic behind the board’s position is pungent.

With G 1/24, the days of the patent being its own dictionary might have gone for good.

This might not be to the liking of many patentees, but will certainly improve the position of third parties.

Last but not least, one day a party is patentee, another day third party. The patentee cannot always win.

@ Daniel X. Thomas,

Thank you for your thorough response. Your last point is very relevant. Patent attorneys, myself included, do tend to forget that they can be on the side of a third party (alleged infringer, opponent, intervenor, whatever) instead of being on the patentee’s side.

@ Extraneous Attorney,

My last comment is the result of my experience. When working in a specific technical area with lots of oppositions, parties are often the same; once they appear as proprietor, once as opponent. We then all have to meet regularly.

I have chaired and taken part in many OP, but seen regularly some representatives misbehaving towards their colleagues and/or to be rude to the division. I always wondered why such an attitude was at all necessary.

If the case is hopeless, the best representative will not achieve miracles, but this is not a reason to let out one’s frustration to the other party or to the deciding body.

In general, bad representatives misbehave, good ones do their job correctly and do not expect the deciding body to be impressed by one’s forthright attitude.