EP 2 986 030 B1 relates to a hearing aid provided with an antenna to enable wireless communication with other devices, e.g. with another hearing aid in a binaural hearing-aid system.

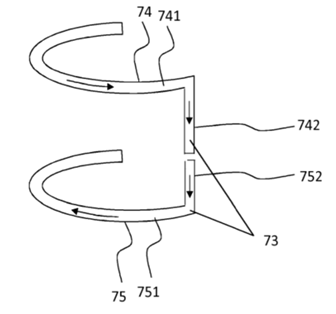

Claim 1 as granted proposes a hearing aid comprising an antenna with a specific geometry. The antenna is supposed to comprise a “first branch” (74) and a “second branch” (75), each having a length of approximately a quarter of a wavelength. The first branch includes a “first segment” (741) that “extends in a first plane” and the second branch includes a “second segment” (751) that “extends in a second plane”. The claimed solution is characterised in that the “first feed point” (742) and the “second feed point” (752) of the antenna are “located between the first plane and the second plane”.

Brief outline of the case

The patent was revoked since claim 1 as granted was lacking N over D1=US 2014/0010394, not mentioned in the ESR. AR3-4 infringed Art 123(2) and AR5-6 were not admitted.

The board confirmed the revocation.

The case is interesting in view of the claim construction by the board in application of G 1/24.

The proprietor’s point of view

In its written submissions, the proprietor argued that G 1/24 argued that the description and drawings must be referred to when interpreting a claim, which would thus lead the skilled person naturally to what the proprietor’s calls a “practical implementation” scenario.

The proprietor defined the skilled reader as an engineer in hearing-aid antennas who, upon reading the claim as a whole, would understand the components to be very thin, like a flexprint of 1mm thickness.

From this, the proprietor argued that the skilled reader could interpret the “planes” as mathematical abstractions, but would then understand that there was no technical meaning to be associated with the requirement in claim 1 that the physical “feed points” must lie “between” those “planes”.

Likewise, the proprietor emphasised that a “feed point” in the context of claim 1 must have a physical extension. It further contended that, the skilled reader would understand that the “feed points” are not located on the “segments” and that the “planes” must be the physical planes of the segments themselves, implying a spatial separation between those feed points and the segments.

Following G 1/24, the skilled reader would, in the proprietor’s view, consult the description and note that there was nothing that spoke against what the skilled reader had understood from the claim alone.

The proprietor further argued that this reading was supported by the conclusions of T 190/99 and of the UPC decision UPC_CFI_373/2023.

During the OP before the board, the proprietor also argued that the board must choose one of both interpretations, see below, since in its view, the two interpretations cannot not co-exist. The “abstract, mathematical” interpretation would not make technical sense.

The board’s decision

Concerning the construction of claim 1, there is, in the board’s view no objective reason to restrict the interpretation of the term “plane” used in claim 1 to a purely physical one: the opposed patent itself uses this term in an “abstract, mathematical” context.

As a result, several constructions of claim 1 would objectively occur to a skilled reader, including:

– the construction adopted by the OD, involving mathematical “planes”, and

– the proprietor’s preferred so-called “practical implementation” scenario where “planes” are defined by antenna segments.

G 1/24 indeed requires that the description and drawings be “consulted” or “referred to“, but not that the scope of the claimed subject-matter be limited to the embodiments described therein.

As confirmed in, for instance, T 1465/23,Reasons 2.4, the description may, for example, be consulted to define the skilled reader, but this does not preclude interpreting claim terms according to their common meaning in that field, nor does it invalidate broader, technically viable interpretations.

Therefore, the “abstract, mathematical” construction remains an equally valid interpretation of the claim’s language, even after “consulting” the description and the drawings.

Terms used at multiple places in the description all belong to the realm of mathematics and the language of mathematics is part of the skilled reader’s CGK to describe geometric relationships between components. In addition, the whole description is silent as to a “plane” made of any physical material.

Moreover, the board found the proprietor’s reliance on T 190/99 to be misplaced. That decision, see Reasons 2.4, concerns ruling out interpretations that are “illogical or which do not make technical sense”, cf. T 10/22, Reasons 2.3. The “abstract, mathematical” interpretation is neither; it is rather a standard method of geometric definitions in engineering.

The proprietor’s reference to the UPC decision of the LD Dusseldorf UPC_CFI_373/2023 is, if anything, counter-productive to its case, as Headnote 1 of that decision explicitly states: “The claim must not be limited to the scope of preferred embodiments”, which is precisely what the appellant’s “practical implementation” scenario seeks to do.

The proprietor’s premise that a deciding body must choose a single “correct” interpretation is flawed from the outset. Instead, the deciding body’s duty is to assess a claim against all interpretations that are technically sensible to the skilled reader.

The board is aware that other decisions, such as T 367/20, Reasons 1.3.9, have suggested that a deciding body must choose a single “correct” interpretation where mutually exclusive interpretations exist.

Yet, in line with its established jurisprudence, cf. T 405/24, Reasons 1.2.3, the present board finds that the decisive criterion in this regard is what the reader skilled in the respective technical field would understand from the technical terms of a claim.

As explained in Reasons 1.2.3 of T 405/24, an approach that forces a choice for a single “correct” interpretation, such as the one derivable from the description, would jeopardise legal certainty.

Such an approach could lead to the untenable result that some provisions of the EPC, such as Art 123(2), might be rendered ineffective. The board thus held that all technically reasonable interpretations are to be taken into account instead.

Comments

Besides T 367/20, which was taken pre G 1/24, all decisions cited here, T 1465/23, T 405/24 as well as the present one, were all taken by board 3.5.05 in various compositions.

They have one point in common: the skilled person is not limited to the interpretation it can derive from the description, but the skilled person can have other interpretations, and the interpretation which can be derived from the description is not necessarily binding.

It will be interesting to see whether other boards follow the same route.

Comments

Leave a comment