EP 3 497 276 B1 relates to a laundry washing machine.

Brief outline of the case

The opposition was rejected and the opponent appealed.

According to G 1/24 the board interpreted claimed features in the light of the description.

After interpreting claimed features in the light of the description, the board decided that claim 1 as granted was lacking N over D2 not mentioned in the ISR established by the EPO.

As the further AR were either lacking N or were unclear, the patent was revoked.

The features at stake

- an adjustable damping characteristic

- a constant damping characteristic

- arranged at a distance from one another in relation to the transverse axis (5) and adjacent damping units (6)

The proprietor’s point of view

Adjustable damping characteristic

The proprietor itself argued that it was irrelevant which damping property could be modified. Rather, what mattered was that the damping units differed in their design, with one allowing a damping property to be modified and the other not.

The proprietor also argued, that the description gives a consistent and uniform interpretation of “adjustable”, to be understood as “variably controllable during operation”, actually by means of electronic control.

The proprietor further argued that if the term “adjustable” was interpreted too broadly, the problem to be solved in the patent, namely to reduce operating noise by making the damping characteristic adjustable in all operating conditions, would not be achieved. Not being able to adjust the damping characteristics forces to make compromises.

Constant damping characteristic

With regard to a “constant” damping characteristic, it is sufficient if the damping characteristic remains constant over time or location. However, it can still be changed.

Arranged at a distance from one another in relation to the transverse axis and adjacent damping units

The proprietor argued that the phrase “relative to the transverse axis’” should be understood to mean that one damping unit is located closer to the front wall and the other damping unit closer to the rear wall of the housing. This follows from the position of the transverse axis. Furthermore, the term “adjacent” defines that the damping units were located next to each other and not offset around the circumference.

Damping units are arranged one behind the other in the direction of the transverse axis and cannot lie in a normal plane to the transverse axis. “Adjacent” is to be interpreted as “adjacent in the direction of the transverse axis”.

For the proprietor, mutually offset damping units would no longer be “adjacent” within the meaning of the contested patent.

The board’s decision

Adjustable damping characteristic

For the board , an “adjustable damping characteristic” simply means that it must be possible to adjust it, i.e. vary, a damping characteristic in some way. The interpretation therefore includes both the possibility that the characteristic can be continuously changed during operation and the possibility that the property can only be adjusted before installation, perhaps even only in steps, and cannot be varied during operation.

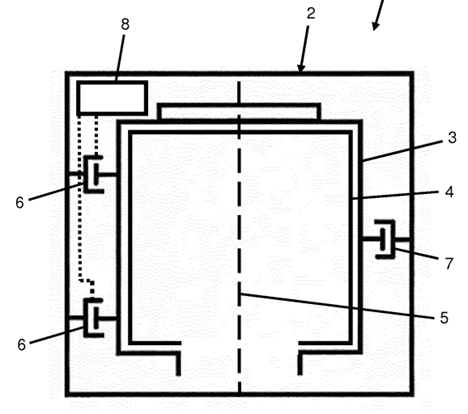

Looking at the description, it can be concluded that the embodiments show damping units with damping force that can be variably adjusted during operation by means of an electronic control system (8).

The board held that this does not justify interpreting “adjustable damping characteristic” in claim 1 more narrowly than its literal meaning and restricting it to adjustability during operation, especially not by means of electronic control.

The board concurred with the opinion, that not being able to adjust the damping characteristic, needs to enter certain compromises. This was however not a reason to accept a limited interpretation of the claimed feature.

Constant damping characteristic

The board interpreted the term “constant damping characteristic” to mean that any damping characteristic cannot be adjusted at all.

There is no direct definition of “constant” in the contested patent. Contrary to the proprietor’s broad interpretation based on the litteral meaning of the word “constant”, the board arrived at a different interpretation.

According to the description, the term “constant damping characteristic” is used as an antonym to the term “adjustable damping characteristic”. Based on this indirect but clear definition given in the description, the term “constant” is therefore to be interpreted as “non-adjustable”, i.e. unchangeable.

Arranged at a distance from one another in relation to the transverse axis and adjacent damping units

The board observed that, “with regard to the transverse axis” is not to be equated with “in the direction of the transverse axis” or “in a direction parallel to the transverse axis”.

At most, this requires some kind of relationship between the spaced arrangement and the transverse axis. However, this relationship does not have to relate to the direction of the axis. It could, for example, also be expressed by the fact that the two damping units are the same distance from the transverse axis.

The term “adjacent” merely defines the claimed subject matter in such a way that no further damping unit is arranged between the two adjustable damping units. Accordingly, the damping units can be arranged offset both in the circumferential direction and in the direction of the transverse axis.

Both arrangements are “adjacent”, and in both arrangements there is a reference to the transverse axis with regard to the property “adjacent”. There is therefore no basis in the contested patent for a restrictive interpretation of the term “adjacent” as “adjacent in a specific direction”.

Although the description and figures must be consulted when interpreting the features of the claims, cf. G 1/24, headnote, the description of a specific embodiment may be disregarded in accordance with the principles developed in case law with particular reference to T 2684/17, T 1871/09, T 1473/19, T 1465/23, T 161/24, and T 1999/23, with reference to the CBA, 10th edition, II.A.6.3.4, and cannot, as a rule, be used to restrict the interpretation of an object claimed in more general terms.

That one damping unit is located closer to the front wall and the other closer to the rear wall would not be technically feasible and therefore not a technically meaningful definition for all laundry drums falling under the claimed subject matter.

The definition given if the description is only valid if the axis of rotation of the laundry drum runs from the front wall to the rear wall, but not if the laundry drum has a vertical axis of rotation

The board therefore saw no reason in the description of the embodiment to interpret the term “adjacent” restrictively as “adjacent in a specific direction”.

Comments

When interpreting claimed features after having consulted the description, the present board confirmed a long line of case law, that a clear claimed feature cannot receive a limited interpretation on the basis of the description.

One conclusion can be drawn from the present decision: giving a limited interpretation of claimed features in view of the description, was never and is not any longer possible at the EPO.

This part of the theory that a patent is its own dictionary can be relegated to oblivion.

We just have to wait of a series of decisions dealing with the broadening of claimed features in the description, for the complete theory of the patent being its own dictionary to be fully relegated to oblivion.

What is valid for a limiting interpretation should be equally valid for broadening of features. In this case, the possible broadening has much more deleterious effects for third parties. I refer here to the Agfa/Gucci case, commented in the present blog.

This might not be the consequence of G 1/24 lots of representatives wished to see emerging.

On the procedure

It is interesting to note that D2 bears the same classification unit as the patent, and yet, it has not been found when the EPO established the ISR.

Either the examiner did not read the description, and if he did, he read the limitations queried by the board into the claims.

Comments

4 replies on “T 1846/23 – Application of G 1/24 – No limiting interpretation of claimed features”

I wonder how reasonable it is, Daniel, to expect an EPO Examiner to examine an ordinary patent application so closely and thoroughly that a competitor is left unable to find any plausible grounds of opposition. Conversely, not examining at all strikes me as unacceptable. So how does EPO management decide how much time an Examiner shall be given, to examine each patent application on their docket.

As to inconsistencies, I’m thinking that the EPO might be going through the motions of adopting a “Buyer Beware” or “Be careful what you ask for” attitude. You know, like with Art 123(2). If the patent dies under Art 100(c) the EPO is quick to shrug its shoulders, with the thought that Applicant should have been more careful. Why not the same policy, going forward from here, with inconsistencies?

Dear Max Drei,

What do you understand under an “ordinary patent application”? When searching and examining, every application is “ordinary”. It is only later that the odd application turns out to be a nugget. Patents ending on the market are the top of the iceberg. Most of the patents represent the underwater part of the iceberg and never end up on the market. They are not useless, but represent a big reservoir of technical knowledge. This is the second aspect of patents.

For those patents not ending on the market, it might not be worth investing too much time. However, the problem is that as examiner you do not have a clue of what could happen to it. In my early days, I got an application of a chap called Ray M. Dolby. It is only later that I realised that it was a nugget for audio magnetic recording.

I can agree with you, that it is impossible to expect an EPO Examiner to examine an ordinary patent application so closely and thoroughly that a competitor is left unable to find any plausible grounds of opposition.

Indeed, a compromise between time spent and quality of the result as to be achieved. It is well known for instance that the probability of finding relevant prior art diminishes drastically the more time is spent. The question here is when is it reasonable to stop searching. The idea that a search revealing a X document is a good search is still polluting brains at the EPO.

A part cases which are infringing Art 123(2) or 76(1), the main discussion in examination is always about novelty and/or inventive step. Sufficiency is rarely raised in examination as the EPO examiner does not have the possibility to carry out experiments.

Clarity is important and not merely a formal point. How can you decide that the subject-matter of the claim is new and inventive, if you do not know what the claim means.

A further aspect is to take into account possible broadening or limiting interpretations of claimed features in the description. If the applicant wants to limit or broaden the claim with the help of the description, he should be invited to bring the limitation or the broadening in the independent claim. Why should third parties have to dig deeply in the description to discover what claimed features are covering? And we arrive at the alignment of claims and description.

However, when looking at the prior art submitted the opponents, it is in less than 10% of the cases that they come with prior art which truly could not be found in the EPO’s search files. I am thinking here of PPU, PhD dissertations and the like.

In the vast majority of the cases, opponents come with prior art which was available in the EPO’s search files, but, for whatever reason, not found during the original search. Sometimes the opponent even comes with prior art under Art 54(3).

For all those patents which were granted without having found out the truly relevant prior art, you might consider irrelevant that claims and description are not aligned. The problem is like above: when examining, the examiner is manifestly not aware of the potential inconclusiveness of his search. There is no way out, and at least the ED should care about avoiding inconsistencies between claims and description.

Shrugging one’s shoulder is not an appropriate reply to the problem. This work has to be done, and this is the more so, since Art 84 is not a ground of opposition.

Daniel we agree on so many things, don’t we. The issue of “conforming the description”, however, continues to be a difficult one.

It occurs to me now, thanks to your reply, that it might be premature to undertake the often huge task of conforming the description before we know accurately what is a) the state of the common general knowledge and b) all the X and Y documents crucial to patentability. Even if we delay until a 71(3) can be issued for the claims, we likely still don’t know all the prior art that a petitioner for revocation is going to be applying to the B publication, in post-grant proceedings.

There is an old saying about it being better to do any particular job just once, and correctly rather than more than once and imperfectly. In general, that makes a lot of sense, don’t you think?

If the courts and the public are grieviously handicapped by a description that is not accurately conformed (and personally I doubt that they are) why not then do the conforming just once, and accurately, only after post-grant inter Partes proceedings have been initiated? At least then the court has only one description to consider, and not two, the second of which might be “conformed” to the “wrong” prior art.

There is a thing called “proportionality”. Precious resources (Examiner hours at the EPO, for example) should be conserved whenever possible, and only expended when necessary.

Dear Max Drei,

I understand very well that the “issue of “conforming the description”, however, continues to be a difficult one”, for you.

You have an interesting idea, but it forgets one fundamental aspect I have tried to make clear in my preceding replies. An ED will never know whether he is dealing with a nugget, or whether an opposition will be filed. If an opposition is filed, one conclusion to be drawn is that the patent presents some kind of threat to the opponent, so he wants to get red of it or to limit its scope.

Another aspect which should not be forgotten, is that the number of patents opposed is rather law, as it costs money for the opponent, and also for the proprietor. It is also interesting to see that technical areas in which oppositions are filed vary with time.

Absorbable devices have always played a role, hair colouring or polymers as well, but when you look at pacemakers, a domain with lots of oppositions 20 years ago, nowadays, there are hardly any oppositions in this area. In general, oppositions occur most in up coming technical areas, as it becomes important to keep competitors out of the market. One prime example are wind turbines and gene based pharmaceutical products.

It follows that I cannot subscribe to your idea to wait until an opposition has appeared to actually align claims with description. I repeat that, if the ED had done its job we would not have ended with G 1/24 and the Agfa/Gucci decision of the UPC.

This is why I maintain that aligning description and claims is an absolute necessity before grant and after maintenance in amended form.

Whether a post grant court is “grievously handicapped by a description that is not accurately conformed” is irrelevant, as it is the EPC which requires this.

In this respect case law of the boards has confirmed the fact that the description cannot be used to give a claimed feature a more limited or broader interpretation through the description. This defeats the whole purpose of the claims, if third parties have to delve deep in the description to understand what the scope of the claims could be.

We might agree on a lot of thing but in this case, I have to disagree with you and with lots of your colleagues. Once a feature is introduced in an independent claim in order to limit it, it cannot be left as merely optional in the description. If some embodiments are superseded by prior art, it is not correct to continue alleging in the description that those are still covered by the amended claims. I do not say that they should be deleted, but it should be made clear that they do not any longer represent the claimed invention. It is as simple as that.

I agree with you that “Precious resources (Examiner hours at the EPO, for example) should be conserved whenever possible, and only expended when necessary”, but this cannot dispense the EPO to abide by the EPC. The day Art 84 is deleted or amended, I will certainly review my position.