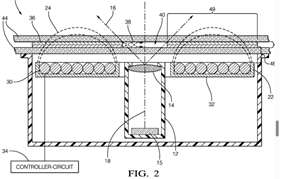

EP 3 672 361 B1 relates to an induction heating device that clears condensation from a viewing window of a camera.

Claim1 starts with: “A windshield (20) or a cover-glass…..”

Brief outline of the case

The OD considered that the patent as granted was infringing Art 123(2).

The patent was maintained according an AR in which the alternative “cover glass” was deleted from claim 1. The opponent appealed.

The board set aside the OD’s decision and maintained the patent as granted.

The case is interesting in that the board held that Art 123(2) was not infringed, and the objection raised by the opponent was at best an objection of lack of sufficiency, a ground of opposition never raised by the opponent.

The proprietor’s point of view

The proprietor argued, that windshield and cover-glass fulfil similar functions and are synonyms and interchangeable can thus not be shared.

The OD’s decision

The OD held that the patent extended beyond the content of the application as filed, because the latter failed to provide a direct and unambiguous basis for the second branch of the claim, that is for the combination of a cover-glass with a heating device.

The OD held that the application was strictly limited to embodiments, in which the heating device was associated with a windshield.

The few passages of the description that referred to a cover-glass with a heating device were seen as relating to background information, or as being insufficient to establish a clear relationship between the cover-glass and the heating device.

In the absence of such a clear relationship, the OD held that the statement in the application regarding the suitability of the heating device for a cover-glass was not a sufficient basis for a claim directed to this combination.

The OD did not share the proprietor’s view that the terms cover-glass and windshield were used as synonyms in the application.

The board’s decision

The board did not agree that windshield and cover glass are synonyms and interchangeable.

For the board, the application, as a whole, nevertheless contained a direct and unambiguous basis for the claimed combination of a cover-glass with a heating device, as defined in granted claim 1.

The application associates windshield with a vehicle. Cover-glass, as commonly understood, applies to items intended to cover an object or space, and, in the absence of any more specific indication, means a cover for a camera lens that is in the optical path between the lens and the camera’s scene.

The OD based their findings on the observation that the originally filed description was completely silent about the relationship of the heating device with any cover-glass.

More specifically, the OD held that, the originally filed application did not disclose, directly and unambiguously, the feature of the secondary induction coil being in direct contact with the cover-glass.

In the board’s judgment, the lack of detail regarding the relationship between the cover-glass and the heating device, as relied upon by the OD, does not mean that the claimed combination has no basis in the application as filed.

Any lack of detail regarding this aspect of the invention might be relevant for the question of sufficiency of disclosure, but is without bearing on the question of whether the original disclosure contains a direct and unambiguous basis for the recited combination.

Art 83 on the one hand, and 100(c) and 123(2) on the other, define distinct conditions and are to be treated separately.

The question raised by the opponent as to the, missing or not, relationship between cover-glass and heating element, is not relevant under Art 100(c) or 123(2).

It might be an issue regarding sufficiency of disclosure, but that is a ground that was not raised by the opponent or the OD.

Comments

The opponent thought only of an attack under Art 100(c), but not under Art 100(b).

It is thus no surprise that most opponents bring all grounds under Art 100 when filing an opposition, even realising that some attacks will not be successful.

In the present case, it is however not certain that an attack under Art 100(b) would have been successful.

If an attack under Art 100(b) is successful, it cannot be overcome without ending with added-matter.

If an attack under Art 100(c), the proprietor often sits in an inescapable trap.

Both objections under Art 100(b) and (c) do however render moot any attack for lack of N or IS.

Comments

15 replies on “T 2035/23 – Added subject-matter vs. sufficiency of disclosure”

I do not agree that if an attack under Art 100(b) is successful, it cannot be overcome without ending with added-matter, in general. I would be interested in the basis for this and what case law there is to support the position.

If claim 1 recites an electric a car having a unit for providing electrical energy to the wheels, claim 2 recites that the unit is a battery, and claim 3 recites that the unit is an energy harvesting unit that has 110% efficiency (or anything else clearly insufficient), this can be solved without adding matter.

Is the statement perhaps intended to be limited to independent claims only?

@ Anonymous,

You might not agree with my statement, but I do not see any reason to change it.

I take that in your example claim 1 is an independent claim, and claims 2 and 3 are dependent claims.

One apparent way to overcome the objection under Art 83=Art 100(b), would be to delete claim 3, or alternatively to delete the value 110% in claim 3. However, there must be a corresponding statement in the description. You can as well delete this part of the description.

However, to actually overcome the objection of insufficiency, be it in the description or in the claim, other than by mere deletion, you necessarily have to bring in subject-matter which was not present in the original disclosure.

In my last directorate, we had to deal with mechanical perpetuum mobile. Such applications were rarely refused under Art 83, but much more frequently under Art 123(2). It was actually irrelevant whether the added matter ended in a claim or in the description.

Hence my conclusion: an objection under Art 83=Art 100(b) cannot be overcome without adding matter. This stance is valid whether the objection is raised against an independent or a dependent claim.

I would also like to draw your attention to the fact that it depends whether an effect is claimed or not.

If the effect is claimed, but cannot be achieved, then the objection is that of lack of sufficiency. If the effect is not claimed but cannot be achieved in view of the description, i.e. is part of the problem to be solved, then the objection is that of lack of inventive step. I refer to G 1/03, Reasons 2.5.2, or T 2001/12, Headnote.

I am reading the thread and trying to read the mind of Anonymous. My guess is that he sees his claims 1 and 2 as unassailable under Art 83 but claim 3 as a dead duck under Art 83. Therefore, he posits, simply deleting claim 3 (and the corresponding text in the description) removes the Art 83 issue without adding subject matter. Ergo, your proposition fails!

But his hypothetical supposes that the Art 83 attack is levelled, not against the subject matter of the patent application as such but, rather, against some optional detail in one or other of the disclosed embodiments, a detail so unimportant that it can happily be expunged from the description and claims without any effect on the thrust of the patent application as such. I think that scenario falls short of disproving your contention, that a lack of sufficiency cannot be cured without adding matter.

Dear Max Drei,

Thanks for your comments.

When teaching about sufficiency, I give the following example in order to explain the difference between objections under Art 83 and Art 84.

When essential features are missing in the claim, but disclosed in the original specification, then the objection is an objection under Art 84, which can be overcome, by bringing in the claim, the missing features. As they have been originally disclosed, there is no added matter involved.

When essential features are missing in the claim, but are as well missing in the original specification, then the objection is an objection under Art 83, which cannot be cured without adding matter.

If there is a problem with dependent claim 3, as suggested by “Anonymous”, the only way to assess whether the disclosure is sufficient, is to see whether the original disclosure allows to fill the gap. In the absence of any corresponding features in the original specification, the lack of sufficiency cannot be cured without adding matter.

In the situation envisaged by “Anonymous”, it might well be possible to delete claim 3 and the corresponding part of the description, but in order to assess the lack of sufficiency, it is necessary to check whether added matter has to be brought in the original specification in oder to overcome the lack of sufficiency.

Whether in an independent or in a dependent claim, an objection of lack of sufficiency cannot be cured without adding matter. A following deletion in the specification and the claims is therefore irrelevant.

You understood what I meant. I hope it is now clear enough for “Anonymous”.

In the example given, if claim 2 is added to claim 1 and claim 3 is deleted, then the claims no longer cover any embodiments which are insufficiently disclosed and no matter is added. The amended claims relate to an electric a car having a battery for providing electrical energy to the wheels, and do not recite or even cover the insufficiently disclosed energy harvesting unit. The portions of the description relating to the energy harvesting unit can be deleted or marked prominently as not being the invention, it does not matter which approach is taken.

Ergo, the ground under Art. 100b would have succeeded but an amendment was found to avoid revocation. I hope it is now clear enough.

Anon, I have seen your most recent reply and I think I understand your hypothetical as follows.

My claim 1 is directed to subject matter notoriously old. So too my dependent claim 2. Claim 3, dependent on claim 2, is directed to ineligible subject matter, insufficiently disclosed.

Well, of course, one can excise the ineligible matter to avoid the objection to invalid claim 3. But what does that leave you with? A specification disclosing nothing but notoriously old matter, followed by claims to it. This is not a good way to invalidate the proposition of Daniel Thomas that there is a way to get to grant by deleting matter insufficiently disclosed without having to add new matter.

What is the point of your hypothetical except to try and score a debating point? Why should we all waste any more time on it?

Claim 1 could have some other feature in it that confers inventive step and which is sufficiently disclosed. The point was merely to question the accuracy of the blanket statement “If an attack under Art 100(b) is successful, it cannot be overcome without ending with added-matter” was actually correct. Isn’t accuracy important in this industry? I am sorry that you feel your time has been wasted.

And it seems that the answer is clearly no, because an attack under Art 100(b) can be successful and can end with a dependent claim being deleted and another dependent claim being added to the independent claims, with no objection under Art 123(2). To borrow the phraseology used elsewhere in this thread, the statement in the original post is plainly obviously incorrect and misleading.

@ Anonymous,

In your last reply, you are actually pushing a discussion which clearly leads to nowhere, as suggested by Max Drei.

Unless you push me to it, I will not any longer waste my time to reply to your misleading and unnecessary comments. This is my last reply.

The situation you describe is the same as when dependent claim 3 would be not allowable for added matter. One way of coming out of the problem is then manifestly to delete claim 3. However, before having to decide that claim 3 has to be deleted, and comprises adding matter, you have to apply the gold standard, i.e. to check whether the claimed subject-matter is directly and unambiguously derivable from the original disclosure.

The same applies if the subject-matter of dependent claim 3 lacks sufficiency. Before deciding to delete the claim, you have to check whether the subject-matter of claim 3 is indeed lacking sufficiency. And to determine this, a good way is to check if added matter would be needed in order to overcome the objection. When adding matter is the only way to overcome the objection, then the objection is clearly a lack of sufficiency.

In both cases, the objection can indeed be overcome by deleting the claim, but this does not dispense you to check whether the objection is correct or not. I have never disputed the fact that in some situations, an objection can be overcome by deletion of a claim.

My message has never been to find a way to overcome an objection, but to determine whether there is an objection, and in the present case a lack of sufficiency.

If you read the statement in the original post with a mind willing to understand it, and to not willingly misunderstand it, then it is anything but plainly obviously incorrect and misleading. Your comments are misleading as they do not go to core of the problem. Before avoiding a problem, you have to be in the position to determine that there is a problem.

Deleting claims has never been at stake at at all. I repeat that, before deleting a claim, you have to find good reasons to delete it. My aim was to show a practical way to do so in case of a lack of sufficiency. If in case of dependent claim 3 you need to add matter in order to overcome a lack of sufficiency, then the absence of features in the claim leads invariably to a lack of sufficiency.

When the lack of sufficiency lies in an independent claim, then there is often little possibility to save your application/patent. If you have other independent claims, than you can also delete the claim suffering from a lack of sufficiency.

To come back to your first comment, the way to assess lack of sufficiency I propose, applies to all types of claims, dependent or independent.

If you do not understand this, you should not be active in IP.

Ergo, has the penny now dropped?

As Daniel Thomas has just now clarified, one way to respond to an objection to dependent claim 3 is to delete claim 3. Is that “overcoming” the objection to claim 3 though? Seems to me it is more like NOT overcoming the objection but, instead, bowing to its overwhelming force.

More interesting is the point made by FH, that invoking what is implicit or otherwise within the common general knowledge of the skilled addressee might succeed in overcoming the objection. But should we not be confining our debate to objections under Art 83 EPC that are well-founded?

As you say, we should all strive to be unambiguously clear and accurate in everything we write.

@Anonymous

Thank you for your question based on a scenario of claims 1-3 with dependent claims 2 and 3 drawn to different embodiments for the energy supply in an electric car.

I can cite a decision which exactly matches your scenario. This is T 1173/00 (Alstom vs ABB) relating to a transformer with high-temperature supraconductor for locomotives. This decision was published in the OJ EPO 2004-1. I was personally involved in this case (I was at that time Alstom’s IP manager).

In ABB’s patent in suit EP590546, dependent claim 2 mentioned a high-temperature supraconductor (ie using liquid nitrogen coolant). High-temperature supraconductors suitable for locomotive transformers (very big size, 1-6 MVA range) were not available at the priority date and this was our argument to show unsufficiency. The Board found persuasive the expert evidence we submitted to define the CGK at the priority date and revoked not just claim 2 but the patent as a whole, based on the reasoning that the use of high-temperature supraconductors, while mentioned in a dependent claim, was clearly critical for the purpose presented in the description. This decision suggests that in your scenario, the deletion of claim 3 may not be sufficient to avoid the revocation of claim 1, depending on whether the use of a energy harvesting unit is to be considered critical in the light of the description.

Another significant aspect of the decision was the assessment of the CGK, a key issue in the UK approach, which is typically difficult. The expert evidence was a written report. It was authored by a scientist recognised as an expert in the field of supraconductors. Very importantly, the expert’s assessment of the CGK was supported by a number of publications, some being earlier surveys of the state of the art authored by the expert.

I think it is an interesting case as to which kind of expert evidence can be convincing to the deciding body. The patent owner’s argument that the report was biased for the sole reason that it had been commissioned by the opponent was dismissed by the Board.

Turning to your specific question, I think it is correct to state that a sufficiency attack, if successful, cannot be cured without violating Art 123(2), and I agree with Mr Thomas on that.

This is one of the reasons which explain that during examination, the EPO has paid scant attention to the sufficiency requirement, except in certain fields, and it was left to third parties to raise the issue through opposition or Art 115 observations. A sufficiency objection being a potentially lethal weapon, there has been the idea that it could be considered applicant-unfriendly.and bad for the optics.

Mr Hagel,

I never quoted T 1173/00 in my presentations on lack of sufficiency, but I used it as an exercise for the participants to decide whether sufficiency was given or not. In the exercise claim 2 was also dealt with. To me T 1173/00 is a good example of a lack of sufficiency which is plainly apparent for a dependent claim, but, as you say, the lack of sufficiency also applied to claim 1.

High-temperature superconductors suitable for locomotive transformers were not available at the priority date and this was enough to show a lack of sufficiency. The board when even one step further and added the following in headnote 2:

“If the disclosure of an invention is insufficient, it is not necessary to know whether it was objectively impossible to remedy this deficiency at the priority date, i.e. to determine whether no one could have obtained the technical effect sought and claimed. What matters is whether the invention was sufficiently fully disclosed that a person of ordinary skill in the art, familiar with the patent and using his general knowledge, could have carried it out at the priority date”.

What I have proposed is a tool, which in my experience is useful. If, in order to become sufficient, the insufficient disclosure needs to be completed with features not originally filed, then sufficiency is manifestly lacking. This is always the case when dealing with perpetuum mobile.

The question of CGK is an interesting one. In a lots of oppositions it is the opponent which brings into the procedure documents showing CGK, although I know for a fact that lots of documents showing CGK are available on the EPO’s premises. Those documents do not seem to be present in the search files, and hence very rarely mentioned in search reports established by the EPO. Here the quality of the search could be improved in this respect.

I personally doubt that not raising objections of lack of sufficiency during examination is due to the idea that it could be considered applicant-unfriendly and bad for the optics. It is rather due to the level of proof required.

Without facts supported by rebuttable evidence, it is extremely difficult for an ED to raise during examination an objection of lack of sufficiency. This is only possible if the lack of sufficiency is manifest, e.g. a perpetuum mobile. The EPO does not have labs to carry out experiments.

I do however agree that in case of parameters, the absence of a measurement method for a parameter, in the original disclosure, especially for an unusual parameter, should in lots of cases end with an objection of lack of sufficiency. The absence of a measurement method is not a mere question of lack of clarity. If a method has to be added to the original disclosure, then the problem is clearly a lack of sufficiency. It is however easier to evacuate the problem in opposition in view of G 3/14.

The same applies if a norm is cited in a specification or even in a claim. For instance, some tests for polymers are defined in norms. Then the date of the norm is an important information and cannot be added after filing, as norms can even change between priority or filing date, e.g. T 881/02 or T 783/05.

I agree in general with the conclusion that an Art 83 objection cannot be overcome without the addition of new matter but there are exceptions : if the missing information is implicit from the application; and if the applicant can provide evidence of CGK relevant to the art of the skilled person to show compliance with Art 83.

Another remark : I do not think Art 83 objections should be limited to informarion related to “essential features” of the claims. It happens that claims include features which are not clearly essential

Mr Hagel,

What you are stating first is plainly obvious, and hence unnecessary.

According to the Guidelines, F-II-4.1, the skilled person when assessing sufficiency of

disclosure is considered to be the ordinary practitioner aware of

– the teaching of the application itself

– the references in the application

– common general knowledge in the art at the date of filing the application

Your second remark is as well unnecessary, not to say misleading. I gave the example of “essential features” to be missing in order to compare when an objection under Art 84 or under Art 83 applies.

Any feature contained in an independent claim is, as a matter of principle, essential.

Any deletion of features in an independent claim can lead to problems of added matter in examination or extension of scope in opposition.

Die Anmeldung enthält als Ganzes dennoch eine direkte und unmissverständliche Grundlage für die beanspruchte Kombination einer Abdeckscheibe mit einer Heizeinrichtung, wie in Anspruch 1 der erteilten Patentschrift definiert.Regard S2 Akuntansi

@ Administrasi Bisnis

Without a more detailed argumentation, I fear that your point of view appears no more than a mere allegation.