The present invention generally relates to an optical system for projecting one or more synthetic optical images, which demonstrates improved resistance to optically degrading external effects.

Brief outline of the case

The proprietor appealed the revocation of its patent.

The board confirmed that claim 1 as granted contravened Art 123(2)

Admissible AR were not allowable, either as they contravened Art 123(2) or lacked IS over D3=WO 2007/0769523 + D2=US 7 333 268.

The revocation was thus confirmed.

The case is interesting as it deals with arguing inventive step or the lack of it when it comes to combining documents.

We will consider AR2, labelled “Main Request (b)“.

The OTP defined by the OD

The OD found that starting from document D3 as the closest prior art, the OTP could be regarded as finding an alternative for the image icons with increased resolution.

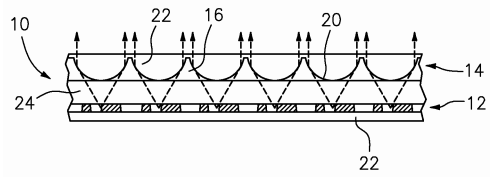

The relevant figure of D3:

The opponent’s position

The opponent agreed to the formulation of the OTP.

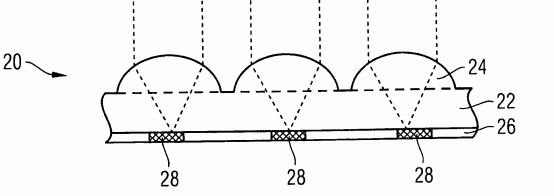

The opponent (and the OD) argued that starting from document D3, the person skilled in the art attempting to solve the objective problem would turn to document D2 and learn that forming the image icons as voids or recesses has the “benefit of almost unlimited spatial resolution” (see column 16, lines 7 to 14, and Figure 7c).

Figure 7c of D2

The skilled person would thus be motivated to replace the printed structures of D3 with the microstructured voids of Figure 7c of D2 (feature 1m).

In addition, D2 also disclosed (see column 26, lines 45 to 54, and claims 65 and 66 ) that such recesses of a microstructure preferably have a depth of 0.5 to 8 µm. (feature 1n).

The proprietor’s position

The proprietor agreed with the OTP, but argued that in addition, amended feature 1k’ improved the protection of the image icon focusing elements against environmental influences and also against counterfeiting.

For the proprietor, the disclosure of D3 was merely a generic disclosure of a protective layer, without the specific properties of the layer as defined in feature 1k’ of claim 1.

These properties of the protective layer were not implicitly disclosed in D3 either, since in the case of concave lenses, the interstitial spaces were formed by elevated structures between the focusing elements and it would be sufficient for the protective layer to cover only the focusing elements, i.e. to fill only the valleys forming the concave lenses.

Furthermore, an intermediate layer between the focusing elements and the protective layer was not ruled out by the disclosure of D3

In conclusion, the mere disclosure of a layer protecting the concave focusing elements was “neither [a] direct nor unambiguous disclosure for the interstitial spaces […] being also covered by the protective layer disclosed by document D3”.

The proprietor argued that in strict application of the problem-solution approach (PSA), the skilled person combining the teaching of document D3 with that of D2 would arrive in a straightforward manner only at the provision of a protective layer over the focusing elements (as known from D3).

However, this was not what was claimed because there was no indication in either D2 or D3 or a combination thereof to use a protective layer which covers the focusing elements and also fills the interstitial spaces between them. Arriving at this feature clearly involved hindsight.

The proprietor further argued that instead of applying the established PSA, the opponent and the opposition division’s line of argument was that when starting from the combination of D3 with D2, the skilled person would be confronted with the task of selecting a material for the sealing material layer for the image icons and that it would then be obvious to the person skilled in the art to choose a material that was already used in the system for the same purpose.

However, this was not what the PSA required and was detrimental to the evaluation of the presence of an inventive step according to established case law.

With respect to a combination of two documents, the proprietor argued that for some of the claimed features the documents provided no “direct and unambiguous disclosure” and that “[a]ccording to the PSA, if there is any remaining feature not taught by this combination, the subject-matter claimed has to be acknowledged to involve an inventive step”.

The board’s position

The board agreed with the OTP as formulated by the OD.

The board did not agree with the application of the PSA done by the proprietor.

In the fourth and final stage of the PSA (see Case Law of the Boards of Appeal, 2020 edition, I.D.2) it is considered “whether or not the claimed solution, starting from the closest prior art and the objective technical problem, would have been obvious to the skilled person”. This stage is most closely related to the requirement of Art 56, according to which “[a]n invention shall be considered as involving an inventive step if, having regard to the state of the art, it is not obvious to a person skilled in the art”.

Since Art 56 and the final stage of the PSA both consider what is obvious to a person skilled in the art, an inventive step cannot be acknowledged solely on the finding that the claimed subject-matter is not directly and unambiguously disclosed from the combination of two documents.

In other words, when considering the question of whether an invention is obvious starting from a document representing the closest prior art in combination with another document, it is not the mere sum of the teachings of these two documents that has to be considered; the skilled person’s common general knowledge and skills must also be taken into account when combining the two documents.

Application to the present case

In the case at hand, D3 does not disclose that the protective layer, which, according to claim 1, is represented by the second material, fills interstitial spaces between and covers the focusing elements and forms a distinct interface between the first and the second materials, as discussed above.

However, the board agreed with the opponent that for the person skilled in the art considering the specific implementation of the protective layer taught by D3 it would be obvious not only to fill the concave parts of the lenses with material but also to cover the spaces between them in order to provide sufficient protection for the focusing elements. Otherwise, the boundaries between the filled portions and the protrusions would act as points of attack for harmful environmental conditions, as would be readily apparent to the skilled person.

In addition, in view of the required relationship between the refractive indices, it would be clear to the skilled person that the protective layer would necessarily have to be formed without an additional intermediate layer and would therefore also form a distinct interface with the first material.

Hence the subject-matter of claim 1 was lacking IS in view of D3 + D2.

Comments

This decision is highly interesting as it makes, once more, clear that assessing IS does not stop at the mere addition of the teaching of two documents.

Similarly, when combining the teachings of two documents, there is no need for a pointer from one to the other. In real life, i.e. outside the EQE, this would not likely be the case.

When combining the teachings of two documents, the person skilled in the art can fill in the gaps with its common general knowledge.

The limit of this action is when it comes to hindsight, or when the gaps are wide.

On the procedure

The patent should not have been granted in the form it was, as claim 1 contravened Art 123(2).

Doubts about the search are also permitted. The ISR established by the EPO mentioned 5 documents of category X, as well as a lack of unity. Neither D3 nor D2 were mentioned on the ISR.

Claim 1 of AR2=MR(b), is necessarily limited with respect to the granted claims. D3 and D2 were thus relevant at the time of the original search and should have been found and mentioned in the ISR. https://www.epo.org/en/boards-of-appeal/decisions/t211246eu1

Comments

2 replies on “T 1246/21 – Assessing IS = more than just combining documents – Common general knowledge also plays a role”

Interesting indeed, Daniel. Thanks for flagging it up for review.

The Decision and your report prompted me to think about the difference between what the skilled person could or would do. Once we have pinned down the prior art starting point and the OTP, searched for and found D2, what remains is the enquiry, NOT what the skilled person could have done next but, rather, what the skilled person would have done next, to solve the OTP. Being skilled, the person would have aimed at creating something that “works”, something that has adequate performance. So, in building the device, the skilled person would surely do what they already know is needed, to get a satifactory performance out of the device.

Looking at it another way, the person, being skilled, in constructing a device, does NOT deliberately do things that they know will harm performance of the device.

That in turn reminds me of the Art 83 enquiry. It is nearly always possible to conceive of a device that fulfills all the features of claim 1 but nevertheless doesn’t “work”. But that’s not enough to succeed with the Art 83 attack, is it? Perhaps because allocating to the skilled person a will NOT to succeed is unfair to the Applicant and not the way to operate a patent system that promotes technical progress by i) granting patents for inventive matter while ii) blocking patents for everything that, for the skilled person, was already obvious to do.

Dear Max Drei,

Thanks for your comments.

For the opponent, the skilled person is hyper intelligent and it would combine everything possible.

For the proprietor, the person skilled in the art is thick as two planks and either it would not combine anything, or if it would do, there would still be gaps. The latter position is that adopted by the proprietor in the case at hand.

The present decision shows that the truth is somewhere in between.

I am not sure that it is nearly always possible to conceive of a device that fulfils all the features of claim 1 but nevertheless doesn’t “work”. Even if it would be so, what good would it be?

On the other hand, contrary to the old German doctrine, there is no need for an invention to be better than what was already known. In this respect there was the notion of “Erfindungshöhe” or inventive height.

At the EPO, inventive step is given as soon as the solution of a technical problem is not obvious to the skilled person. Whether it is better than what already exists is actually irrelevant. However, a patent is in principle covering an item which has a commercial value. It is difficult to see that what represents a regression over what exists, would have any chance on the market.

I would consider that patented items ending on the market, can be compared to the emerged part of an iceberg. Patents having stayed in cupboards are represented by the immersed part of the iceberg. But all in all, patents promote technical progress.