EP 1 825 720 B1 relates to a distributed intelligence multi-ballast lighting system.

Brief outline of the case

The patent was maintained according to AR2.

Proprietor and opponent appealed this decision.

Although the patent had lapsed in all designated states. the opponent requested continuation of the opposition proceedings.

During the OP the proprietor withdrew its appeal.

The patent was revoked for lack of clarity as well as for added subject-matter. In its communication under Art 15(1) RPBA, the board had objected clarity and added matter of the MR filed in reply to the opposition.

At stake are the formulations “ the ballast coupled directly to a photosensor (22)” in method claim 1, and “the ballast coupled directly to a photosensor (22) for receiving electronic photosensor information” in apparatus claim 8.

The OD’s position

The OD acknowledged that there was no verbatim disclosure in the application as filed for the feature of the ballast being “coupled directly” to a photosensor as recited in claims 1 and 8.

The OD stressed that the phrase “directly coupled to” implied a communication without intermediate devices. Such a coupling was disclosed, for example, in paragraphs [0054], [0057], [0059], and [0129] of the application as filed.

Particular reference was made to paragraph [0129] which stated that the “ballast obtains a raw photosensor reading“. In the OD’s view, this implied that no further intermediate devices were present.

The board’s communication under Art 15(1) RPBA

For the bord, it was unclear whether the term “coupled directly” simply implied the absence of intermediate devices, as put forward.

The terms are inherently ambiguous and may also have a spatial meaning, simply requiring that the ballast be in physical contact with the photosensor.

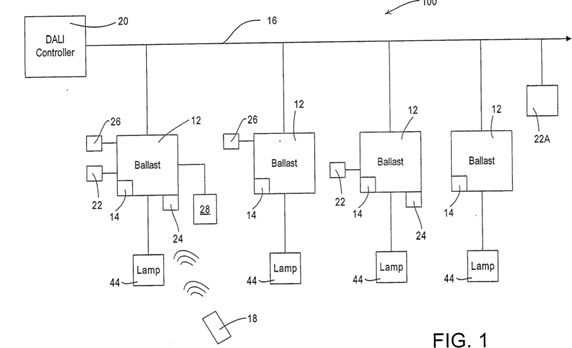

However, while certain ballasts of the invention disclose them as receiving photosensor readings from remote photosensors on other ballasts, the description also discloses combinations of photosensor and ballasts that can operate independently (Figure 1), thus adding to the confusion.

AR 2 differs from the MR in that claim 8 contains the further indication that the broadcasting is “via the communication port“. Independent claims 1 and 8 of AR 2 in common that they include the terms “coupled directly to” and refer to the notion of “out of box mode representing a default condition“.

The board further noted that the various interpretations relied upon by the parties illustrate the broad spectrum of meanings associable with “coupled directly“.

For the board, the phrase “coupled directly to” must be construed in view of the function to be achieved by this feature under the circumstances. Taking account of the various configurations for coupling ballasts to photocell sensors in the original disclosure, it appears that a distinction is made between ballasts obtaining their information from remote sensors and those which are autonomous in that they rely on their own photocell sensors.

From a functional point of view, the feature regarding the location of the photosensor in contact with the ballast does not appear to be essential in this context and does not permit a limitation of to this particular aspect.

This latter finding confirmed the view that no clear meaning can be associated to the terms “coupled directly“.

As far as AR2 is concerned, the board considered that the references to an out-of-box mode and to a default configuration do not contradict one another.

The reference in the claims to these two concepts does not permit identification, in any particular ballast, of whether the operating method corresponds to the recited features which appear thus to be deprived of any clear meaning in the context of the invention. Although technically understandable, the terms used appear to be without effect on the claim’s understanding contrary to Art 84.

The board’s decision

As the proprietor withdrew its appeal, the objections against the then pending MR about the terms “coupled directly” in claims 1 and 8 of AR 2 were unclear in the context of the patent specification. Other features define added subject-matter, contrary to Art 123(2).

Comments

The present decision reminds us that an an expression like “coupled directly” can nevertheless be unclear.

Directly coupled

Only In Fig 1 as filed there is a direct connection to be seen between the ballast and the sensor, but this does by no mean imply that it is actually a direct connection. The only direct connection is a connection to a processor which itself acts on the ballast.

Since ballasts can receive inputs from remote sensors it is difficult to consider that the sensors are “directly coupled to the ballast”.

On the procedure

The application was filed on 07.12.2005.

The request for entry into the European phase was filed on 14.06.2007.

A first communication from the Examining Division was issued on 07.10.2008 merely referring to an objection of lack of unity raised in the IPER established by the USPTO.

In reply to this communication, the applicant filed new claims. The amendment “coupled directly to” was indicated in a marked up copy of the claim. This was apparently overseen by the ED.

The communication under R 71(3) was issued on 22.02.2017. The mention of grant is dated 14.02.2018.

No wonder that after the application being idle for such a long time, the patent had lapsed in all designated states during appeal.

A nice case of a submarine application.

Not only examination went wrong, but opposition was not better.

Comments

7 replies on “T 219/21 – “Coupled directly” can be unclear and lead to an objection under Art 84”

In the UK, one learns in the first weeks as a patent attorney trainee that adjectives are inherently unclear and so should be avoided when drafting a patent claim. The same applies to adverbs….obviously.

On the specific word here “directly” the Gold Standard formulation comes to mind. Is that unclear too? Or is its “directly” a convenient way to inject into the Gold Standard enough “wiggle room” to allow tribunals always to get to an outcome that serves the interests of justice between the parties?

Dear Max Drei,

In can agree with you that adjectives or adverbs are inherently unclear and should be avoided when drafting a patent claim.

But sometimes they cannot be avoided.

On the other hand, to me there is nothing unclear in the glorious sentence: “directly and unambiguously derivable”!

Case law on novelty or added matter does not allow any wriggle room. At least at the EPO.

Whilst the UPC seems to be reluctant, not to say against, the PSA, when looking at decisions on added matter, the notion of “directly and unambiguously derivable” is to be found regularly.

I have difficulties in finding that “directly” could give wriggle room when interpreting a claim. If some device is “directly” coupled to another one, be it mechanically or electrically, it does not mean that there is anything between the two but a direct mechanical or electrical coupling(=a wire). “Direct” coupling does not cohabitate well with coupling “via” something else, be it mechanic or electric.

“Coupled” on its own might also be unclear, and quite often it ends up as well with an objection of added matter.

Enjoyed reading your reply, Daniel. No quarrel with your choice of word “glorious”.

We could discuss for hours reasons why various courts seem to be as reluctant as ever, to go “all in” to the EPO’s problem-solution approach to obviousness. My sense is that when courts consider obviousness, these days, they increasingly find an EPO-PSA analysis helpful but nevertheless are careful to avoid acknowledging any debt they have, to EPO-PSA, as a way of helping them get to the right result. I mean, how can a mere Patent Office adjudicate a core legal concept more sure-footedly than a court finding itself doing it at the end of a money-no-object, bitterly fought, inter Partes civil dispute?

Dear Max Drei,

I have recently been at a seminar in which various decisions of the UPC, on substantive matters, like extension of object and IS, as well as purely procedural matters, were discussed and compared with the way those topics are dealt with by the EPO and German courts.

It is based from what I heard at this seminar, that I made my comment on the use of “directly and unambiguously derivable” at the UPC. It is still early days, but “DAUD” seems to get more and more used at last in first instance. We will have to see if the CoA goes along the same line. In spite of any possible interpretations of the claims, it is a very simple way to determine whether we have added matter or not.

When you see that most of the cases of revocation or counterclaims for revocation are filed in German local divisions and in the Munich Section of the CD, it appears manifest that the German way of thinking is making inroads at the UPC. This is also comforted by the few decisions of the CoA in this matter. The PSA appears definitely not to be the UPC’s cup of tea.

A first aspect which appears to play a role in not wanting to go along with the PSA at the UPC, is the famous “not invented here”. I will not dwell on it.

A second aspect, which is linked with the systematic interpretation of the claim, and which I take from last week’s discussion about the necessity of always interpreting the claim in the light of the description, is the lack of technical knowledge of civil law judges. It is only if they understand what is claimed, hence have interpreted the claim, that they are prepared to take a decision. This was clearly explained by the former German judge, who further welcomed technical judges in German civil courts.

This is also the reason why the notion of OTP is foreign to the UPC. In order to show a lack of IS, the skilled person, which have always to be defined beforehand, is to find in the prior art an incentive to come to the claimed solution, whilst sticking to the problem mentioned in the application/patent. At the EPO, it is very rare that the skilled person is at all defined. This is due to the fact that, even at the BA level, there are always two TQJs acting.

It was also interesting to see that the in the decision of 14.01.2025 of the LD Düsseldorf, UPC_CFI_16/2024 – Ortovox v. Mammut, the LD concluded to the full validity of the patent and to full infringement.

However, the same patent, with the same prior art, was considered invalid by the Swiss Federal Patent Court. It will be interesting to see what will happen in appeal for both cases. The LD Düsseldorf sat in a composition of 3 LQJ and 1 TQJ, whereas the Swiss Federal Patent Court sat in a composition of 1 LQJ and 2 TQJ, similar to the composition of an EPO BA. In my opinion, the Swiss decision is much better argued than the UPC decision. The LD Düsseldorf decision is very patentee friendly.

A second decision was discussed at this seminar. It’s the decision of the CD Section Paris, UPC_CFI_308/2023 – NJOY v. VMR, 27.11.2024. The CD Section Paris , concluded to the invalidity of the patent, for reasons which are very difficult to follow, and actually very hostile towards the patentee.

This gives me to think that the absence of a substantive revision instance at the UPC bears a great danger for parties.

I am enjoying this exchange, Daniel. Your knowledge base is fully up-to-date whereas mine comes from decades ago, from litigation in England and at the EPO. As you point out, tribunals at the EPO don’t need to spend much valuable time crafting a definition of the specific person skilled in the art whereas courts lacking “technical judges” do. Further, at least in England, judges learn with their mother’s milk not to decide based on their own technical knowledge but, rather, exclusively on the evidence laid before them, including the question what was the state of the art and what was the state of general knowledge of the skilled person.

Methinks it suits the litigators, to argue before a non-technical court. There is so much more to argue, so much more to explain to the court, so many more hours one finds necessary to bill to the client.

Methinks the quality of decision-making at the EPO might owe something to the fact that the litigators struggled until recently to get their foot into the market sector “disputed proceedings at the EPO”. For decades, the debate was between specialist technical judges and equally specialised technically expert advocates. The arrival of the UPC, and its developing case law generated by tyro infant largely non-technical courts is, I suspect, a source of great delight for the litigation community (and probably also its deep-pocketed international corporate client base).

It’s a cliche, but investor confidence, and therefore technical progress and therefore individual prosperity, depends on legal certainty. I doubt it is a good idea to nurture those parts of society which thrive on legal uncertainty.

Dear Max Drei,

I am also enjoying this exchange. I might have my knowledge more present than you have it, but I think we are on the same wavelength.

At the various conferences on the UPC held at the EPO before it came into place, it became rapidly clear to me that lawyer’s firms, and especially large Anglo-Saxon lawyer firms and some European ones, wanted to take back what they had to give up to professional representatives before the EPO when it came to validity of patents.

It even happened at one of those conferences, that a well-known lawyer, who later had a great influence in the design of the deontology rules for UPC TQJs, made it absolutely clear that he, let’s say, “disliked” technical judges. I know this not by hearsay, but this person stood next to me when it uttered his deep dislike of technical judges.

You are thus right to think that the litigators struggled until recently to get their foot into the market sector “disputed proceedings at the EPO”. For decades, the debate was between specialist technical judges and equally specialised technically expert advocates=professional representatives. It was very rare that a “pure” lawyer actually represented a party in opposition and opposition appeal procedures.

It can therefore be considered that the arrival of the UPC, and its developing case law generated by largely non-technical courts is, is indeed a source of great delight for the litigation community, and especially its deep-pocketed international corporate client base.

It was one part of the deal of the UPC to accept TQJs, but when looking at the composition of the UPC panels, it was made sure that TQJs were in the minority and in case of different opinions, that the opinion of the LQJs will prevail. I was present at some hearings before the UPC in Munich, and I have never seen that the TQJ played a big role. When looking at some decisions of the UPC one wonders if the TQJ has at all been active.

It should also not been forgotten that the UPC RoP were concocted by a small self-co-opted group of lawyers active in the same firms. When deciding that the time limits at the UPC would be very short, it became very clear to me that time pressure would be a cost increasing factor. Not only a multi-national litigation would allow to increase fees, but also the time pressure coming with it was an aggravating factor. This is a comment I have heard at many conferences about the UPC.

It should also not be forgotten that on the hand, less than a third of granted patents are held by proprietors residing outside the UPC contracting states, whereby more than half of granted patents are held by non-European owners. On the other hand, the UPC has opened a single door for litigation for all these non-European patent owners. I fail to see how this could be beneficial to European industry in general and European SMEs in particular.

Daniel, thanks for all that about technical judges. Quite an eye-opener for me. But while on the “international” topic, and who benefits from the UPC, one might look across the Atlantic Ocean to see how patents are litigated in the USA. Early in my long career I remember being startled when one litigator averred that no foreign claimant had ever won a big patent litigation case in the USA.

The US Americans have always had a keen sense of “America First” but you would never have known it because, until recently, they were very discreet and reticent about it. The current Vice President’s opinion is that Western Europe has become effete, complacent, indeed dying on its feet, a carcase on which the world’s Great Powers are gorging themselves.

One might think, not just the world’s Great Powers but also the world’s largest international law firms.