EP 3 113 515 B1 relates to hearing devices, and in particular to hearing devices security.

Brief outline of the case

The opposition was rejected and the opponent appealed.

The board revoked the patent for lack of IS.

The case is interesting as the board held that, when there is no technical effect that is credibly derivable from the wording of a claim on the basis of its distinguishing features, there is no IS.

The proprietor further requested remittal and a referral to the EBA of questions relating to the problem-solution approach and the general applicability of G 1/19 and G 2/21. Both requests were rejected.

The proprietor’s point of view

The proprietor submitted that the technical effect of the differentiating features over the CPA was to provide a hearing device that was capable of performing various levels of authentication of a communicating party and received messages as well as deriving keying material for securing communication, e.g. against eavesdropping and modification attacks.

During the OP before the board, this was refined to providing protection against “modification attacks“.

The proprietor further argued that these differentiating features were all causally interrelated and the objections raised were not substantiated beyond a mere reference to the use of definite articles, e.g. “the session” and “the verification”.

The proprietor questioned in general the legal basis for the board’s approach, arguing that the principles of G 1/19 were limited to computer-implemented simulations and that the board should instead have applied the “ab initio implausibility” standard addressed in the referral case underlying G 2/21.

The opponent’s point of view

The opponent argued during the OP before the board, the features of claim 1 as granted constitute a mere aggregation of functionally disconnected security-related jargon, i.e. a collection of “islands of cryptography” without a clear and reliable interrelationship.

The board’s decision

The board was not satisfied that the technical effects mentioned by the proprietor were credibly achieved by the claimed features, especially by the combination of differentiating features, over the whole scope of claim 1 as granted. In particular, the claim was silent on any “levels of authentication” and its features do not necessarily imply protection against attacks such as “eavesdropping” or “modification”.

The board found that, while the use of definite articles may arguably create a linguistic link between the features, it fails to establish a technically meaningful, functional interrelationship that would in fact be required to produce the alleged security effect.

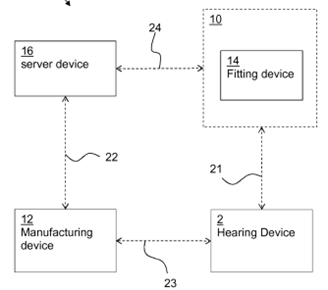

For the purposes of claim construction regarding claim 1 as granted, the board, in accordance with G 1/24, has “consulted” and “referred to” the present patent description and drawings to define how the skilled reader would interpret the claim.

In view of, paragraphs [0001] to [0007] of the description, the technical field of the skilled reader is apparently “hearing device security“.

The skilled reader of claim 1 would however be faced with fundamental ambiguities that militate against the presence of a credible technical effect over the whole scope claimed. In the relevant technical field, terms relating to communication protocols have typically a stable and well-understood meaning.

Therefore, contrary to the approach taken by the proprietor during the OP, these terms are not to be re-interpreted or understood in a more limited way in the light of the specific embodiments of the description, which, in addition, contain subject-matter that is more limited than that claimed.

Due to the deficiencies noted by the board relating to the differentiating features, the asserted technical effects of providing multiple “levels of authentication” or protecting against “modification attacks” were not credibly achieved over the whole scope of claim 1.

The board held that, if there is no technical effect that is credibly derivable from the wording of a claim on the basis of its distinguishing features, it is usually unnecessary to – artificially – formulate an, unsolved, objective technical problem, such as finding an “alternative way to achieve a, non-existent, technical effect”.

In such cases, the distinguishing features simply constitute arbitrary or non-functional modifications of the available prior art which cannot involve any IS.

The proprietor’s attempt to limit the applicability of G 1/19 to the technical field associated with the underlying referral case was incorrect. The board acknowledged that Reasons 82 of G 1/19, by speaking about CI simulations, appeared to support the proprietor’s argument. However, the heading of a section does not limit the legal scope of the principles established therein, particularly when the text itself signals a broader, general applicability. The EBA itself designated its findings in Reasons 82 as a “general principle“.

This “general principle” broached in G 1/19, Reasons 82, confirms that a technical effect must be achieved over the whole scope of a claim to be considered as the basis for the objective technical problem.

While the term “credible” does indeed not appear in G 1/19, the concept is inherent in the requirement that an effect be “at least implied in the claims“, cf. Reasons 124. The term is used explicitly in the same context in the landmark decision T 939/92 (in chmistry), to which G 1/19, Reasons 82, refers.

The assessment of whether an effect is credible is, of course, performed by the deciding body based on the application as filed and the skilled reader’s common general knowledge, a standard which G 2/21, cf. Headnote II, has since affirmed for all technical fields.

Therefore, the board’s approach to assessing whether the alleged technical effect is credibly achieved over the whole scope claimed as adopted by the board is firmly rooted in the established case law of the Boards of Appeal, as summarised and clarified by the Enlarged Board in G 1/19.

The board also quoted various T decisions in support of its point of view as well as the decision of the UPC-CD Munich (UPC 14/2023-Regeneron/Sanofi vs. Amgen) concerning EP 3 666 797 B1.

Comments

In applying G 1/24, the board made clear that the description does not allow to give claims a narrower meaning and cannot be re-interpreted or understood in a more limited way in the light of the specific embodiments in the description.

The board also reminded that considerations of the EBA in G decisions are generally applicable, cf. G 1/19.

One conclusion which comes to mind, is that there was an inconsistency between claims and description. This inconsistency was however not interpreted in favour of the proprietor.

It seems to have become fashionable for boards to quote UPC decisions since the EBA did this in G 1/24.

It is interesting to note that the oppositions filed at the EPO by Sanofi and Regeneron have been rejected by the OD and are presently under appeal (T0716/25), In-person OP have been scheduled from 13.04.2026 till 14.04.2026. The patent has been revoked in first instance by the UPC.

Will we have diverging decisions between the EPO and the UPC? That’s the question!

Comments

6 replies on “T 1465/23 – Arbitrary and non-functional modifications and their effect on IS-Application of G 1/24”

That’s one question, Daniel. But the one in my mind arises because I (by now retired and a hearing aid wearer) personally feel myself lacking in enough relevant technical background knowledge and experience to render a solid Art 56 EPC decision here. Is there any difference between the EPO and the UPC, how the person that decides the Art 56 question pulls together the decisive knowledge and evidence. How big a part are expert witnesses of fact playing in this case, in each involved jurisdiction? If a decisive part, I wonder how much of their evidence has been tested under expert cross-examination?

Or, to put it another way, how much is decided by “technical judges” at the UPC and in the EPO, both at first level and at the level of appeal.

And, in addition, if the knowledge and mindset of the skilled person is decicive to the outcome, how much room at the EPO does a TBA have, to find facts different from those found by the OD?

Dear Max Drei,

What was at stake here is less the hearing aid as such and its working, but establishing a secure communication session between the hearing device and a client/fitting device. The claimed solution is based on a specific authentication protocol. In view of the lengthy discussion in the decision, I find the reasons for revocation convincing.

I am however at a loss to determine what the respective input of a technically qualified members of the board, or UPC technically qualified judges could be.

I would guess that at the EPO boards of appeal, although the decision is signed by the three board members, when it comes to pure technicalities, the legally qualified member will most probably go along with the two technical members. When the case has procedural aspects which become important, I could think that the legally qualified member is playing a more important role. When it comes to interpreting the EPC, like in T 56/21, the legally qualified member has a prominent role in the decision. To illustrate this point, in T 56/21, it was the legally qualified member who was rapporteur.

In a local division of the UPC, cf. Art 8(1-5) UPCA, there are always three LQJ, and in big countries, two of them have the nationality of the country in which the LD sits. In a UPC LD, the TQJ is a kind of add-on drawn from a pool of judges.

He will thus by definition be in the minority. In view of the lack of technical knowledge of LQJ, it is thus necessary to interpret the various claimed features before coming to the decision. The TQJ can help in this process, but in the end, he can be outvoted by the LQJ. Some of the decisions taken by a UPC LD are open to discussion, and this shows that the TQJ might not have been heard as it should have been by the three LQJ.

The composition of a panel of the UPC CD is more comparable with that of an EPO board of appeal, with the big difference that there are always two LQJ and only one TQJ. It could thus appear that the TQJ has a more important role, but the latter can still be outvoted by the two LQJ. Some of the decisions taken by a UPC CD are also open to discussion, and this shows that the TQJ might not have been heard as it should have been by the LQJ.

The situation is similar at the UPC CoA, with always three LQJ and two TQJ. The two TQJ can still be outvoted by the LQJ. Some of the proponents of the UPC have always expressed strong reservations against TQJ and would have preferred not to see them involved at all. This is not an information by hearsay, I heard it with my own ears.

Although hearing of experts is mean of taking evidence under Art 117(1,e) EPC, I cannot remember to have seen an expert opinion requested by the EPO or a board of appeal. In a recent decision, T 1692/23, commented on my blog, the board has refused to appoint an expert. Parties are free to bring an expert opinion in the procedure. This expert opinion will be assessed according to G 2/21. The fact that a former member of the boards is called in as expert for a party is, in general, not well received.

At the UPC, hearing of experts is a mean of taking evidence under Art 53(1,e) UPCA. I would consider that those experts are experts of the parties, since Art 57 UPCA foresees that the UPC might appoint a “court expert”. One wonders why the UPC requires court experts as it has at its disposal a pool of TQJ.

Be it at the EPO or at the UPC, cross-examination of expert opinions like in the UK is apparently not foreseen.

As far as finding facts is concerned, in view of the valid RPBA, finding new facts and evidence does not seem to be the bread and butter of the boards. In examination appeals, it can happen that the board brings in new evidence on its own volition, but this is rather an exception than the rule. I have never seen this happening in opposition appeals. What the boards can do, but it is rare, is to admit in appeal, evidence which has not been admitted in first instance.

What can differ greatly between divisions of first instance and the boards, is a different interpretation of the evidence submitted. This explains that at best 15% of patents are left untouched in appeal after opposition. 40% are revoked and 35% maintained in limited form.

I might have been long, but I wanted to give you a substantiated reply to the various questions you have raised.

Daniel, your detailed reply is very much valued.

You write that at the EPO what can “differ greatly” between the OD and the TBA is the “interpretation” of the evidence of fact that the different tribunals respectively make. No wonder then, that it is worth appealing at the EPO and that everybody does it. For “interpretation” is a very personal and subjective act, is it not?

This subjectivity would explain why so few OD decisions survive unscathed the appeal process. Every judge thinks they “know better” than any of their fellow judges. A high level of self-confidence is vitally important to career success as a judge.

So, at the EPO, it is not like in England, where few cases are appealed. That’s because the appeal instance is not in a position to contradict the lower court on the facts that have been established in evidence under cross-examination, and also because the lower court so rarely gets the law wrong.

It will be interesting to follow how the appeal process at the UPC pans out.

Dear Max Drei,

Thanks for your reply.

It is certainly worth filing an appeal at the EPO, but I would not bring in subjectivity from the side of board members into play. There are cases in which the coin can go on one side or the other, and both situations can be equally defended.

it should not be forgotten that OP are a very dynamic event. I do regularly chair simulated OP, with students at the end of their basic training. In one given year, the patent and the prior art are always the same. The argumentation against and/or in favour of the patent is always different. It can have some resemblance, but is never identical. The requests have also some resemblance but are always different. What is however most noticeable is the way OP go along. It is never the same!

One would think with the same patent and the same prior art, objections and requests should be very close and the OP would be similar, so that the result should be the same. On the contrary, it is always different. This simply show that we are all humans and can be influenced in ways we might not even notice.

The wage of members of an OD or of board members, and judges in general, is set and does not vary with the number of decisions going in one or the other direction.

I would therefore refrain from bringing in subjectivity from the side of the boards of appeal. I don’t think they consider themselves superior or better than examiners. However, when you read some first instance decisions, you can often be surprised with what you come across. I do not blame examiners, they do the best as they can in time they are allocated. It is more the system of forced production/productivity which is to blame.

The real problem at the EPO is that two thirds of the decisions of ODs are set aside by the boards. This is alarming. I am inclined to think that if no more than a quarter to a third of OD’s decisions were set aside, this would correspond to the coin falling on the other side, but the same outcome as in first instance could be justified as well.

The boards members do also have to show a certain performance, if they want to be re-appointed, but they certainly have more time to deal with a case. With the actual proportion of decisions set aside by the boards, it has become a quality problem, but the EPO denies and claims that everything is honky dory. I will say no more.

In view of what I see in opposition at the EPO, I would not be absolutely be certain that I could start an infringement action claiming that my patent is bullet-proof. It is certainly worth thinking of a counterclaim for revocation. A cheaper way than to go to the UPC is to file an opposition.

It will be interesting to see what will happen at the UPC. I have always had reservations towards the fact that the basic fee for a claim or a counterclaim for revocation at the UPC is quasi the double of the basic fee for infringement.

The British system of cross-examination in first instance is not part of the judicial tradition and practice on the Continent.

The side of the road cars travel neither!

Hi Daniel, you write that it is “alarming” that 2 out of 3 OD decisions are set aside by the TBA. I not. To me, it is not a bug but a feature of the system. Give me a written Decision of an OD and I will find good reasons why the TBA should set it aside. The written Decision flags up where in the case the losing side failed to drive home its evidence and arguments. Given a second chance, the losing side will “nail it” on appeal.

Long ago, I used to play a game of squash, once a week, against a colleague. If Wally won last week, I would win this week. And then, Wally would, next week, win again. There is something about losing that drives one on, not to lose twice in a row. And that’s even without factoring in one’s professional reputation, that of one’s law firm, and the possibility that the client will switch to another law firm.

The thing about English cross-examination of the respective technical experts is that the truth comes out. After that, there is no room for a court of appeal to be “influenced in ways we might not even notice”. Rather, the judges of the court of appeal have to work with the facts established in cross-examination by the court below, whether in their bones they agree or not. If you ever get an opportunity to pobserve in a real case how a technical expert witness gets cross-examined in an English courtroom, take it. You would enjoy it, I’m sure.

The downside, of course, is that a full-blown adversarial first instance trial with exhaustive cross-examination, is grotesquely and unavoidably expensive. Justifiable only when the value of the action is grotesquely high or when the evidence obtained in England can be used to settle the case in “ROW”. (HaHa). But the identity of the expert witnesses has to be carefully observed by the judges in England, lest England end up with the absurdities of patent litigation in the USA.

Dear Max Drei,

It is clear that a cross-examination system like in the UK can bring a much better acceptable result, but as you say, at what cost? Even when the UK was still in the UPC system, this type of cross examination was never envisaged. The costs at the UPC are horrendous enough, not to become even higher with a cross examination system. I fear that in view of the costs involved, UK courts might not be able to sustain their position in litigation. The UPC might take over, especially whith its long arm reach.

That two thirds of the decisions of OD are set aside by boards is a real problem, which cannot be brushed away as the EPO would like to do. For the EPO a decision of an OD which is not appealed is counted as a confirmation of said decision. There are lots of reasons not to appeal, one important one being that the parties settle. This does not necessarily mean that the decision would have been upheld in appeal.

The case which arrive in court are not even the top of an iceberg. There are much more litigations which will not end in court, be it for the cost involved.

By the way, I have read recently the that Ortovox and Mammut have settled their dispute on finding devices for people victim of avalanches. It is interesting in that the court of first instance of the UPC considered claim 1 as granted valid and infringed, but the Swiss federal patent court considered claim 1 as granted invalid, and this with the same prior art. To me the decision of the Swiss federal patent court was the right one. The UPC judges had manifestly not understood the claim in spite of all the trara of interpretation. I also wonder how such a claim ever passed examination. .