EP 2 137 782 B1 relates to a device (claim 1) and a method (claim 11) for converting light energy into electrical energy and/or hydrogen by using a living plant for converting light energy into a feedstock for a microbial fuel cell.

The infringing device

Brief outline of the case

The patent was granted by the EPO and no opposition was filed.

The proprietor filed for infringement at the LD The Hague CFI UPC.

The alleged infringer, Bioo, sold in The Netherlands a device which, according to the proprietor, infringed directly and indirectly, claim 11 of the patent.

Bioo filed a counterclaim for revocation of the patent, arguing that the patent was invalid for a series of reasons.

The LD-CFI decided that none of the objections against the validity of the patent were persuasive.

The LD-CFI held the patent infringed by equivalence and ordered to cease and desist with immediate effect from infringing directly and/or indirectly EP 2 137 782 B1.

The LD-CFI also ordered a specific wording for a letter to be sent to customers or to be published on the website of the infringer based on Art. 64 UPCA and Union law.

What is the patent about?

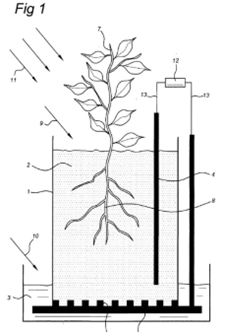

The teaching of the patent is to create a Microbial Fuel Cell (MPC) that is independent of externally furnished fuel. This is achieved by introducing a living plant into the system as a constant supplier of organic material to the reactor, thus creating a Plant-based-Microbial Fuel Cell (“P-MFC”).

The organic material, produced by the plant through photosynthesis, is used as feedstock to the fuel cell for the anodophilic micro-organisms in the reactor.

Interpretation of the claim

The LD-CFI referred to the Order of the CoA of 11.03.2024 in case CoA 335/2023, Nanostring/10 x Genomics, page 24.

The CoA also clarified

(i) that the principles for interpreting a patent claim apply equally to the assessment of the infringement and to the validity of a European patent and

(ii) that a patent must be interpreted from the point of view of the average person skilled in the art.

The LD-CFI added that prosecution file is generally not part of common general knowledge of the skilled person.

Skilled person

The LD-CFI defined the skilled person as to be an individual (or a team) with a scientific background (PhD) in biochemistry, electrochemistry, and possibly microbiology or environmental engineering and about 3 to 4 years of working experience in the technical field of microbial fuel cells.

The teaching from the description

The description teaches the skilled person that a ”feedstock” may, optionally, contain electron donor compounds, and preferably does.

The living plant is part of the process as generator/supplier of electron donor compounds. That the plant is part of the “reactor” follows from claim 11, because the anode compartment is taught to comprise a living plant and the anode compartment is in turn part of the reactor.

The feature “compartment”, means according the LD-CFI, that the anode and cathode should be positioned such that they are functionally separate to avoid short-circuiting. The skilled person knows the purpose of separation and understands that this can be achieved either by a membrane or by other means, such as e.g. soil, as found in the description.

Infringement

The LD-CFI held that the scope of protection in the case of infringement is assessed in two steps, applying Art. 69 EPC and the Protocol.

The first step evaluates ‘literal’ infringement of the features of the patent in view of the claim construction is evaluated. In a second step, if the patent is not judged to have been literally infringed, equivalence is assessed.

The LD-CFI held that the Bioo Panel literally applies all features of the claim except for the location of the plant and its roots, together with the micro-organisms, in the anode department. In the Bioo Panel the roots of the plant are in an upper compartment, whereas the anode, with the microorganism, and thus the anode compartment, is located at the bottom of the lower compartment.

To decide on infringement of claim 11 by equivalence, it needed to be established whether the setup of the Bioo Panel, with its two compartments, is equivalent to the method claimed which requires the plant and its roots to be in the anode compartment, with the microorganism.

The LD-CFI referred to Art 2 of the Protocol.

The test applied to the assessment of infringement by equivalence is based on the case law in various national jurisdictions.

The LD-CFI came to the conclusion that a variation is equivalent to an element specified in the claim if the following four questions are answered in the affirmative:

1) Technical equivalence: does the variation solve, essentially, the same problem that the patented invention solves and perform, essentially, the same function in this context?

2) Fair protection for patentee: Is extending the protection of the claim to the equivalent proportionate to a fair protection for the patentee?

3) Reasonable legal certainty for third parties: does the skilled person understand from the patent that the scope of the invention is broader than what is claimed literally?

4) Is the allegedly infringing product novel and inventive over the prior art?

Technical equivalence

The LD-CFI was convinced that organic material can travel from the upper compartment of the Bioo Panel into the lower compartment, where it reaches the anode and where the anodophilic microorganisms are present.

The set up of the Bioo Panel is thus considered technically equivalent to the teaching of the patent as the plant is part of the reactor and is a source of additional organic material for the battery. The plant in the Bioo Panel has the same function as in the claim and solves the same problem and does this in a similar way.

Fair protection for the patentee

The patent claims a new category of microbial fuel cells, by introducing a plant into the device/reactor and to obtain electricity from organic material originating from the photosynthesis by that plant and thus from light energy.

A fairly broad scope of protection is therefore in line with the contribution to the art.

Reasonable legal certainty

The requirement of legal certainty is met if the skilled person understands that the patent claim leaves room for equivalents.

The teaching of the patent is to add a plant to a an MFC to provide additional feedstock to make the MFC independent of externally provided feedstock. The skilled person will understand that the variation of the Bioo Panel is another way to obtain this result in a similar way.

Bioo Panel novel and inventive?

At the priority date, the Bioo Panel would have been novel and inventive over the prior art because of the introduction of a plant as part of the device as a supplier of additional fuel for the battery/reactor.

Comments

It is interesting to note that the infringement related to the method claim of EP 2 137 782 B1 and not to the device claim.

Definition of the skilled person

For the LD-CFI the skilled person has a PhD level of knowledge. This is in clear contrast with T 1832/14 according to which a doctoral thesis is not representative of common general knowledge.

Same criterion of interpretation for validity and infringement

Unless G 1/24 is issued, this view might be theoretically possible, but is presently not applicable at the EPO for lack of competence in infringement by the EPO.

If the EPO where to adopt this stance, it would mean that claiming non-disclosed equivalents would have to be accepted. The direct consequence is that non-disclosed equivalents could not represent any more added matter should they be claimed.

Conditions for infringement by equivalence

It will have to be seen whether the CoA upholds the four criteria set up by the LD-CFI.

Criteria 1, technical equivalence, seems the one that matters, and the other three criteria are variation around the same theme. Whether they are necessary remains to be seen.

Criteria 4 seems, at a glance, a kind of inversed “Gilette defence”.

Relations between proprietor and infringer

Bioo was a licensee of the proprietor, but ended the license agreement as it found that the method claimed 11 of the patent did not work.

Bioo came up with a different, allegedly improved, design with two compartments, see EP 20382828 = EP 3 972 021 A1. This application is deemed withdrawn for non-payment of the examination and renewal fee.

Claiming the priority of EP 20382828, a new application was filed under the PCT, published as WO/2022/058500 A1 = EP 4 214 785 A1. This application should proceed to grant.

WO 500’ was mentioned a few times in the decision, but also EP 20382828

UPC_CFI_239/2023 App_549536/2023 CC_588768/2023

Comments

41 replies on “UPC LD The Hague – Infringement by equivalence of EP 2 137 782 B1”

So, if I see it right, the emerging jurisprudence of the UPC tells us that i) the scope of protection given by a claim is one thing, whereas the “meaning” of that claim is quite another, ii) that meaning is the same, whether for literal infringement or for novelty iii) the EPO Gold Standard lives iv) but NOT the mantra that if what infringes comes instead before, then by definition it prejudices novelty, that mantra being now dead and buried v) national law doctrines that are a “squeeze” between validity and infringement, variously dubbed “Formstein” or “Gillette”, are being adopted by the UPC?

Long ago, the UK Supreme Court explained that to divine the meaning of a claim one must ask oneself “What was the patentee using the language of the claim to mean (to the skilled rechnical reader”. Is not the UPC now on the same track?

What’s not to like, in all of this?

Max, I must congratulate you on summarising very concisely points that I have struggled to convey in comments on a different post. With regard to the “meaning” of the claim, I would instead term that the “normal” claim scope. I agree that this should be determined by reference to both cgk and the description / drawings – though good luck persuading Mr Thomas on this point!

@ Doubting Thomas,

I need not be persuaded of anything and you can save this type of useless comment.

If the applicant proprietor wants the claim to have a meaning which is more restricted (or even broader) than what he is saying in the claim, then he should put it in the claim and not try to conceal something, with the aim of escaping prior art during examination or to get out more should an infringement arise.

You might not like it, but in plain English, I call this a deliberate attempt of cheating,.

An independent claim is always an the result of the generalisation of one or more specific embodiments. The role of the EPO is not to try to divine what the applicant/proprietor had in mind when he drafted its claim. With proper support in the description, there is no need for the EPO to divine anything.

The two comments coming after mine, and the somewhat heated difference of opinion, have set me thinking about a possible difference between the philosophy of civil law in England and that on the European mainland.

The notional reader of a patent is a person of skill and knowledge in the relevant technical field. What the claim means is what it means to such a skilled person. Can we all agree on that?

However much technical background a patent judge in England possesses, they would not have the temerity to declare themself that person skilled in the art. Instead, in disputed proceedings, in the case of disagreement between the parties what the claim means, the opposing parties bring forward respective argument and evidence, to enable the judge (under the law deemed to be NOT the notional reader of the patent) to “don the mantle” of the skilled person and, wearing that clothing, go on to construe the claim (as a question of law, not fact) basing themself exclusively on that evidence brought before the court.

Is it perhaps otherwise at the EPO? I mean, does an EPO tribunal consider itself to be a person skilled in the art, whereupon the bringing forward of evidence of what the skilled person thinks is impertinent, an affront to the tribunal, and anyway superfluous, the declaration of the tribunal itself, as to what the claim means, based exclusively on their own acquired level of technical knowledge and expertise, being decisive and final?

Hugh Laddie reminded us all that in England, the courts of civil law are not “a branch of social services”. He was contrasting the English adversarial system with the system in Germany, where it sometimes seems to me that the courts see their role as that of a kindly parent or uncle mediating between squabbling children, then “laying down the law” (my word is final) to end the dispute between the warring parties. How do the EPO Boards of Appeal see their role?

Is that difference an explanation for the difference of opinion between DXT and DT? If not, what is the explanation?

Der Max Drei,

I fully agree with you that the notional reader of a patent is a person of skill and knowledge in the relevant technical field. What the claim means is what it means to such a skilled person.

There is certainly a cultural divide in the way legal matters are apprehended on different sides of The Channel.

The British system is that of common law, whereas on the continent the legal system goes back to Roman law.

When it comes to infringement, the judge on the continent will not necessarily resort to an expert, whereas this appears to be the case in the UK. There is no cross examination of experts as in the UK. There is also no cross examination of witnesses. If two opposite expert statements are filed by the opposing parties, the judge will decide what is more likely to be correct or not, without hearing and certainly not cross examining the experts.

It is otherwise at the EPO. I do not remember one case where in opposition and appeal an expert was heard. Some parties request it, more in appeal. Such a request is always turned down as the board normally says that it is able to assess the peculiarities of the case, without calling an expert. There have been a few cases in which a party has brought forward an expert statement, but the expert will not be heard. When a former member of the boards acts as expert for a party this is indeed not well received and will in general be ignored. I have also seen negative comments on such statements of former colleagues, even if they have left the EPO a while ago (For three years after departure, they are anyway barred from appearing before a board, even it it is a different board than the one the were working in).

I am of the opinion that an EPO deciding body considers itself to be a person skilled in the art. The bringing forward of evidence of what the skilled person thinks is neither impertinent, nor an affront , but in essence superfluous. The declaration of the of the deciding body itself, as to what the claim means, is based exclusively on their own acquired level of technical knowledge and expertise, being decisive and final.

When cases ends up before a civil law court on the continent, there will always be a plaintiff and a defendant, but the system is not adversarial as in the UK. This also explains why it is cheaper to go before a court on the continent.

Judges might also try to bring the parties to settle, as this would save them writing a decision. I knew a judge at the Oberlandesgericht Dresden acting in IP matters . His name was Kaiser, but its nickname was Vergleichskaiser (Settlement emperor).

I think that the above considerations explain a lot of the differences between Doubting Thomas and myself.

Max, I can agree that what a claim means is what it means to a person skilled in the relevant art. To that, I would add the caveat that the skilled person would determine meaning by considering all relevant context, namely:

(a) common general knowledge;

(b) the wording / construction of the claim set; and

(c) the disclosures of description and drawings (of the application as filed).

It seems to me that the main difference between my views and those of Mr Thomas are that he would omit bullet point (c), at least in those cases where the meaning of the claims is clear from (a) and (b) alone.

Courts of the EPC Member States invariably use all of (a) to (c) when interpreting claims, whether for assessing infringement or validity. Thus, whether or not the judges of those courts choose to don the mantle of the skilled person (as opposed to considering evidence from the parties on technical matters, including matters of claim interpretation), their approach will still diverge from the EPO’s with respect to bullet point (c) above. To me, THAT seems to be the fundamental philosophical difference on this topic.

@ Doubting Thomas,

Courts of the EPC Member States invariably use all of (a) to (c) when interpreting claims, whether for assessing infringement or validity.

The EPO also uses all of (a) to (c) when interpreting claims, for assessing validity.

Whether you like it or not, the EPO simply ignores what is disclosed in the description, when the applicant/proprietor gives a feature in the claim a different meaning in the description than that the skilled person derives from the meaning it can be given when reading the claim. I refer to T 1127/16, mentioned in one of my replies to a comment of yours:

“… the description cannot be used to give a different meaning to a claim feature which in itself imparts a clear, credible technical teaching to the skilled reader. This also applies if the feature has not been initially disclosed in the form appearing in the claim. Otherwise third parties could not rely on what a claim actually states (cf. Article 69(1) EPC: The terms of the claims determine the extent of protection whereas the description is only used to interpret the claims) and Article 123(2) EPC would become meaningless in respect of amendments to the claims”.

I have nothing to add, but that, for the reason above, the assessment by the EPO in validity might be divergent with that of a national court or the UPC. Art 69 and the Protocol do merely define the scope of protection. It is not the task of the EPO (besides when it comes to Art 123(3) in opposition) to define the scope of protection.

This is inevitable in view of the cut-off point between the grant of the patent and its use afterwards, when it comes to infringement.

You might call this the sin from birth of the EPC. Any gripes about this, is thus to be adressed to the fathers of the EPC.

When the English judges decree that the claim must be taken to mean what it says, and that those construing the claim must accept that the drafter of the claim knew what they were doing when they wrote the claim and so every word in it has to taken as being there deliberately, for a purpose, even if that purpose is not apparent to the construer, then are they not on the same line of thinking as the EPO with its “primacy of the claim” philosophy?

Reading DXT I get the feeling that the result of claim construction is binary. Either the meaning of a claim is clear in and of itself, or it has a meaning that is contradicted by the description. My feeling is that “life isn’t like that”. In most patents, the claim, considered in isolation, stripped of the context bestowed on it by the description and drawings, is less than 100% unambiguous in meaning. In most cases, the description of the invention in the description complements the definition of the invention in the claim and so is helpful for the task of ascertaining what exactly is the meaning of the claim. Construing the claim in the context of the description clarifies the true meaning of the claim.

Third parties, and Examiners in the EPO, just as the judges in England, can then all rely totally on what the claim says, as the true “meaning” of the claim. Thus, in pemetrexed, the claim said “sodium” and that’s what the claim meant to the English judge, despite their manifest displeasure with that outcome.

Meanwhile, the “scope of protection” given by the issued claim is not the same thing and determining it is an exercise different from ascertaining what is the meaning of the claim.

Dear Max Drei,

We have discussed the topic a few times, but I never claimed that the result of claim construction is binary. I agree with you that there is no absolute clarity, it all depends on what one is looking for.

Simple examples can sometimes lead to over simple conclusions, like a claim is either clear or not. They should simply help to get the gist of what is meant. No less, but no more.

Balance of probabilities is the key here: is it more probable than not that the claim has a proper technical meaning as it aligns a succession of technical features. What I cannot agree to, is trying to give a feature in a claim a different meaning in the description, from that a skilled person would understand when reading the claim.

Construing the claim in the context of the description indeed clarifies the true meaning of the claim. I would however add a big proviso: this is only valid if there is no discrepancy between what the claim suggests to the skilled reader and what the meaning for the skilled person would be when reading the description. This should not be too difficult to understand and to accept.

France lived happily for over a hundred years with a patent law not requiring claims. The legislator did however once decide that this was confusing and introduced claims. When claims are drafted, they should help to understand the boundaries of what is protected, but it should not normally be necessary to refer to the description to realise what is the true meaning of the claim. At this rate, it would be better to get rid of the claims, but then we are back to square one….

Max, I venture a further possibility, which is “high decoupling” vs “low decoupling” styles of thought and argument.

In brief, “high decouplers” are those who are able to break down problems or statements into discrete integers of argument and logic, hypothesise situations or counterfactuals arising from those discrete units, follow them to their logical conclusions and then re-synthesise the insights from each of those steps into a holistic answer (or perhaps more than one answer).

“Low decouplers” instead view a problem or a statement as a whole, inseparably from (their perception of) its context, and do not perform the same mental exercise of taking it apart to put it back together.

When high decouplers debate low decouplers, the result can be one of mutual incomprehension, even talking past one another or antagonism, as both sides feel the other is missing their point. High decouplers perceive low decouplers as incapable of focusing on the core logical issues, or worse, as trying in bad faith to derail the discussion onto irrelevant and poorly-defined tangents. Low decouplers meanwhile view high decouplers’ relentless logic as missing the bigger picture and ignoring real world context.

This is explained quite well here: https://unherd.com/2020/02/eugenics-is-possible-is-not-the-same-as-eugenics-is-good/

Most of us are neither purely high nor purely low decouplers. However, having seen the different argumentation styles on display on the fraught issue of claim interpretation, my feeling is that DXT (like many examiners) falls more toward the “low decoupler” end of the spectrum, and DT (like many representatives) more toward the “high decoupler” end. For the former, it is unthinkable to break down the issue into logical units rather than considering the fact that the EPO has always done things a certain way or that the Boards have predominantly ruled such-and-such. For the latter, this feels like a determination to avoid considering the fundamental legal principles at play and following them to their logical endpoints even if that might point to the EPO or its Boards being wrong.

I wonder if this might explain why this issue is so intractable?

If so, it is more than a little ironic that the “high decoupling” argument, approaching the issue as a strict logical thought experiment, devoid of the context of established EPO practice, leads to a place whereby the context provided by the description is always important; while the “low decoupling” argument, with its focus on the context of established EPO practice, leads to a place whereby the description is to be disregarded, regardless of the context it provides for the claims.

Mouse, thank you for your very astute comments. There may well be something to them. Your observation regarding the irony of the situation also gave me a wry smile.

Not having been acquainted with the writings of John Nerst, I had never before considered myself as a “high decoupler”. However, now I know what that means, I am perfectly happy to identify as such.

I think that you have hit the nail on the head with regard to how I perceive DXT’s arguments, namely as “a determination to avoid considering the fundamental legal principles at play and following them to their logical endpoints even if that might point to the EPO or its Boards being wrong”. Indeed, as someone who has analysed the situation from first principles, having case law quoted at me (even very firmly established case law) stands precisely zero chance of swaying my views unless it is accompanied by an explanation of how the conclusions in that case law can be derived from the EPC and/or general principles of international law.

There are perhaps other factors which lead to the debate becoming intractable.

Firstly, as an ex-examiner, DXT may well be inclined towards agreeing with interpretations of the law which allow for quick and decisive determinations on whether an application (or patent) meets the requirements of the EPC. Such interpretations facilitate quick (and arguably “efficient”) examination, as they aim to eliminate as many “grey zones” as possible, thus making matters seem much more black and white.

I can understand why, in general, examiners at the EPO might favour such interpretations of the law. Indeed, given the time pressure under which they operate, it is perhaps only natural that such interpretations would become very appealing.

In this respect, there may be an element of perception bias (or wilful blindness). That is, if an interpretation of the law has proven to be very useful, and to deliver results that are “good” (from the EPO examiner perspective), I could understand why that might make an (ex-)examiner inclined to become staunch, vociferous and dogmatic in their defence of that interpretation, and even to deliberately misrepresent opposing viewpoints in order to make them appear easier to discredit / disprove.

Secondly, I am more inclined to accept only those interpretations of the EPC which are clearly derivable from the EPC (as interpreted according to the principles of the VCLT) and/or from general principles of international law. As on this occasion, this can lead me to settle upon interpretations which do not align with current mainstream thinking at the EPO.

As I will have thought long and hard before settling upon what I believe is the correct interpretation, it can be somewhat of a let-down when those arguing against that interpretation do not appear to appreciate the potential relevance of the factors that I found to be most persuasive. This is not because I am 100% confident in the persuasive power of those factors. Quite the opposite. It is because I am keen to “pressure-test” those factors, to establish whether my conclusions are indeed legally robust. Thus, DXT’s avoidance of engagement with the fundamental legal principles not only leads to the debate becoming intractable, it steers it away from the points where – at least for me – input from others could help to move things forward.

@ Anon Y. mouse

I read your comments about High/Low decouplers with interest, as well as the reference to it, but with a certain amount of irritation.

When you consider DT and representatives as rather high decouplers and examiners, like myself in my previous job, as low decouplers, you are trying to create an antagonism between examiners and representatives. This is not correct. Would you, for instance, consider judges as well low decouplers?

I have always considered that examiners and representatives are sitting in the same boat: giving overall a service to inventors. This does however mean that they each represent distinct interests. On the one side, you have representatives who want to get the maximum out for their clients, and on the other side examiners are there to defend, what I would say the public domain and only grant or maintain patents which are worth the monopoly they confer.

It is thus quite normal to have divergent views. I made it clear at numerous occasions, that I fully understand what DT wants, but I cannot agree with it in substance. This has nothing to do with whether “boards have predominantly ruled such-and-such”. What the boards say is just vindicating my position, but no more.

When in the example of the ventilator and/or the perforated layer, DT comes with a clarity objection, I do actually wonder who is actually the low decoupler.

My experience is that in opposition, the proprietor often wants to deny on the basis of the description what the opponent queries in the claims. It happens however, that once the former proprietor is becoming opponent, the tables are turned and what was valid one day is not valid on another day.

I would therefore go as far as to say that in when he is acting for the proprietor, the representative behaves like a high decoupler and when he is acting as opponent, he is behaving like a low decoupler. At the end of the day the deciding body will have to take a decision, and it is clear that one of the two parties will not be pleased.

Neither the BA nor the examiners have devised the EPC, they are there to interpret and apply it to the best of their knowledge and competence. It is not the boards or the examiners who invented the primacy of the claims, but the EPC, as a result of the historical divide between grant and infringement. That this is not the way that some people like DT, and probably yourself, conceive it, but this is reality. A holistic approach of an application might be ideal, but we are not here to long for an ideal, we have to deal with reality.

By trying to create a distinction between what you consider high and low couplers, you are simply crating an unnecessary, and in my eyes dangerous, antagonism between representatives and examiners and/or the boards.

Mr Thomas, it is revealing that you see representatives and examiners as essentially playing for opposing teams. That might help to explain why you continually conflate my motivations with the interests of a certain (avaricious) type of patentee. It does not appear to have occurred to you that my motivation might be something quite different, such as a properly functioning (including logically consistent) and well-balanced patent system.

I also had to smile when I saw your response to Mouse’s comments, as it demonstrated not only the levels of irritation that have become all too familiar to me but also included your trademark move of casting aspersions on the motivations of those whose views do not completely align with yours.

Whilst you claim to completely understand my views, I remain unconvinced. Your comments simply do not demonstrate to me that you have understood why I have reached the conclusion that the principle of the primacy of the claims is not consistent with the uniform concept of disclosure. Instead, your comments have done more to convince me that you main aim is to simply repeat your opinions as loudly and as often as possible until everyone else is browbeaten into submission.

However, as that might not be entirely fair to you, I will offer you one more opportunity to demonstrate that you really do understand my viewpoint. Brace yourself: this will involve considering yet another hypothetical scenario, which is as follows.

– Two EP applications, EP1 and EP2, are filed by the same applicant.

– EP2 is filed less than 1 year after EP1 and claims priority from that earlier application.

– Both EP1 and EP2 are filed WITH claims.

– The description of EP2 is IDENTICAL to that of EP1.

– The as-filed claims of EP2 are IDENTICAL to the as-filed claim of EP1.

Based upon this scenario, I would ask the following questions.

1) Is it certain that the EPO will find the ORIGINAL claims of EP2 to be entitled to priority from EP1? If not, what could cause the EPO to find a lack of entitlement to priority?

2) Is it possible that the EPO might find the ORIGINAL claims of EP2 to be novel over the disclosures of EP1? If so, how could that happen?

3) Is it possible that the EPO might:

– rule that the claims of EP2 are NOT entitled to priority from EP1; but

– effectively contradict that ruling by determining that the IDENTICAL claims of EP1 meet the requirements of the EPC?

If so, how could that happen?

I would also welcome answers on these points from any other commentators.

DT, sorry but I’m not seeing the point of your hypo. Out of a plethora of possibilities, I take the extreme ends.

First, the claim is perfectly in tune with the disclosure. Both the “same invention” directly, unambiguously and enablingly disclosed, across the scope of the claim.

Second, the claim is grotesquely inconsistent with the disclosure, indubitably the invention defined by the claim different from the invention disclosed in the description and drawings.

For the first scenario, the answers to your questions must be: Y/N/N.

For the second scenario: Same answers.

Where am I missing your point? Am curious to read answers from other readers.

When I am acting for an opponent I reach for such arguments as might succeed and I find the counter arguments put forward by the patentee unconvincing. Quite the opposite when I am acting for the patentee But I have stopped all that now I am retired. These days I just want to nurture the EPO reputation for high quality patentability jurisprudence. I do not see myself as being in one camp or the other. I like the way the thread is developing.

Max, where the claims are “perfectly in tune” with the description, I would agree that the answers to my questions are: Y/N/N.

I am not sure precisely what you mean when you refer to “the invention defined by the claim different from the invention disclosed in the description and drawings”. However, I am happy to provide a pointer towards where my thought process has led me.

What would happen if the EPO were, for the purposes of interpretation, to STRICTLY apply the “primacy of the claims” approach to the application which is the subject of examination proceedings BUT a different (ie “whole document”) approach to all other (priority, prior art, etc) documents in those proceedings?

If that were to happen, can you envisage a scenario in which the answers to my questions might be: N/Y/Y?

@ Doubting Thomas (and Anon Y. mouse)

It is nice to see how two people, you and Anon Y. mouse, are full of themselves and think they are the bees knees and know it better.

I never said anything about it, but I have studied law, a long time ago, and I consider that I am as aware as yourself of fundamental legal principles and of the VCLT. I had also the opportunity to witness the evolution from the drafts of a “Community Patent” to the EPC.

I do not avoid engagement against differing views. I simply refuse to jump over every stick which is put in front of me. Who do you think you are when you allow yourself to put questions to me “to be sure that I have understood your point”? Are you a professor of law wanting to see if its students are agreeing with its point of view? Max Drei replied, I will not.

I will not reply to somebody thinking that he, and only he and his likes, have the truth. Have you ever heard of La Fontaine’s fable of the frog that wanted to be bigger than the ox. A bit more modesty would suit you well. Like when it came to the adaptation of the description you claimed that the boards were wrong, until one legal member in T 56/21 went along your way. One swallow does not make a spring (literal translation of a French proverb).

You have developed a nice theory “The uniform concept of disclosure”, but it remains a theory and not everybody might agree with it. I have given you reasons why I do not agree with it, but you still want to convince me that I am wrong. Attrition will not make me move.

I have learned during my law studies, and my active time at the EPO, that when it comes to legal matters, different points of view emerge depending on which side you stand. This is quite normal and the reasons why we need judges/arbitrators to take decisions when two parties argue.

What I have noticed in my long career, is the different points of view when a party is opponent or is proprietor.

At the end of the day, the EPO has to take a decision and one of the two parties will be dissatisfied. This is exactly the point Max Drei made in his last comment. I have never seen representatives and examiners as essentially playing for opposing teams, and certainly not in opposition. They have a different role and this the reality. Call it antagonism, if it helps you ego, but stop thinking that you and only you are right.

My blog is not there to be a tribune for some people with a massive ego and thinks he only knows what is best. From now on, I will promote to trash or delete part of your comments when I find those irritating or insisting unnecessarily of some points of disagreement. Enough is enough. With your last comments you went too far. Take it as you want, but you have been warned. Your are only victim of your absolutism.

Can I envisage, you ask me, DT. Answer No. Sorry. Your imagined EPO behaviour is beyond my imagination. Do you perhaps have a specific TBA Decision which illustrates the unease you are feeling?

Max, I do not have any case law in mind. Just my analysis / logical deductions.

Whilst I will freely admit that there is perhaps a chance that I am missing something important, my analysis and deductions lead me to conclude that absurd situations can arise when there is STRICT application by the EPO of:

– a “primacy of the claims” interpretation approach for the claims of an application undergoing examination; BUT

– an interpretation based upon the “uniform concept of disclosure” for ALL other (parts of) documents in the examination proceedings.

The “uniform concept of disclosure” is an approach which aims to determine the subject matter that can be clearly and unambiguously derived from the disclosures of a document AS A WHOLE. This makes it very different to the “primacy of the claims” approach, especially where the description of a patent document includes a “custom” definition of a term used in the claims.

In that scenario, the “uniform concept of disclosure” interpretation of the term in question will be different to the (“standard”) interpretation under the “primacy of the claims” approach. It appears to me that logical consequences of this observation are as follows.

1) Examination of claims of EP1 or EP2:

“primacy of the claims” applied => claims interpreted using the STANDARD definition of the term.

2) Assessment of entitlement to priority of EP2 from EP1:

“uniform concept of disclosure” applied => the WHOLE DISCLOSURE of EP1 is interpreted using the CUSTOM definition of the term.

In this scenario, and based on the different interpretations of EP1 mentioned at 1) and 2) above, it seems to me that the answers to my questions will be: N/Y/Y.

Of course, if the “primacy of the claims” approach were to be applied also when interpreting a prior art (or priority) document, then the answers might be different. However, it seems to me to do that would be inconsistent with the requirement for subject matter to be UNAMBIGUOUSLY derivable from the disclosures of a document. That is, if it is clear from the description of EP1 that the applicant intended to define their invention in accordance with the “custom” definition, and ONLY the “custom” definition, it would defy all logic to assert that the ”standard” definition is UNAMBIGUOUSLY derivable from the disclosures of EP1.

Max, I would also ask you to consider whether, in the hypothetical scenario that I have set out, the EPO might:

– grant a patent based upon EP1, with claims that EXCLUDE the “custom” definition of a term; AND

– grant (to the SAME APPLICANT) a patent based upon EP2, with claims that INCLUDE the “custom” definition of that term.

That is, assuming that the inclusion / exclusion of the “custom” definition makes a difference to the EPO’s interpretation of the subject matter of the claim, is it fair to conclude that the EPO would NOT perceive there to be any issue of double patenting?

According to G 4/19, the issue of double patenting can only arise when a claim of a patent (or patent application) which is the subject of proceedings before the EPO relates to the “same subject matter” as a claim of a patent granted to the same applicant. But how does the EPO determine the subject matter of the claims of the two cases in question? That is, which interpretation approach does the EPO use to determine the subject matter of the claim of the granted patent (that is NOT the subject of the proceedings)? Is it the uniform concept of disclosure or instead the principle of the primacy of the claims?

Of course, national courts would not have any difficulty in determining that the above-mentioned claims of EP1 and EP2 in fact relate to the “same subject matter”. But would the EPO see things differently?

@ Doubting Thomas,

I will now come with a concrete example to illustrate, once more, my point of view.

In T 335/22, published today, there was a discussion about the interpretation of the terms “solder balls” between proprietor and opponent. The proprietor considered that the feature was clear, which, in my opinion, is a priori correct, and the opponent was of the opinion that after soldering there were no solder balls left. In my opinion both were right.

In such a case it was legitimate to look at the description, [0042], and to come to the conclusion that the solder balls only exist before bonding. It is part of common general knowledge of an electronic engineer that solder balls can be used for bonding, but that those solder balls disappear when bonding has taken place. It was interesting to note that the description indirectly confirmed this view, but this was not a necessity as such.

It turned out that the description indeed conferred an interpretation of the claim which was coherent with the claim as such and did not try to say “in the present case solder balls are defined as follows…..”

What you wish is something different, you bring in a claim a feature having a given meaning to the skilled person, but in the description, you want to give it a different interpretation. It might be important for the scope of protection to have a different definition in the description, but validity and scope of protection are two different things, cf. G 2/12, Reasons VIII.2. 6.(b).

Primacy of the claim is not an absolute criteria as you try to make out. It simply has to be used in a reflected manner, but the reader of the claim should not be forced to systematically look at the description in order to interpret the claim.

The above considerations about “solder balls” are perfectly in line with what I said when giving the example of the ventilator and the perforated layer.

All of this discussion is very interesting, but I wonder if we are losing sight of the fundamentals here.

Either the description influences the intereptation of the claims, or it does not.

If the description influences the interpretation of the claims, then the EPO is ultra vires in asking for it to be amended, because that interpretation only has a role in proceedings before national courts or the UPC, which are not the EPO’s responsibility.

If the description does not influence the interpretation of the claims, then it is irrelevant whether it is adapted or not.

When it comes to equivalents, these are variations falling *outside* the “literal” claim interpretation (even when taking into account the description). They are embodiments which would not fall within a “normal” claim interpretation even based on the description. So, again, the content of the description – amended or unamended – is irrelevant.

What am I missing here?

What are you missing, FRANDalorian?

Perhaps the EPO’s duty to examine for compliance with Art 84, EPC (which ascribes tasks not only to the claim but also to the description of the invention defined by that claim).

Does there ever come a point when the content of a description is prejudicial to the clarity of the definition of an invention given by a claim that is presented at the end of that description?

Is there a point at which a description fails in its duty to support that definition?

Reasonable minds differ. A lot of people would like a clear answer to these questions. What are yours?

@ FRANDalorian

I allow myself to say that you are missing a lot.

Besides what Max Drei told you, i.e. Art 84, support by the description, there is another point not to forget.

The general idea is that you cannot have statements in the description which are at odds with the subject-matter of the claims. Depending on the case, either the (independent) claim or the description will have to be adapted.

I come back to my example of the ventilator. If the description speaks about a ventilator defined as blowing hot air and the claim only refers to a ventilator, this claims offends Art 123(2) as you claim something broader for the skilled person than the ventilator “customised” in the description. The claim is not supported by the description, which is a wording also used in decisions of the boards when it comes to Art 123(2).

In such a situation the EPO would never request amending the description to delete the customisation of the ventilator as this would be a clear cut breach of Art 123(2) not only for the claim, but also for the description. In this situation, it is the claim which has to be amended in order to bring it in alignment with the description.

The situation is different when a feature F is disclosed in the description as being optional, is, during examination or opposition, added to an independent claim in order to overcome an objection of lack of N or IS. As soon as feature F is added to the independent claim, then feature F cannot be any longer considered optional in the description and the EPO will request the description to be amended so that description and claim are aligned to each other.

The whole problem raised with DT is that he wants to “customise” in the description features which can have a different, in general broader, meaning in the claims, e.g. the ventilator is blowing hot air in the description vs. a ventilator which is merely blowing air in the claim.

Customising in the description features from the independent claim is a prime source of problems, see the ventilator example.

Primacy of the claims means that claims have to define the matter for which protection is sought, without having to resort to the description to determine exactly what each feature of the claim actually entails, and without having to determine the scope of protection afforded by the description. Art 84 is there to assure that claims are clear by themselves, and properly supported by the description. Art 123(2) is there so that the applicant/proprietor cannot claim things he never envisaged when filing the application.

It is furthermore not the task of the EPO to determine whether, not claimed “equivalents”, would fall under the scope of protection of the claims. This is for a court dealing with infringement.

@Doubting Thomas

The « uniform concept of disclosure » to which you refer actually relates to the interpretation of prior art (CLB I.C.4.1). Section II.D.3.1.2 you had mentioned relates to the validity of priority claims.

The relevant section of the CLB regarding claim interpretation is II.A.6.1. It clearly sets out the rule of the broadest technically sensible meaning for claim interpretation during examination.

A significant number of recent BOA decisions apply this principle : T 1705/17, April 2021 ; T 1208/21, April 2024 ; T 1628/21, February 2024, T 2764/19, June 2021 ; T 2502/19, December 2022 ; T 1654/19, February 2023 ; T 1553/19, October 2022 ; T 1266/19, July 2023 ; T 2007/19, October 2022 ; T 1382/19, July 2023.

The referral decision T 439/22 of G 1/24 cites T 1628/21 (reason 6.2.1) and the rule of interpretation set out in CLB II.A.6.1, although not in very explicit terms and without citing the CLB.

The logic of your position of extensive reliance on the description for claim interpretation might lead to a very strict scrutiny of the support condition of Art 84 during examination, to ensure that this condition is met across the entire breadth of the scope of claims. The ED might look at the disclosure of embodiments or examples and impose severe restrictive amendments when it finds the language of a term is too broad. This would be in sharp contrast with the generally liberal practice of the EPO in this respect. Needless to say, this would be most unpopular to practitioners but also to examiners, because of the increase of their workload.

Mr Hagel,

I cannot but agree with your conclusion.

As I explained in my reply to FRANDalorian wanting to “customise” the definitions of claimed features in the description, is simply not tenable. It defies the mere raison d’être of the claims, if for each claimed feature, the reader is obliged to check in the description what could be the real meaning and interpretation to be given to said feature of the claim, and hence to have a prime idea of the scope of protection.

Such a way of drafting claims would result in numerous objections under Art 84 and/or Art 123(2), with as you point out, entails a lot of work for the EPO and render a FTO opinion very complicated.

I consider “customising” claimed features in the description, nothing more that an unfair attempt to conceal what the invention actually is about. For all this reasons, the EPO is right of not accepting such a behaviour from the applicant/proprietor.

A spade has to be called a spade, and if a court dealing with infringement considers that the spade can have some variations, there is nothing to say about it. It is not the job of the EPO to try finding out what variations the spade could undergo when looking at Art 69 and the Protocol.

Mr Hagel, I agree that interpreting the claims in the light of the description will place more of an emphasis on matters connected to Art 84 EPC. That is, it will become more important for the EPO to ensure that at least the distinguishing features of the invention are clear, or at least as clear as possible, from the wording of the claims alone.

For EPO examiners, this might not prove the most popular of developments, as it could significantly increase the time that they need to spend on Art 84-related issues. However, on balance, I think that would be a welcome development not only for patent applicants and proprietors but also for the general public.

Firstly, with one exception (adaptation of the description), there is evidence to suggest that the EPO’s current approach to assessing compliance with Art 84 EPC is rather lax, and is not at all in accordance with the high standards set out in the Guidelines:

https://www.patentlitigation.ch/productivity-vs-quality-at-the-epo-a-rare-glimpse-behind-the-curtain-thats-worrying/

Secondly, my experience leads me to believe that the EPO’s rather laissez-faire approach to assessing Art 84 EPC compliance leads to the grant of patents that create unnecessary FTO issues for third parties, with the consequence that third parties are forced to choose between tolerating unjustified restrictions on their FTO or going to the effort (and expense) of knocking back unjustified claim scope. Also, due to the unavailability of Art 84 as a ground of opposition, the latter option can be particularly challenging when the fundamental problem is a lack of clarity in claims as granted.

It seems to me that the EPO’s only answer to the problems created by such a laissez-faire approach is to insist upon a strict assessment of the “support” requirement when it comes to adapting the description to the claims. Whilst I do not wish to open that particular can of worms, I will point out that such an approach has inherent limitations. In particular, if the wording of the claims is unclear, aligning the description with that wording will not make the claims any clearer.

On the other hand, if the EPO and all judicial instances agree that the claims should be interpreted in the light of the description, third parties will be able to determine the scope of the claims with more precision. Whilst such determinations might require careful consideration of the disclosures of the description, I fail to see how that is any different to what third parties have to do now, given how national courts interpret patent claims.

Two thoughts:

1. Let us distinguish the statutory law of the EPC from the case law of the EPO. We can argue that the case law can change and develop, evolve, if you like, but we have to accept the statutory law for what it is. I like the way the EPO case law has evolved, and hope for further positive evolution. Let’s not argue on the basis that the case law is written in stone whereby further evolution is impossible. Instead, let’s argue how it can be further refined, by further evolution.

2. As to the extent to which the description can inform the person trying to divine the meaning of a claim, consider the following hypo, built around the word “eye”. The word “eye” has several meanings. A potato has an “eye” (a local depression in its otherwise smooth outer surface) , a needle has an “eye” (a hole), an aerial drone has an eye (a camera) and many mammals have an eye in each of two opposed surfaces of their head. My lay-drafted claim is a device to improve safety on the roads and is directed to a wing mirror for a road vehicle, characterised by a forward-facing eye and a rearward-facing eye. The description explains the problem and how the two extra eyes solve it. The prior art includes a) a wing mirror assembly (shaped a bit like a potato) with local depressions in its forward-facing surface and its rear, and b) a wing mirror with a small hole in each of those two opposed surfaces. Amending the claim, to clarify its meaning exposes it to Art 123(2) issues. Unamended, is it novel over the art? Yes or no? And why? Or, in other words, what does the claim “mean” when it recites an “eye”? What is the broadest “reasonable” construction of “eye” in my claim? Wide enough to refuse the claim for lack of novelty?

@MaxDrei

In your example with the word « eye », my answer is that a claim has to be interpreted as a whole. The interpretation of the word « eye » should take into account the other terms of the claim. The claim in your example is directed to a wing mirror for a road vehicle, this makes quite clear that the meaning of « eye » in the claim is necessarily related to optical devices, not to potatoes or needles.

As to the reliance on the description and drawings in claim interpretation, I think the question must not be formulated in a binary mode. The word »interpretation » needs itself an interpretation of its scope. If it is intended to encompass the initial requirement of a basic technical understanding of the words of the claims, it is obvious that the description and the drawings are necessary to gain understanding of the words of the claims. The reader of a claim unable to look at the description and the drawings is like a blindfolded person trying to imagine the facial features of a statue just from finger contacts. There is a good reason for the requirement to include the reference numerals of drawings after the terms of the claims.

Thanks FH. So, which is it? Do the prior art mirror assemblies with holes or local depressions lack any eyes? Or is it that the eye in the claim must be read (in the light of the description) as “optical eye”?

My position is that not every hole or surface depression counts as an “eye”. The prior art wing mirrors might have holes or depressions, but that does not mean that they have an eye and prejudice the novelty of the claim.

Suppose an ED at the EPO sees the wing mirror prior art, and sees the prior art as not prejudicial to novelty. Will it nevertheless require clarification of the meaning of “eye”? Will it raise objection that the claim offends Art 84, EPC and then object under Art 123(2) to whatever clarifying amendment I file?

Suppose the claim is granted and the EPO sees the wing mirror prior art for the first time. I hope it would take my position, that there are no eyes in the prior wing mirror assemblies.

Dear Max Drei,

Your example of the eye is at the core of the discussion. From the outline of the case, it appears that the applicant has given to the word eye a special meaning. As this meaning is better defined in the description, I am of the opinion that the definition given in the description should be brought in the claim. Then claim and description are then aligned with each other.

I would reserve a decision on N or IS depending on the amendment of the claim. Amending a claim for the sake of clarifying it, can indeed lead to a massive problem under Art 123(2). This is why the amendment of the claim has not merely the purpose of clarifying it, but to clarify it in the meaning of the description. This is the only way not to fall in an inescapable trap.

Max, I can agree with your point 1. However, I would add that the “refinement” of case law is not confined to mere further evolution but can occasionally necessitate a fundamental re-evaluation.

A fundamental re-evaluation is necessary when two criteria are satisfied.

The first criterion is that both the case law of, and the institutional thinking within, an organisation has become “path dependent”.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Path_dependence

The second criterion is that failings of, and inherent flaws in, current case law and thinking have created a critical juncture.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Critical_juncture_theory

The EBA has dealt with this kind of scenario before. That is, case law on formal entitlement to priority had become “path dependent”, in the sense that it invariably required proof that, prior to filing the subsequent application, the applicant had secured entitlement to claim priority from all applicants for the previous application. The trouble with this requirement is that it forced the EPO into positions where it effectively had no choice but to stray into areas where it has no competence (ie entitlement and contractual matters under national laws). The fundamental re-evaluation then came in G 1/22 and G 2/22, which reverses the burden of proof and sets an EPO standard (equating to the lowest standard under any national law), thereby avoiding any determination of matters under national laws.

The question is, do we also need a fundamental re-evaluation in connection with how the EPO interprets the subject matter of claims?

I think that there is ample evidence to support the theory that the EPO’s case law and institutional thinking has become “path dependent”. That is, the primacy of the claims seems to have become embedded at the EPO as some sort of immutable principle of patent law.

But are we now at a critical juncture? Reasonable minds can differ on this point. My view is that we are, and that this is evident from:

– the absurdities that arise when there is strict and consistent application of the EPO’s two different approaches to interpretation; and

– the incompatibility of the EPO approach with that applied by all courts of the EPC member states; and

– the fact that no other judicial instance of EPC member state has ever derived from the provisions of the EPC the principle of the primacy of the claims (as applied by the EPO).

The EPO can of course choose to keep their head down and keep ploughing the same furrow. But that will not solve current absurdities and incompatibilities, which will continue to raise their ugly heads.

@MaxDrei

It seems to me that if the « eye » can be considered to pertain to the area of optical devices when looking at the claim as a whole, the principle of the « broadest technically sensible interpretation » should involve that the meaning of « eye » has to be limited to optical devices and cannot encompass meanings pertaining to potatoes. Otherwise the interpretation would not be « technically sensible ». As a result, the meaning of « eye » in potatoes should be considered irrelevant and not novelty-defeating. Of course, the applicant could decide to amend the claim by replacing « eye » by another more specific term or adding to « eye » a limiting feature, providing there is support for the amenment in the description.

@Doubting Thomas

I am no chemical or pharma expert but I believe your proposal of a stricter approach of clarity would be an uphill struggle in the field of biotech/pharma and chemistry, where the key issue is the breadth of claims and claiming in the Markush format millions of specific molecules supposed to have a certain effect is common practice. Since there is typically no logical reasoning linking the desired effect to a specific molecule, the description contains specific examples with the result of tests relevant to the desired effect. But their number can only be very small compared to the number of molecules covered by the Markush format, simply because such tests take time and cost money.

So, FH, it seems that we differ, on what to do with the “eye” hypo.

I say that just because a local depression in a potato is an “eye” does not mean that every local depression can fairly be labelled as an eye. A local depression on the convex outer surface of a crash helmet (for example) is not an “eye”.

Likewise, not every hole in a housing of an object is an “eye” just because the hole in a needle is called an eye.

So, for me, looking at the cited wing mirror prior art, neither the depression nor the hole in the cited wing mirror housings is an “eye”.

So, the claim as it stands has novelty.

As to clarity, no claim is clear to a level of 100%. I say that the claim as it stands is clear enough, fit for purpose, and that the ED ought not to object to it under Art 84, EPC.

My hypo was intended to flush out how important it is to ascertain from the description a “context” in which to construe the claim and ascribe to it a sensible and robust meaning. It is pleasing how many reactions to my hypo I have gathered in this thread. But I am still waiting for the EBA to tell me how much influence the description shall have over a person who is engaged in the task of divining the meaning of a claim.

@ Doubting Thomas

What a pompous comment from an overinflated ego.

I can agree that the case law had it wrong with the validity of the priority claim. There is at least one more situation in which the case law had it wrong.

I personally was always ill at ease with the possibility of doubting the validity of the priority claim by the opponent for purely formal reasons. Those reasons were quasi exclusively raised against priority claims from the US. There would have been one way out: all the applicants of the US priority application file the subsequent European application, and the property of the subsequent application is transferred to the assignee after filing. It is good that the EBA introduced the rebuttable presumption of validity.

Sometimes applicants declare in the introductory part of the description, presenting prior art, as follows: “it is known that… ” without mentioning any precise pre-published document. There is a line of case law allowing to delete such a statement and the corresponding passage of the introductory part of the description, as it was considered “internal prior art”. This started with T 22/83.

In T 22/83, the deletion of original Figure 4, coupled with amendments to the introductory part of the description served to remove an objection to inaccuracy in representation of the state of the art, and was considered as an allowable amendment which does not contravene Art 123(2).

This point of view was challenged in T 1227/10. In line with T 22/83, the OD had decided that the deletion, during examination, of the original figure 1 and of the part of the description relating to this drawing, both of them indicating the illustrated embodiment as being part of the prior art, actually removed an erroneous statement of the prior art in the original application.

In opposition appeal proceedings, the board held that the deletion of original figure 1 labelled as prior art and of the corresponding part of the description in the original application, has modified the application in a way that the granted claim 1 includes subject-matter which was excluded from the originally filed invention, as it would have been understood by a skilled person on reading the whole original application on the date of filing. The board found thus that this amendment in examination infringed Art 123(2). I fully agree with T 1227/10 and disagree with T 22/83 and the decisions following it, e.g. T 2450/17. I would add that when an applicant states “it is know that”, this boils down to an implicit acknowledgment of a disclosed disclaimer.

I would however not allow myself to state that “The EPO can of course choose to keep their head down and keep ploughing the same furrow. But that will not solve current absurdities and incompatibilities, which will continue to raise their ugly heads.” This is beyond any decency.

Allowing a deletion which is in clear contradiction with in G 3/89 OJ 1993, 117, should not have happened, but I will limit myself to such a decent statement.

Your view is “that we are, and that this is evident from:

– the absurdities that arise when there is strict and consistent application of the EPO’s two different approaches to interpretation; and

– the incompatibility of the EPO approach with that applied by all courts of the EPC member states; and

– the fact that no other judicial instance of EPC member state has ever derived from the provisions of the EPC the principle of the primacy of the claims (as applied by the EPO)”.

As Max Drei, I am still waiting of the quotation of a TBA decision showing any absurdities as you claim.

What you want, is to allow applicants to give in the description a “customised” definition of a feature present in the claim. I call this, once more, a deliberate attempt of cheating.

You cannot force a reader of the claim to systematically look at the description, just because you want to confuse the issues. If the claim states the “customised” version disclosed in the description, then there is no obstacle for a national court to interpret the claim the same way the as the EPO does, and even extend the scope of protection according to the protocol.

In the case of “means + function” claims, which for devices allow the broadest scope of protection, or in case of an allowable intermediate generalisation, there is an absolute necessity not to stick only to the wording of the claim to decide whether it is allowable or not.

In the case of “means + function” claims, cf. GL F-IV, 6.5, it has to be immediately apparent to the skilled person that a skilled person would have no difficulty in providing some means for performing this function without exercising inventive skill.

This is acceptable even where only one example of the feature has been given in the description, if the skilled reader would appreciate that other means could be used for the same function. One example amplifier with discrete transistors = amplifying means.

T 274/14 is one example of an allowable functional definition. T 1575/17 is one example of a not-allowable functional definition. In both cases, the description has to be taken into account.

In case of second medical use claims under Art 54(5), the definition of the illness to be treated represents a functional limitation of the claim, which can only be considered fulfilled if the description discloses the corresponding necessary information.

An intermediate generalisation is as well acceptable, but there again, what is important and plays a determining role is how the entire content of the disclosure it is understood by a skilled, and not merely what results from a formalistic analysis of the description and/or the claims.

At least, the presence in the description of a plurality of possible embodiments, as well as a “covering” statement, can help to answer favourably the question of support for an intermediate generalisation. Examples of allowable intermediate generalisations are to be found for example in T 1906/11 or T 116/20. Not-allowable intermediate generalisations, based on the overall disclosure and hence on the description, are to be found for example in T 582/08 or T 1887/10.

T 335/22 is another example in which the description has been used to interpret the claims. If the claim is clear as such, then it is prima facie not necessary to rely on the description. On the other hand, “customisation” of claimed features renders necessary the recourse to the description. It is only the “customisation” of claimed features which renders necessary the recourse to the description, but this should not be allowed, and is considered allowable at the EPO. The description cannot be used to give a claimed feature a different interpretation, for instance more limited, of a claimed feature. My examples of the ventilator and the perforated layer are perfectly illustrating this stance.

It is thus a fallacy to allege that the primacy of the claims allows, or even forces, to disregard the description, so that only the claims are taken into account. Such a statement is not acceptable.

This is I hope what G 1/24 will bring. The rest are merely fanciful elaborations of a mind that refuses to apply the EPC in all its thoroughness. Come down to reality and do not consider yourself as knowing it better.

Do not wonder if further comments of yours might end in the trash bin.

The last comment of Anon Y. mouse went this way.

Enough is enough.

For the avoidance of doubt, and as I would not wish offence to be taken on the basis of a possible misunderstanding, the statement which seems to have caused offence has a meaning which should be understood as being along the following lines:

“The EPO can of course choose to keep their head down and keep ploughing the same furrow. But that will not solve current absurdities and incompatibilities, which will continue to crop up and cause problems”.

I had hoped that this would be an ideal forum for a rational and reasoned debate on the strengths and weaknesses of different interpretations of the EPC. Whilst I have been encouraged by the contributions of some commentators in this regard, I am sad to report that, on balance, I can only conclude that my hopes have been dashed.

@ Doubting Thomas

This is a reply to your two last comments.

There is no misunderstanding whatsoever. It is not a single statement which has caused offence, but the overall tone of your last entries.

That you have not taken position on the examples of case law I have quoted, is not surprising, since for you case law has gone astray. I have to note that you have not yet shown one decision of the boards, or from a national or supranational court, in which the “primacy of the claims” has led to absurdities and incompatibilities.

You do however insist on your point of view and from only a purely theoretical approach, you come to the conclusion that the way the EPO and its boards handle the cases, necessarily implies absurdities and incompatibilities.

The present blog is an ideal forum to discuss the strengths and, for you, the alleged weaknesses of different interpretations of the EPC. It is you who has spoiled the discussion with your apodictic attitude. For your information, I have deleted the last comment from Anon Y. mouse, as it was worse than yours.

Your hopes have not been dashed. It turns out simply that your point of view fails to convince, and I am not the only one. It is not by repeating, ad nauseam, your point of view, that it will become more convincing.

I am convinced that, with claims properly supported, by the description, and not simply mentioning features in the claims, which have to be checked against the description, that all the actors in IP, will be satisfied. Third parties faced with patents, and the threat of infringement, as well as proprietors wanting a fair retribution for their contribution to the art will be satisfied. Those applicant’s/proprietor’s not wanting to abide by the rules of the game, might be disappointed, but it is their problem. Neither will be national courts or the UPC hindered in their application of Art 69 and of the protocol to determine the scope of protection given by the claims.

There is a post coming, in which reading of the claims in the eyes of the skilled person, does not need to resort to the description. The description is merely there to confirm the reading of the claim. But what matters is the claim.

As the thread is still alive I want to clarify one thing in my “eye” hypo. Does the claim belong to the category clear per se? Or is it a claim that needs recourse to the description for its clarity to emerge? I say the former (and I still think I am right). Reasonable minds differ, on such questions.

@MaxDrei

I agree that you are right. The word “eye” in its different contexts (potato, etc) has a meaning which is inseparable from its specific context.