EP 2 434 850 B1 relates to input/output circuits and devices having physically corresponding status indicators.

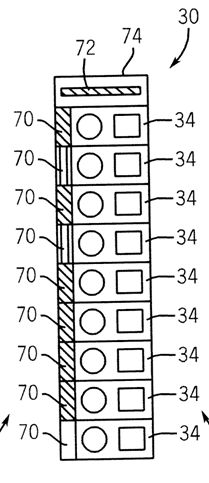

Claim 1 of the patent defines that one (first) of the status indicators is placed directly adjacent to the terminal it is associated with, while the other (second) comprises a portion surrounding the opening of its associated terminal.

Brief outline of the case

The OD decided that claim 1 as granted contained added matter, as did claim 1 of AR1.

The patent was maintained according to AR2.

Both proprietor and opponent appealed.

As there was no added matter in claim1 as granted, and it was novel and inventive, the board set aside the decision of the OD and maintained the patent as granted.

The case is interesting in that it defines the objective technical problem (OTP) formulated in the context of the problem-solution approach (PSA).

The opponent’s point of view on IS

The opponent was of the opinion that the features distinguishing claim 1 from D7= EP 1 315 248 A1 were to be assessed separately as no synergistic technical effect was apparent.

Those were

- two status indicators displaying different statuses

- the second status indicator comprises a transparent or translucent portion which surrounds the terminal opening

Two status indicators

Regarding the two status indicators displaying different statuses, the opponent argued that if it were considered that both indicators in D7 displayed the same status, they could be seen as one status indicator corresponding to the second status indicator of claim of the patent.

In that case, the feature missing from D7 would be another (first) status indicator, adjacent to the terminal opening, which was capable of displaying a status which was different from the one displayed by the existing status indicator.

According to the opponent, the technical problem solved by this distinguishing feature was how to display a second status of the terminal in the I/O block of D7. The skilled person would have thus sought a position in the I/O terminal block to place a second indicator to display a second status.

Given the structure of the block, it would have been obvious to place an additional indicator next to the terminal, i.e. “directly adjacent” to the terminal.

The second status indicator surrounding the terminal opening

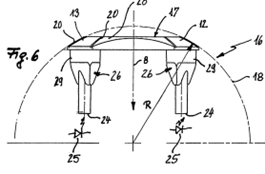

The opponent pointed to the description of D7, according to which the front face of the surface of the terminal block was curved and the purpose of having the two indicators 12 and 13 was to make them visible from both sides of the terminal block

It would thus have been obvious for the skilled person to increase the size of the indicators and if they wanted to improve visibility from all sides even further.

According to the opponent, in such a case, the combined indicators and would correspond to the second status indicator, while another status indicator, corresponding to the first status indicator of claim 1 would have been placed directly adjacent to the terminal, also in an obvious manner.

The proprietor’s point of view on IS

According to the proprietor, the distinguishing features provided a synergistic technical effect and should be assessed together for inventive step.

There was nothing in D7 indicating that the two indicators were capable of displaying different statuses. The opponent’s argument was based on hindsight. The description of D7 was also clear that the size of the two status indicators was limited and there was no motivation for the skilled person to extend any of them around the terminal opening.

The board’s decision

The parties did not agree whether or not these features provided together a synergistic technical effect over D7. For the sake of argument, the board assumed that the distinguishing features did not provide a synergistic effect and are to be assessed separately with regard to IS.

Two status indicator

The board did not follow the argument of the opponent, mainly because it does not accept the formulated technical problem. This formulation of the technical problem takes for a given that the skilled person wishes to display a second terminal status of the terminal in D7 and that the only problem is how to do that. However, there is nothing in D7 that indicates that there is a second status to be displayed.

D7 does not envisage the display of any second status different from the status it already displays. Hence, it cannot be accepted that the only problem the skilled person would be faced with is how to display such a second status.

In the board’s opinion, in order to arrive at the claimed invention, the skilled person when starting from D7 would first have to find a motivation for displaying a second status of the terminal, then to find a way to modify the described light sources such that they were capable of displaying different statuses and would only then have to start contemplating where to place an additional status indicator.

The board considered that such activities go beyond what could be considered obvious for the skilled person in the present context.

The second status indictor surrounding the terminal opening

The board held that the formulated technical problem of improving the visibility of the status indicator is not related to the claimed invention. The terminal block of the claimed invention has no curved front face and the problem of rendering the indicators better visible from all sides does not arise.

In the present case, the terminal block of the claimed invention has no curved surface and there is no technical advantage related to the visibility of the status indicators from all sides.

The problem of improving the visibility of the status indicators concerns only D7 and the I/O block it describes, but is not a problem to be solved which relates to any technical effect the distinguishing features provide to the claimed invention with respect to the prior art. The board, hence, finds the opponent’s argument not convincing.

The board added that the OTP formulated in the context of the PSA should stem from a technical effect the distinguishing features provide to the claimed invention with respect to the closest prior art and not from a possible improvement of the prior art itself.

Comments

In general, a patent can be considered as a technical solution to a technical problem, which can be considered as the “subjective” problem starting from a given piece of prior art known to the applicant. The “subjective” problem can, but not necessarily be to improve an existing prior art. Sometimes the “subjective” and the “objective” problem can coincide.

With a different piece of prior art, when applying the PSA, the notion of OTP comes into play.

In the present case, the board simply reminded that the OTP stems from the technical effect of the difference with the prior art and not from the mere wish of improving the prior art.

The opponent’s argumentation is a good example of ex-post facto argumentation. Without artificially bringing in an absence of synergy, the opponent’s argument would have failed from the outset.

Comments

9 replies on “T 646/22 – Correct definition of the objective technical problem”

Daniel, I stumbled over one sentence in the Board’s decision and perhaps you could comment.

In para 4.4 the Board imagines the hypothetical skilled person starting from D7. That person, says the Board:

…would first have to find a motivation for displaying a second status…

That wording seems to me somewhat unfortunate, even misleading. I think that the skilled person is not to be credited with an active urge to “find” any motivation. Rather, I imagine it as the job of the state of the art to give the (passive) skilled person a motivation to modify D7 in such a way that it delivers a second status.

Also, how does this case fit with the case law concerning inventive activity lying in the perception of the problem, even in cases where solving the problem is obvious once the problem has been perceived? Would it not have been easier for the Board, here, to decide the case on the basis that invention lay in perceiving and announcing the problem that the invention has solved?

Dear Max Drei,

I agree with you that the statement in para 4.4 that the skilled person “…would first have to find a motivation for displaying a second status…” is at least unfortunate.

On the other hand, this corresponds to German case law, or at least how I understand it. In German case law, deciding upon the presence of inventive step depends first on whether the skilled person has to find a reason to modify the existing prior art. If there is no reason.

I refer here to an article of Mr Deischfuß published in GRUR Patent 2024, 94 in which a comparison is made between the way the German Federal Patent Court (BGH) and the Boards of Appeal of the EPO assess inventive step.

In Point 38-41 of this article, the author explains that in order to for the BGH to positively decide on inventive step it needs, as a rule, additional impulses, suggestions, hints or other reasons beyond the recognisability of the technical problem in order to give a technical solution to a technical problem in order to set the skilled person on the way to the invention. In this respect, the author cites the CLA 10th edition, 2022, ID.5.

The problem is that in ID.5 very old decisions are quoted, i.e. T 219/87, T 455/94 and T 414/98. The quote has the purpose to show that the case law of the BGH is not fundamentally different from that of the boards. I beg to strongly disagree, and fully follow your point of view.

I have not seen the concept of the skilled person needing a hint or a push, in other words a motivation for solving a technical problem, in recent decisions of the boards, but the present one. This is clearly a specificity of German case law and does not tie up with the board’s general case law on inventive step.

As far as the invention residing in the formulation of the problem, I found very few decisions of the boards going along this line and acknowledging a “problem invention”. See T 109/82, T 2/83, T 135/94, T 345/94, T 1236/03, T 1344/06, T 764/12, T 659/15 and T 1/18.

In comparison, in the less than 20 cases in which the applicant/proprietor attempted to defend inventive step by claiming a “problem invention”, this was denied by the boards. In view of the thousands decisions of the boards in matters of inventive step, “problem inventions” are thus extremely rare. During my active time, I jokingly used to consider “problem inventions” an invention of representatives.

Thanks, Daniel, but I am still confused. You write that the OTP stems from the technical effect. That’s my understanding too.

So I searched through the Decision to find out what the Board identified as the technical effect. Until we have fixed what is the technical effect, we can’t announce what is the OTP. Until we fix the OTP we can’t decide whether the claimed subject matter is or is not inventively patentable at the EPO

But I couldn’t find it. Can you? Where, please, in the decision text do I find it?

But wait. Perhaps for reasons of judicial economy, the Board held itself back from announcing the technical effect. For the Board, it sufficed to announce that the Opponent’s attack failed and therefore, given the presumption of validity of already granted patents, the opposition failed. No need to go any further. No need for it to spend time analysing what is the true technical effect.

Is that it? Perhaps, especially given any tension between the jurisprudence of the EPO and that of the German courts, better not scratch the sensitive spot?

Dear Max Drei,

When looking at the decision, the board reminded in Reasons 4.5.1, second §, that the OTP corresponds to the technical effect obtained by the features distinguishing the claimed invention from the prior art.

I am less convinced with the sentence which follows: “In other words, these distinguishing features should provide a technical advantage to the claimed invention that the prior art has not.” If the OTP boils down to find an alternative, then there is no distinguishable effect or advantage. The way to achieve the same effect is simply different, but still can be inventive.

In the present decision, what seems to have confused the issue, is that the board accepted the point of view of the opponent, that the differing features do not have a synergy effect. But then, the board appears to argue as if there was a synergy. In the absence a synergy, partial problems come into play and then we have two partial OTP. This logical conclusion is missing in the present decision.

I do not think that the board merely wanted “to announce that the Opponent’s attack failed and therefore, given the presumption of validity of already granted patents, the opposition failed.” In such a situation, the decision would actually not be reasoned.

That there is some tension between the jurisprudence of the EPO and that of the German courts, and I guess in the future with the UPC, as the latter will most probably follow the German line, is best exemplified in the Article of Deichfuß I mentioned.

In this article, the author is trying desperately, and again all odds, to show that, after all, both jurisprudences in matters of IS are not so different as it might look at a glance. I was anything but convinced by this article. One thing which appears acquired, is that at the EPO the skilled person will rarely be defined, as technical knowledge is in-house.

There is indeed a sensitive spot, but a lot will depend on what the EBA will say in G 1/24. This is not at all dealt with in the article. The author merely mentions that some BA rely on Art 69(1) and some not.

Thanks, Daniel. I too found disappointing the decision’s “reasoning” on the question: synergy Y/N. For the reasons you give.

As to whether a “mere alternative” delivers a “technical” effect, is it not effect enough, that the invention delivers a way to achieve a desirable result using means other than those taught by the prior art. Suppose there is a shortage of the prior art “means” (catalyst from China, perhaps) and the invention provides a way to finesse out of that shortage. For me, that is both “technical” and a worthwhile, creditable, patentable “effect”.

As to when a decision contains enough reasoning, do you not think that it is enough to provide rock solid reasoning why the Opponent’s attacks all fail? Reasoning why the claim in suit is inventive strikes me as going beyond what is needed to dispose of the case, fully supported by adequate reasoning.

As to whether the UPC adopts the EPO approach, or that of the courts in Germany, what chance does a mere Patent Office have, against the collective wisdom (and confirmation bias, and not-invented-here syndrome) of all the judges of the highest courts in the leading UPC jurisdiction.

A shame. But there it is. These days, in so many other fields, the win goes not to the side with the better argument but to the one with the most power. We do it this way. Why? Because I say so. Because I have always said so.

As we all know, and as Albert Einstein explained, one of the most difficult things for an intelligent human to do is to admit, first to themselves, and then to their peer group, a change of mind.

Dear Max Drei,

I agree with your example with the shortage of means. In such a situation I would be inclined to say that the OTP is not merely an alternative. It rather seems to me that the OTP would be to achieve the same result in the absence of means which were usual in the field. For me as well, that is both “technical” and a worthwhile, creditable, patentable “way to achieve the same result with other means”.

The EPO and its boards have dealt with the validity of patents for a much longer time than the UPC has done and will ever do. It certainly is the wish of people like Sir Robin Jacob and all the proponents of the UPC, that the EPO’s boards of appeal will follow the case law of the UPC. Nothing is more sure.

As the two deciding bodies have no link whatsoever, besides an exchange of decisions, if there is a political will at the EPO to keep its original way of handling validity, then there is no reason that the EPO will for instance adopt the way of assessing IS along the German/UPC line of thoughts. The political orientation is normally given in the Administrative Council of the EPO, and there are quite a few powerful states in it, than the mere EU member states.

Depending on what will come out from G 1/24, the likelihood that diverging decisions between the UPC and the EPO occur is far from negligible. If both jurisdictions revoke a patent, then nothing will happen. If one revokes and the other not, then we will have a mess.

If the EPO revokes, and the UPC maintains, we have a first critical situation. If the EPO maintains and the UPC revokes we have a second critical situation. Where will the proprietor or the infringer will recover the losses due to the diverging decisions? It’s easy for the CoA UPC to say that, for the sake of harmonisation, the second deciding body should follow the first decision, as in view of the procedural delays built in the EPC, the UPC will always decide first. I do not call this harmonisation, but judicial imperialism.

In view of its broader geographic range, the EPO has a much broader radius of action than just the UPC contracting states, although the UPC wants desperately to extend its long arm to non-UPC contracting states. The recent BSH/Electrolux decision of the CJEU has given the UPC a powerful tool when it comes to EU member states.

I am not sure that the UPC has such a strong power as it thinks. It would like to be a giant, but this giant sits on a very shoddy base. I think here of the fiddling which has occurred after Brexit. I will not get tired to repeat that the UPCA does not comprise an exit clause, contrary to the EPC.

The Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties provides mechanisms in order to deal with such a situation, but they have all be superbly ignored by all the supporters of the UPC. The lure of money by national judges wanting a post at the UPC and that of internationally active lawyers firms has brought such, actually well legally educated, people to ignore what a second year law student learns in detail.

Not sure, Daniel, that there is anything I can add. But the thought occurs, that here (as is so often the case, elsewhere):

“The piper calls the tune”.

In other words, he who pays the musicians gets to designate what music they play.

In human affairs, this is the default, that which is inevitable, unless the little people act collectively against those with all the power.

Which leaves me thinking that there must be a corresponding expression in French, no?

Oops. The expression is in fact “He who pays the piper calls the tune”. Sorry, readers, for my undue haste to post my reply.

Dear Max Drei,

I have never disguised that for me, the UPC is one big and successful lobby action by circles who were interested in making even more money: internationally active lawyer’s firms. When setting up the RoP, with the help of some judges, they made sure that the time limits are such that they increase the representation fees, above an already far from “normal” level.

When you see that in the Hanshow case, the amount of recoverable fees in two instances is around 300.000 € for a refused PI, you can easily calculate that, for the claimant having lost in two instances, it could be double this amount.