EP 3 474 205 A1 relates to the energy efficient delivery of mail items.

Brief outline of the case

The application was refused for lack of IS and lack of clarity.

The board confirmed the refusal.

In the present entry we will concentrate on the MR.

Further prior art cited by the board

Since D1 to D3 cited in the examination proceedings disclose few details of claim 1 and these documents appeared unsuitable as CPA, the board referred to more suitable citations from proceedings relating to family members of the present application.

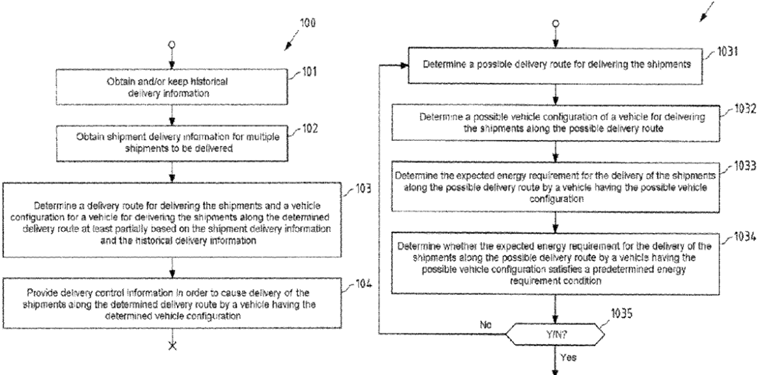

D4 cited in the Chinese grant proceedings describes a method for determining optimal delivery routes and vehicles based on historical data such as delivery routes, fuel consumption, traffic information, etc..

D4 thus has most of the features in common with the invention.

D4 only does not disclose that the energy consumption of a delivery route is calculated in advance, but the total cost of delivery, which usually includes energy costs.

D5, also from the Chinese grant procedure, teaches to improve energy efficiency by calculating the energy consumption of a route. In particular, D5 also teaches to adapt the energy consumption to the nature of the route, such as gradients and road surface.

It was undisputed that D4 is the CPA. D5 is used to assess IS of the ARs.

The difference between claim 1 and the disclosure of D4 is therefore only that, as a cost factor of the total cost also, the energy requirement is determined.

The applicant’s point of view

According to the applicant, the effect of this difference is that the energy requirement can be minimised by selecting the least energy-consuming delivery route from a large number of possible delivery routes.

The applicant argued that D4 is primarily focussed on business purposes. As an alternative solution to the proposed solution, a “reverse auction”, i.e. the customer selects from several offers submitted in advance by transport companies, is proposed.

This economic solution would lead the skilled person away from the technical solution proposed in claim 1, i.e. a minimisation of energy consumption.

The board’s decision on IS

In the context of the problem-solution approach, the skilled person must usually first work out the teaching of the CPA.

For the board, if the skilled person arrives at the claimed solution simply by working out this teaching, the working out of the teaching of the CPA can be regarded as the OTP.

Applied to the present case, D4 leaves open how the total costs are determined. Only the concrete way of determining the total costs in D4 is regarded has the effect of the distinguishing feature. Thus, it follows that the OTP is to carry out the teaching of D4.

The skilled person would automatically arrive at the subject matter of claim 1 when working out the teaching of D4. D4 teaches the calculation of different routing options and route segments as well as their costs and how to minimise the costs.

When calculating the cost of the various routing options, the energy consumption must necessarily be determined in order to determine the cost share of energy/fuel. Consequently, D4 alone teaches the determination of energy consumption if the skilled person is to work out the procedure described in D4 and minimise the total costs. Under these conditions, the skilled person must, among other things, necessarily also calculate and minimise the energy costs.

The board was also of the opinion that the skilled person, would necessarily already arrive at the solution according to the claim by working out the teaching of D4. The fact that a “reverse auction” is proposed as an alternative solution in D4 was therefore irrelevant.

The board was further of the opinion that the determination and reduction of energy costs and, in particular, the selection of a route with low energy requirements over a route with high energy requirements is part of CGK.

D5 demonstrates this CGK. D5 teaches, among other things, how to determine and minimise energy consumption and emissions when calculating a delivery route.

Claim 1 of the MR thus lacks IS.

Comments

Further prior art of the board

By virtue of Art 111(1), a board is perfectly entitled to bring in new prior art in appeal upon examination.

It is however not common that the board goes as far as to look what has happened during examination of family members, and certainly not from the Chinese procedure.

By the way, a patent has been granted in the US=(US11514392).

A new definition of the OTP

The present board has added a new feature to the well-known PSA: simply carrying out the teaching of the CPA represents the OTP, without looking really at the difference and the effect of the difference.

It will have to be seen if this decision is a one off and if other boards will adopt it as well.

Lack of IS

In T 1806/20, commented in the present blog, it was held that delaying the delivery of rain-sensitive parcels until it stops raining is not technical.

In the present case, minimising the costs by choosing a route with low energy requirements over a route with high energy requirements, does not seem technical either. And it does not appear, in the breadth of the claim, that it is inventive, although plenty of technical means are used.

T 1737/21

Comments

2 replies on “T 1737/23 – A new variant in the definition of the Objective Technical Problem in applying the PSA”

An abundance of recent BOA cases implementing the “objective technical problem” (OTP) shows that this artificial notion is fraught with issues and it might be seen as another opportunity for BOAs to squabble. It relies on the closest prior art (CPA) and technical effects achieved by the claimed subject matter over the CPA, but the CPA is a moving base, as illustrated in T 1865/22.

The PSA is a laudable effort to minimise hindsight in the assessment of inventive step, based on the welcome acknowledgment by the EPO that the search of prior art is inevitably based on the knowledge of the invention. But when the CPA was not known to the applicant before filing, there is a real risk of hindsight-guidance in the definition of the OTP. In addition, the restrictions laid out in G 2/21 to the submission of post-filing data as evidence for a technical effect vs. the CPA seem unfair, when the applicant was not aware of the CPA before filing (T 2465/19).

The “new variant” you refer to (T 1737/23) adds a layer of perplexity.

The discretion of the BOA in the late choice of the OTP raises another issue, as shown in the EBA decision R 8/19.

Judging the tree from its fruit, the artificiality of the OTP is evident when considering that the OTP has been defined in many cases as the provision of an “alternative solution”. This definition is only negative and technically meaningless. It is only relevant to novelty, certainly not to inventive step (T 687/22).

The UPC also applies a problem-solution approach, but it only requires a starting point to be “realistic”, there is no need for it to be the “closest”, and there is no OTP, the problem is defined in the light of the original application.

Mr Hagel,

I have difficulties in following your point that T 1865/22 shows that the “CPA is a moving base”. In this case, there was only one CPA, i.e. D7. Since there was no improvement over the prior art, the OTP was defined as a mere alternative. No improvement actually means that no effect shown by the differences with respect of the CPA. This way of defining the OTP is well enshrined in the case law of the boards. The board actually did not accept the reformulation of the OTP suggested by the proprietor. This has nothing to do with the CPA being a moving base.

The purpose of the search is to reveal PA which was not known to the applicant when filing an application. That this PA might show the invention in a different light is to be expected, otherwise no search would be needed. The CPA as defined in the PSA is by essence not known to the applicant before filing.

That the CPA has to be a realistic prior art, has been added over the years, but did not change the established way of defining it.

The PSA has been often criticised by arguing, like you do, that it could introduce a real risk of hindsight-guidance in the definition of the OTP. This risk might exist, but I have not yet seen a decision in which a board has deliberately misapplied the PSA and came to an OTP which bears no relationship with the claimed invention

In T 2465/19, the board held that, both the application and D1 have the same aim, and the recombination-inhibiting layer 57 of D1 has the same general function and effect as the corresponding current shifting region of the application. The board further noted that the technical effect of an invention over the closest prior art need not be explicitly stated in the application, as long as it is derivable from the original application, in particular since the closest prior art may not have been known to the applicant when drafting it (see also decision G 2/21, Headnote II. The mention, in T 2465/19, of G 2/21 has nothing to do with the core of the latter, and is nothing new when assessing IS according to the PSA.

In R 8/19, the definition of the OTP has played a role, but it cannot be concluded that the definition used showed any form of hindsight in its definition, as the petition was rejected as not being clearly allowable.

In T 687/22, the board and the proprietor differed on the definition of the OTP. In one part of the proprietor’s argumentation it defined the OTP as “providing for an alternative modification of the resulting signal based on the signal from the ear-canal microphone”. The board noted that “Regardless of the extreme breadth of that problem which alone happens to render it invalid, a modification introduced solely for the sake of differentiation from the prior art simply means that, at most, the novelty requirement of Article 54 EPC is met. This does however not guarantee compliance with Article 56 EPC. To be considered “not obvious to a person skilled in the art”, such a modification must, as a prerequisite, yield a discernible technical effect that credibly solves a technical problem”. The board never defined the OTP as being “an alternative”, so that it is difficult to follow your argumentation on this point.

I agree with you that the UPC uses a kind of PSA, which however differs from that of the EPO. The CPA has to be realistic, but this is also the case of at the EPO. The problem is indeed, the one originally disclosed, but when starting from a different CPA as that from the applicant, the argumentation on IS is then as “artificial” as that of the EPO.

It is interesting to note that LD Düsseldorf, Decision of 14.01.2025, UPC_CFI_16/2024 – Ortovox v. Mammut, EP 3 466 498, came to a conclusion diametrically opposed to that of the Swiss Patent Court with the same prior art. The LD Düsseldorf held the patent valid and infringed, whereas the Swiss Patent Court considered the patent invalid. The patent has not been opposed at the EPO.

The CD Paris, Decision of 27.11.2024, UPC_CFI_308/2023 – NJOY v. VMR, EP 3 456 214, revoked the patent for reasons which were anything but convincing. It used common general knowledge without any proof of it and alleged that it was obvious to transfer a window from the mouth piece of a cartridge into the side of a container receiving the cartridge. The same patent was maintained in amended form by the OD. I then rather follow the PSA of the EPO.