The patent relates to an apparatus for restoring blood flow in occluded blood vessels, particularly occluded cerebral arteries.

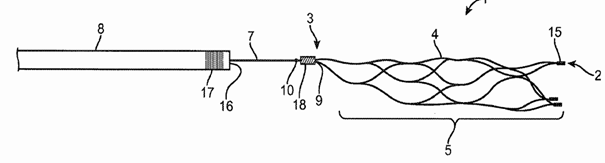

The important feature relates to “a connection point (9), at which the tapering portion converges, located at a proximal end (3) of the tapering portion, the tapering portion permanently attached to the push or guide wire (7) at or adjacent to the connection point (9)”;

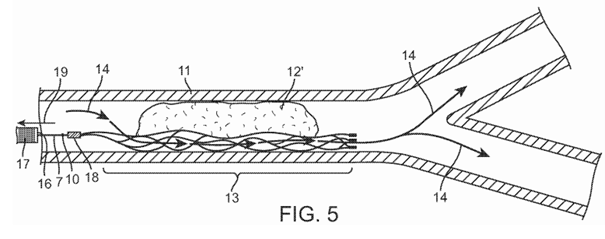

The flow is restored in that an opening is created next to the thrombus and once the opening is created, the thrombus is pulled away.

Brief outline of the procedure

The OD rejected the opposition and the opponent appealed this decision.

The board held that claim 1 as granted was lacking N over D4=US 2005/0209678 (1st X in ISR/EPO).

The discussion of whether or not D4 was novelty-destroying for the subject-matter of claim 1 focused on the question of whether D4 disclosed a permanent attachment of the tapering portion to the push or guide wire.

It was undisputed that the remaining features of claim 1 were disclosed in D4.

The opponent’s point of view

The present patent did not include a definition of the term “permanent attachment”, which was used only one single time (column 5, lines 17 to 18) without any further explanations.

The device of D4 was suitable for removal of a thrombus in a blood vessel, as acknowledged by the present patent. In order to be used for this purpose, the guide wire had to be permanently attached to the implant such that tractive and shear forces could be transmitted. If this were not the case, it would not be possible to move the device of D4 back into the catheter, as mentioned in paragraphs [0009] and [0013].

The connection between the guide or push wire and the mesh structure according to D4 could be detached by applying electrical energy to an electrolytically corrodible separating element. Releasing this attachment required additional measures and equipment, in particular a power source and an electrode, which was to be placed on the surface of the body.

Hence, the connection between the guide wire and the stent of D4 was permanent for as long as these additional measures were not taken and no electric current was applied to the connection. When using a device as claimed or as described in D4 for removal of a thrombus it was not necessary to connect a power source for electric current to the separating element or to place an electrode on the surface of the body. Hence, during the whole procedure of thrombus removal the connection between the guide wire and the device would be unaffected and would remain intact. Therefore, the connection had to be considered to be permanent.

For the opponent, “permanent” could not be regarded as contrary to “releasable“.

The proprietor’s point of view

D4 disclosed a medical implant that was introduced into the vasculature by a guide wire. Since the implant had to stay inside the body of the patient, it was essential for the connection between the guide wire and the implant to be detachable (paragraphs [0020] and [0016]).

The literal meaning of “permanently attached” was that the parts were attached in a permanent manner, i.e. the attachment was configured to last forever without already including means for ending it. Unlike the releasable attachment of D4, a permanent attachment was not configured – if used for the intended purpose – to be released.

The person skilled in the art was aware of the distinction between permanent and releasable attachments, as – in the technical field of treating blood vessels – releasable devices were known requiring means for disconnecting the treatment device (stent) from the positioning device, i.e. the guide wire and, in contrast, permanently attached devices not comprising such disconnecting means were also known.

The meaning of “attached” and different ways of attaching the treatment device to the positioning device were disclosed in the prior art, distinguishing between permanent and releasable attachments.

Moreover, using “permanently” together with “attached” only made sense if the term “permanently” further specified the properties of the attachment such that certain attachments were thereby excluded.

For the proprietor, the description of the patent defined the terms “permanent” and “releasable” as mutually exclusive. In the patent it was stated that the connection in D4 was releasable, while the connection according to the invention was described as permanent.

Furthermore, the releasable connection shown in Figures 19a and 19b was disclaimed as not in accordance with the invention. On page 7, lines 25 to 26, the application as originally filed distinguished between a permanent attachment and a non-permanent attachment, which included means for releasing the connection. The statement in paragraph [0010] that the drawings “illustrate exemplary embodiments of the invention” did not apply to these figures.

If the connection contained means for releasing the attachment, such as in D4, the connection would last until the user activated the means for releasing the attachment, i.e. not necessarily forever. Therefore, this was not a permanent attachment, but a releasable attachment, which did not fall under claim 1.

Moreover, the term “permanent” was not used in D4 for the connection between the stent and the guide wire.

Request for a referral to the EBA

In view of T 1473/19, taken by the present board in a different composition, the proprietor requested that the following questions concerning claim interpretation be referred to the EBA.

1. When interpreting a claim for assessing its compatibility with Article 54 EPC (Novelty) and the parties have presented (at least) two distinguishing alternatives, could the Board select one of these alternatives without any evidence?

2. In case that the originally filed application contained disclosure for two alternatives, the applicant selected one of the two alternatives to limit the claim and deleted the non-selected alternative to align the description with amended claims, is it a reasonable claim interpretation that the term used for the selected alternative is interpreted to cover also the non-selected alternative?

3. In case that neither the description nor the drawings of the granted patent contain support for one of the alternatives, would a prior art document of an unrelated applicant form evidence for the understanding of the person skilled in the art in the relevant technical field?

The board’s position

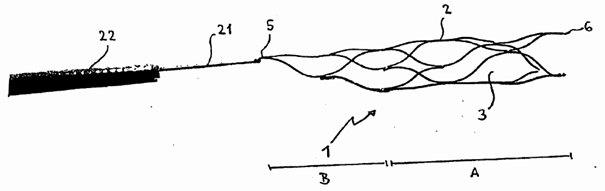

It is undisputed that D4 discloses a mesh structure forming a medical implant (stent) 1 with a tapering portion that is connected to a guide wire 21 (Figure 5), and that the mesh structure is suitable to engage at least a portion of the thrombus to form a removable, integrated apparatus-thrombus mass. It is mentioned in paragraphs [0014] and [0032] of the present patent that the apparatus of US 7,300,458, which is the granted patent to published application D4, may be employed for the methods described in the patent.

According to the established case law, patent claims must be interpreted through the eyes of the person skilled in the art, who should try – with synthetical propensity – to arrive at an interpretation of the claim which is technically meaningful and takes into account the whole disclosure of the patent (see Case Law of the Boards of Appeal, 10th edition 2022, II.A.6.1, first paragraph).

In the present case, both parties took the description of the patent into account to arrive at their differing interpretations of the expression “permanently attached“. This is in line with the approach taken by the present board in a different composition in decision T 1473/19, Reasons 3.15, commented in the present blog, according to which the principles of claim interpretation as set out in Art 69 and Art 1 of the Protocol on the Interpretation of this provision are to be applied in proceedings before the EPO.

Claim 1 itself neither defines nor specifies the term “permanently attached” further, either in terms of constructional features or in terms of the conditions under which the attachment is maintained. This matters insofar as the primacy of the claims under Art 69(1), first sentence, limits the extent to which the meaning of a certain claim feature may be affected by the description and the drawings, cf. T 1473/19, Reasons 3.16.1.

In the board’s view, the person skilled in the art understands the term “permanently” in claim 1 as characterising the attachment of the tapering portion of the implant to the push or guide wire with regard to how long this attachment will last. Therefore, this feature is arguably limiting to the extent that it requires the attachment to last a certain amount of time. However, the required duration or durability of the attachment is not specified further anywhere in the patent, either in the claims or in the description.

The board opined that in the physical world, nothing lasts forever in its current form. Furthermore, a physical connection can always be detached if an appropriate external force is applied.

The board construed the term “permanently” in claim 1 to mean that the attachment must last long enough to allow reliable extraction of a thrombus by pulling on the guide wire.

Contrary to the proprietor’s allegation, this meaning does in the board’s view not already follow from the word “attached” itself, since it is possible – if a use according to the patent is not intended – to realise an attachment that does not last long enough to allow reliable extraction of a thrombus by pulling on the guide wire.

However, even if the meaning as described above already followed from the word “attached” itself, it would not change the board’s interpretation of claim 1, as it is – contrary to the proprietor’s assertion – quite possible that a certain word in a claim does not have any limiting effect of its own.

The catchword of the decision reads as follows:

“Under Article 69(1) EPC the description and the drawings can only be used for interpreting features which are already present in the claims, but not for adding further – positive or negative – claim features or for replacing existing claim features by others (Reasons 2.15).

The application as filed usually cannot provide guidance for interpreting the claims of the patent as granted (Reasons 2.16).

A board of appeal is not limited to the claim interpretations advanced by the parties but may also adopt a claim interpretation of its own (Reasons 3.4.2).

Relying on documentary evidence is not a precondition for the adoption of a certain claim interpretation by a board of appeal (Reasons 3.4.3).

Request for a referral to the EBA

The request for a referral was dismissed by the board.

Without going much into details, the board held that the first question suggested by the respondent appeared to be based on several erroneous assumptions. In its reply the board referred to T 1473/19.

For the board, the second question does not concern a “point of law of fundamental importance” within the meaning of Art 112(1), which would be “relevant to a large number of similar cases“. In addition, the assertion that “the applicant selected one of the two alternatives to limit the claim” indicates that the second question starts from the assumption that claim 1 as granted indeed excludes releasable mechanisms.

The third question formulated by the proprietor essentially concerned whether, and if so, under which conditions, a prior-art document can be used as evidence for the understanding of the person skilled in the art in a certain technical field. This question could be answered by the board itself without doubt and thus without needing a referral.

Comments

When commenting T 1473/19, I noted that wanting to always interpret the claims in the light of the description is the usual way to deal with claims at the German Federal Court (BGH).

It was therefore debatable whether this approach should be taken over by the EPO, even with the proviso expressed in T 1473/19 that the primacy of the claims limits the extent to which the meaning of a certain claim feature may be affected by the description and the drawings.

The present decision does not bring a change of opinion in this matter, and the situation should actually be clarified by the EBA.

When a claim specifies that two pieces of a device are “permanently attached’’ it clearly and unambiguously means for the reader willing to understand, and not willing to misunderstand the claim, that by essence they are not to be released during a normal use of the device. That in real life a physical connection can always be detached if an appropriate external force is applied is in the present context beside the point.

I would like to draw the attention to the board to T 1431/06 which dealt with tube couplings. In claim 1 it was specified that a specific cap “cannot be unscrewed”.

The description of the patent as granted did not support interpreting the expression “cannot be unscrewed“ in an absolute sense of “cannot ever be unscrewed under any circumstances“.

Such an absolute interpretation was furthermore contrary to the common general knowledge of the person skilled in the art, as it is generally known that any material structure will eventually yield to the targeted application of sufficient force.

In T 1431/06, the board held the skilled person directly and unambiguously derived from the description of the patent as granted that, in claim 1, the term “cannot” is to be understood in the context of the normal use of the tube coupling, in which the cap cannot be unscrewed.

It can be agreed with the present board that patent claims must be interpreted through the eyes of the person skilled in the art. This does indeed includes taking account of the skilled person’s common general knowledge. But common general knowledge cannot be derived from patent documents.

However, taking the description as pretext to give an interpretation in flagrant contradiction to what is directly and unambiguously claimed and originally disclosed, i.e. both alternatives, or in other words, claiming that permanently is only relative is going a trifle too far.

The present decision does thus not appear to be correct.

Questions for a referral

The questions for the referral were much too directed to the actual case and it was easy for the board to dismiss the request for referral.

The fundamental question of law which should be decided by the EBA is whether recourse to the description under Art 69(1) and Art 1 of the Protocol has to be systematic or not, or only when dealing with Art 123(3) or in case of lack of clarity of the claims.

In defending its position against the referral, the board referred to T 1473/19. In this respect it can be said that the board was at the same time judge and party.

https://new.epo.org/en/boards-of-appeal/decisions/t200450eu1.html

Comments

11 replies on “T 450/20 – Interpretation of claims and Art 69(1) – A continuation by the same board of T 1473/19”

Calling upon the EBA to clarify a question is a risky business. One might end up with an unfortunate answer.

In claim construction, a judicious degree of wiggle room is in the interests of justice.

For sure, the present case is not a suitable vehicle for taking an open question to the EBA. Adjectives in claim 1 are nearly always problematic. This I learned in the first few weeks of joining a UK patent firm as a graduate patent agent trrainee. An adverb like “permanently” is at least as problematic.

Given that D4 is perfectly capable of removing a thrombus in exactly the same way as the claimed device seems to me to be dispositive of the novelty enquiry. How much more “permanent” than that must the attachment be, for goodness’ sake? Nothing is “permanent” in an absolute sense. Adjectives in patent claims should be given a “purposive” construction: the element should be X-ey enough (bendy enough, long-lasting enough, hard enough, squashy enough) to deliver the function decreed for it in the claim.

Daniel, is there within the EPO any recognition of the usefulness of the age-old English notion of “purposive construction”. What more do the Boards need?

Dear Max Drei,

Thanks for your comments.

I can agree with you that calling upon the EBA to clarify a question is a risky business. It first depends from the way the questions are formulated, but also whether the EBA will rewrite the questions should it wish to give a specific answer. This has happened too often in the recent history and we all know the famous “dynamic interpretation”.

independently of the present case, we nevertheless have two lines of case law which are clearly diverging. One requires the systematic application of Art 69(1) and Art 1 of the Protocol when deciding upon a claim and the other one only in exceptional situations or when deciding upon the requirements of Art 123(2).

I agree with you that relative terms or adjectives in a claim are to be avoided as much as possible.

In the present case the terms “permanently attached” have, in spite of a possible vagueness, which I would deny, a very specific purpose. It is to re-establish the blood flow while pushing the device through the blockage, whereas in D4 the device acts like a stent and pushes the blockage aside when the stent is expanded.

It might well be that for the period of time in which the stent is pushed through in D4, we a have a similar configuration in the patent and in D4. The notion of ex-post facto analysis does not apply for N, but without the previous knowledge of the patent, it was not directly and unambiguously derivable that D4 and the patent were identical. The technical information conveyed in the patent and in D4 remain quite different.

When looking at the disclosure as a whole, there is no room to consider that being “permanently attached” can mean that the permanent attachment is actually releasable. The subject-matter of D4 is a stent which stays in place, hence the need to have a releasable connection. This is however not the case in the patent at stake.

Using the English notion of “purposive construction” (Greetings to Catnic), no different conclusion can be reached.

The boards have always been reluctant to adopt national case law. I would go as far as to claim that coming from a country with common law, it is not at all palatable. To my knowledge, the only national case law which has been adopted by the boards were the “Swiss type” claims. With the amendment of the EPC in 2000, they are now even forbidden.

On the other hand, I also know that Catnic has been severely criticised.

See for instance: http://www.jonathanturner.com/Catnic.htm

Daniel, thanks for the Link to the article from J Turner QC, critical of the Catnic approach to claim interpretation.

As to “permanently” attached, I was prompted by F Hagel to look at D4 and was immediately struck by the similarity of D4 Fig and Fig 1 of the patent here in suit. If you needed to remove a thrombus but the only tool you had to hand was a D4 device, you could use it, right? In particular, its connection is permanent enough for you to use it successfully. Deploy part of the length of its stent, squash the thrombus, then pull the partly deployed stent back into its catheter sleeve.

It would be different, of course, if the D$ device has a push wire 7 that is only able to push the stent cage out of the end of the catheter but has zero capability to pull a half-deployed stent back into the catheter sleeve. But for safety reasons, the likelihood is that the D4 device allows the operator a change of mind and the chance to pull a partly deployed stent back into the catheter.

Next, I looked at Figs 10 and 11 of the patent in suit and its paragraph [0028] describing how you can release the metal mesh device 1 from the push wire 7 and leave it in place in the bodily lumen (just like a stent). What????? Am I missing something? Or did the ED miss something, in failing to ask Applicant EITHER to remove from the specification Figs 10 and 11 and para 0028 OR to add wording to state that Figs 10 and 11 are NOT the “permanently” invention?

Dear Mr Thomas, dear MaxDrei,

The patent at hand offers a highly unusual occurrence : it cites one and the same prior art (D4) in two parts (para 0002 and 0014), but under different numbers (US2005/209678 and US7300458).

Looking at para 0014, it is not surprising that you disagree about the novelty over D4, as para 0014 seems to blur the distinction between a device to restore blood flow in a vessel and an implant or stent.

As to the Board’s position that Art 69 refers to the description of the patent as granted and not to the application as filed, it is indeed supported by the literal wording of Art 69. But it is my view that it is not consistent with the general principle that the relevant date for the skilled person and the common general knowledge referred to in the application of the EPC conditions (explicitly for Art 83 and 56, implicitly for Art 54 and 123(2)) is the filing date. For consistency, the skilled person to be considered in the interpretation of claims under Art 69, because its definition refers to the filing date, should look at the description of the original application rather than at the description of the patent as granted.

This has become an issue since the EPO has set about to impose substantive amendments to the description. I doubt that such a practice was ever contemplated in the drafting of Art 69 and its legislative history.

It is also of note that substantive amendments to the description may raise a new matter issue just because they alter the interpretation of the claims by the skilled person in the opinion of a court.

That argument is really creative to get rid of the need to amend the description. Not an easy one to dismiss either.

@Wai

On the question of whether pre-grant amendments of the description raise a new matter issue, the UK MPP Section 76 (see excerpts below) makes it clear that pre-grant amendments may be held new matter by a UK court if they alter the interpretation of the claims by the skilled person.

This suggests that applicants could resist a requirement by the ED that they enter a substantive amendment to the description, or challenge an amendment entered by the ED as part of the Rule 71(3) notification, by arguing that the required amendment would alter the interpretation of the claims and violate Art 123(2), and put the granted patent at risk of revocation in opposition or court proceedings.

The idea would be to shift the onus of proof to the ED, which in my view would be entirely legitimate. The risk of revocation is far from theoretical, the unfortunate decision T 1473/19 issued by the same Board and referred to several times in the decision provides a striking illustration of such an iatrogenic revocation (addition of a clause in claim 1 by the ED considered new matter because of a missing comma).

Section 76: Amendments of applications and patents not to include added matter

Sections (76.01 – 76.28) last updated: October 2021.

76.06 When considering in Bonzel and Schneider (Europe) AG v Intervention Ltd [1991] RPC 553 whether an amendment to the description had the result that a patent as granted disclosed matter which extended beyond that disclosed in the application, Aldous J described his task as

(1) to ascertain through the eyes of the skilled addressee what is disclosed, both explicitly and implicitly in the application;

(2) to do the same in respect of the patent as granted;

(3) to compare the two disclosures and decide whether any subject matter relevant to the invention has been added whether by deletion or addition. The comparison is strict in the sense that subject matter will be added unless such matter is clearly and unambiguously disclosed in the application either explicitly or implicitly.

As summarised by Jacob J. in Richardson-Vicks Inc.’s Patent [1995] RPC 568, “the test of added matter is whether a skilled man would, upon looking at the amended specification, learn anything about the invention which he could not learn from the unamended specification.”

76.07 In the Bonzel case, it was decided that additional matter was disclosed by an amendment resulting in a guide wire lumen of a dilatation catheter being described as “relatively short” (compared with the prior art), rather than as “about as long as the (catheter) balloon” (the original description of its length). The terms of the comparison at (3) above conform broadly with those of the test for novelty adopted in some EPO decisions as a basis for determining the allowability of amendments. (i.e. no (new) subject matter may be disclosed by amendment which is not derivable directly and unambiguously from the original application by a person skilled in the art; see, eg, Technical Board of Appeal Decision T201/83, OJEPO 10/84.) However, in A C Edwards Ltd v Acme Signs & Displays Ltd [1990] RPC 621 at p.644 whilst acknowledging that the novelty test could often prove useful, and would have given the same result in that case, Aldous J observed nonetheless that it should be applied with caution.

76.14 There may be no objection to an amendment introducing information regarding prior art, provided it does not alter the construction of the claims of the patent in suit (Cartonneries de Thulin SA v CTP White Knight Ltd [2001] RPC 6).

Francis, you might be interested – if you’ve not seen it – in the decision of the English Patents Court in Ensygnia v Shell [2023] EWHC 1495 (Pat): https://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/Patents/2023/1495.html

There is an extensive discussion here with regard to the effects of marking certain embodiments as being “outside the scope of the claims”. One of those effects is a finding of added matter (see [167]-[188]); there is also a finding of extension of protection (analogous to Art 123(3) EPC) (see [189]-[201]).

Based on my reading, the issues there arose from post-grant amendments to the specification (the “C” specification) rather than from amendments made prior to grant (the “B” specification), but there does not seem to be any reason why – as a general rule in other cases – the same principles might affect claim interpretation in light of the “B” vs. “A” specifications.

Note also that the general issue of claim construction in light of “disclaimed” subject-matter in the specification was discussed at [117]-[120].

To my mind, this decision illustrates the logical fallacy of Mr Thomas and his supporters when they argue that making amendments to the specification does not, in any way, constrain national courts post grant (indeed, if that were genuinely the case, why does the EPO make such a fuss about needing applicants to make such – allegedly pointless – amendments?). Here we have a case where description amendments had a direct impact on the Court’s understanding of the case.

Whether or not the EPO actively seeks to tie the hands of national courts, it seems that this is nevertheless a de facto outcome of its practice.

Correcting a typo above: when I said

“there does not seem to be any reason why – as a general rule in other cases – the same principles might affect claim interpretation in light of the “B” vs. “A” specifications”

I meant:

“there does not seem to be any reason why – as a general rule in other cases – the same principles WOULD NOT affect claim interpretation in light of the “B” vs. “A” specifications.”

In other words – to be totally clear – the principles in this case seem equally applicable to description amendments upon grant at the EPO, as they are to post-grant amendments in national proceedings. In either case, the content of the description is modified relative to an earlier version, with the potential to influence the claim interpretation.

@Anonymous

Many thanks for the information regarding this decision. The patent at issue is a UK national patent but the discussion of claim interpretation esp. at [117] does refer to Art 69 EPC as an overarching principle and has general value. The risk of new matter arising from description amendments requested by the EPO is quite real.

There can be no doubt that the EPO’s objective of its practice of description adaptation is to tie the hand of national courts. See in a press release of July 7, 2021 « EPO practice confirmed on adaptation of the description » :

“ Diverging interpretations of the scope of the claims can be avoided if inconsistent information contained in the description or drawings is already removed in the proceedings before the EPO. Thus, the support requirement of Article 84 EPC also serves the aim of ensuring legal certainty for national post-grant proceedings.”

The EPO practice has already had broader negative implications with the divide between BOAs over the application of Art 69 to the interpretation of claims during examination and the reliance in Art 69 on the description of the granted patent as opposed to the original application as we can see on T 450/20.

There is now breaking news on this topic !!

In case T 0056/21 (EP3094468), BOA 3.3.04, known for having voiced well-reasoned opposition to the EPO practice in T 1998/18, suggested in a communication of July 21 to refer the following questions to the EBA :

“Is there a lack of clarity of a claim or a lack of support of a claim by the description within the meaning of Article 84 EPC if a part of the disclosure of the invention in the description and/or drawings of an application (e.g. an embodiment of the invention, an example or a claim-like clause) is not encompassed by the subject-matter for which protection is sought (“inconsistency in scope between the description and/or drawings and the claims”) and can an application consequently be refused based on Article 84 EPC if the applicant does not remove the inconsistency in scope between the description and/or drawings and the claims by way of amendment of the description (“adaptation of the description”)?”

The appealed decision is a rejection of the application after the applicant has refused to adapt the description as required by the ED. The BOA’s communication is only a suggestion but given the context, the applicant will likely agree.

Dear Mr Hagel,

Thanks for your comments.

It should not come as surprise that Art 69 applies to the patent as granted and not to the application as filed. The examination procedure ends up with a fiction as its result is actually to establish the patent as it should have been originally filed.

The problem is that in matters of application of Art 69 in procedures before the EPO we have two diverging lines of case law.

Some boards want a systematic recourse to the description with the possibility to always interpret the claims, even when it comes to Art 123(2), e.g. T 1473/19, T 1167/13 or T 2773/18. All those decisions go back to T 16/87.

Other boards want to limit the recourse to the description to very specific situations, one of those being the application of Art 123(3). This line of case law is exemplified by T 169/20, T 821/20, T169/20, T 1127/16 or T 30/17. All those decisions all go back to T 1279/04.

To me this problem should be dealt with first.

There are also big divergences in procedural matters between the boards. Those divergences should also be clarified as it has become too much dependent on the board which will deal with a case, which line of procedure will be followed.

To all other commenters,

The topic of the present blog was never about amendment of the description. My position in this matter is well known and I will thus refrain to comment in substance to the corresponding comments.

It suffices to say that the requirement of adaptation of the description is enshrined in Art 84 which does not only deal with clarity as such but also with support of claims by the description.

As long as Art 84 is at it is, adaptation of the description will have to be carried out. That this should be done carefully and not in a pedantic way goes without saying.

The last comment reminds me actually of the situation with reference signs in the claims in the early days of the EPO.

A UK court had considered that reference signs would be limiting, and UK applicants, or at least a large one, systematically deleted reference signs at grant.

I doubt the EBA will be impressed by such a national decision about the adaptation of the description.